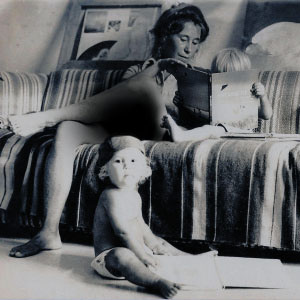

My mother’s voice is rich, velvety, and soft as the skin thinning across her knuckles. As a child she read every day to me and my two brothers who bookend me by two years each. There is a photograph my father took of me, a bare-chested toddler, hair turned white as corn silk from the Florida sun, and my mother, her rich brown hair piled up; our faces are turned down in tandem to the book on her lap, and my hand is resting on her shoulder. What I remember from those books, read during the day, but in longer duration at night before bed, is vying for a place beside her. I would press my cheek to her shoulder and hear her voice coming up and out of her. I would listen to the breathing patterns that the commas and periods and new paragraphs set.

My mother’s voice is rich, velvety, and soft as the skin thinning across her knuckles. As a child she read every day to me and my two brothers who bookend me by two years each. There is a photograph my father took of me, a bare-chested toddler, hair turned white as corn silk from the Florida sun, and my mother, her rich brown hair piled up; our faces are turned down in tandem to the book on her lap, and my hand is resting on her shoulder. What I remember from those books, read during the day, but in longer duration at night before bed, is vying for a place beside her. I would press my cheek to her shoulder and hear her voice coming up and out of her. I would listen to the breathing patterns that the commas and periods and new paragraphs set.

Beginning when I was five, we did not have a television. My mom would read long chapter books to us: all of Roald Dahl’s titles, Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story, Richard Peck’s series featuring the future-seeing Blossom Culp. We begged for one more chapter and then one more page to continue hearing our mother’s voice. She would transform it—throwing it high or lowering it octaves—to embody each character.

I love being read to, and now, in my capacity as a teacher, I perk up when students read aloud. When visiting writers come to give public readings, I lean forward and listen hard to their words. Sometimes I cannot stop small sounds of pleasure from escaping my mouth. And I read to my children, gathering them into my arms, pressing my face to their bath-fresh cheeks.

Back when I was young, my father would occasionally come in, fold himself to sit on the bottom bunk, and tell us stories amended from what he was reading in his educational PhD program. Once he told us the story of the terrible Grendel from the epic poem Beowulf. It made my tiny legs vibrate with fear, and yet I begged, “More, Dad. Please.” One of my earliest memories is being crouched in the warm, safe, dark of a closet, listening with rapt pleasure to the metallic speed of his electric typewriter. He also had a reel-to-reel recorder, and he would have us speak and tell stories, which he would then replay for us. I remember asking him, verging on the age of three, “Is that me?” as I did not recognize my voice.

At dinner each night, my family told the story of our days. We valued stories in our family, although I appreciated this truth only once I had left home. I hadn’t realized that not everyone spent such a great deal of time with family talking, debating, and full-out arguing. We were encouraged to watch the evening news together, and these often dismal stories of the world and our nation and their impact would be addressed by my father over dinner. His even tone and logical approach worked to soothe my disquieted heart. I was the one who would often well up, my argument interrupted by my tears, unable to coherently communicate.

On Sundays, my mom took us to mass for worship. My father stayed home or went hunting. The woods were his church, he told us. I loved the mystery of the Catholic rituals: the collapsing face of Jesus on the crucifix, the droning hymns, the psalms and refrains. I lived for the gospel and homily. I would press my cheek to my mother’s arm, then as I grew taller, I rested my head on her shoulder. Sometimes we would hold hands. When I was a teenager, this physical connection did not happen as much, and yet looking back, always what comes into focus is my mother, her voice in song or refrain, and there I am, trying to press against that rich faith, that ferocious love. Our priest had a deep, resonant voice that filled the church even without the microphone. Sometimes he would gesture with his large Abraham-Lincoln-like hands.

It was the stories I came for—the continuation, the process, the life of Christ. What would happen next? I knew the ending, of course. Christ was crucified, then he rose from the dead. But each year, it seemed a new story. Each year I was a bit older, and I understood or questioned a bit more. I aligned myself with different characters or saw myself revealed through a passage I thought I couldn’t possibly have heard before. But I had moments, and in these moments, the words, quality of light, and warmth of the church all combined to create an effect. It felt as though my rib cage opened like a birdcage with a door I did not know was there. Tears would stream down my face, and I would feel awash in love, held up by it and filled up by it. If my mother had not been there to hold me, I might have floated off, for I very much wanted to feel this feeling all of the time. The words—in song or psalm or gospel—unlocked something so visceral that I could almost hear the click.

I do not remember learning to read. I remember being very young, maybe four, in our basement apartment in Greeley, Colorado. I was in the kitchen sitting at our small table. My mom was frying homemade French fries. My younger brother was young enough to be in the backpack carrier she shouldered effortlessly. I was tracing my name, written in clean, blocky print on a brown grocery bag that had been cut into squares. Then I wrote my name on my own, gripping the pencil ferociously. I wanted desperately to write, desperately to read. These creative acts seemed magical, mysterious, and sacred. Three decades later, this sense has only grown stronger. To tell stories and use words to find meaning and beauty in one’s life, and to be able to transform the terrible and even traumatic into art by the arrangement of letters: what could be more powerful? Or more divine?

When I was eight, the fifth grade teacher chose me to be the voice of God for a play. I hid behind the altar and spoke my lines with feeling into a tiny microphone that was normally clipped to the priest’s vestments. It did not for a moment seem strange to me that the voice of God sounded like a child (and even then a female child). I thought that God would surely have the voice of my mother on some days and the voice of my father on others. It certainly made me tremble in awe and fear.

In my adult years, while I was working toward my MFA in fiction writing at Purdue University, I lived monastically, away from my husband during the week. All of my energy was given freely to reading and writing and teaching. Writing became a prayerful act in which I fully immersed myself in a solitude I had never experienced before. In my dorm room and small apartments, I felt as though I was in a womb. I felt safely housed and actively becoming as though I was revealing myself through fiction, coming to terms with my many selves, and finding a measure of peace. Years before I had my two children, I labored to know myself through the art of fiction.

I left the Catholic Church for good nearly five years ago. It was painful. There was much to read that made my heart a place of rage. But the final decision came through my process of writing. It was through writing that I could get to what I think and believe. As a woman, a mother, and a writer, I could not stay.

I was adrift. We moved, started new jobs, and found our footing in the town where I grew up. I had never planned to return, but my parents are still here, and they opened their home to us as we sold ours. There was joy—real joy—and my mother allowed me short stretches of quiet I wouldn’t have had otherwise to walk, to journal, to sit out back with a cup of tea. It was in these moments of silence that my relationship with the Divine began. I developed a sense of being in conversation with God—listening attentively, paying attention, and trusting myself. I alternated between feelings of liberation and feelings of fright as I traveled a path with no set structure, agreed-upon vocabulary, or set way to worship.

I learned about Quakers through a book club. I had watched the Quaker character on the HBO show Six Feet Under with some interest, but I knew very little about Friends. I do not remember the book we discussed, but somehow we got on the subject of God, religion, and spirituality. After having had two very good beers, I declared that I believe in the Divine and so do my children and also that I miss having a faith community. Before we moved, I had attended both an Episcopal service led by a female priest and a small Jesuit church in our neighborhood, but had not recently sought a faith community. I was still angry.

A couple of months later, I got an email from a member of the book club who is a Friend. She recalled my searching words and invited me in a graceful and loving way to meeting for worship. I went the very next Sunday. What else to call it but a wordless homecoming? It felt as if I was returning to a place I had missed so very much. I sat in the silence and listened attentively. I was embarrassed when tears came momentarily, but they were tears of gratitude. Now I return each week to the sanctuary of silence to take in the wisdom and the messages of my Friends that speak to the condition of my heart. There I encounter the Divine directly or else fidget and work on settling into that place. This experience is often without words, but sometimes they do come—the welling up of wonder. I bring my whole self to worship.

It has been nearly two years now. My life has been transformed by the honesty of my worship experience with this faith family. We often eat together, sharing a potluck meal after meeting.

We can carry our personal messiness and flaws into worship and be no less loved. I do not go to worship to be fixed; I go to be transformed. In daily life, I try to find 30 minutes of silence each morning before I write. In weekly worship, I sit among my Friends and realize they are more than that—they are people I truly love. They have counseled me, comforted me, and run a marathon-relay with me. They have allowed me to see in action, over and over again, “that which is God” in myself and in others—what a gift.

The dear Friend who first invited me to worship also told me about the gorgeous Quaker tradition of being “held in the Light.” These words were powerful and transformative for me at the time. They were a bridge to forgiveness of self and of others. I’ve come to find holding someone in the Light to be a comforting act which feels nearly tangible as friends and family struggle in sickness and with the pain of loss. It is a wonderful way to give thanks for those we love or are working to love. For most of my life, the heart of my perception of God was judgment. It was a child’s idea that I carried until my early 30s with an internal monologue so harsh I often asked myself, “Do you kiss your mother with that mouth?” Now I feel this love as an unconditional balm on most days, and when I struggle, I place myself in the Light, turn my face toward it, and think, “Here I am.”

And now, I have come to the point where I am crafting my letter requesting membership. How well words have served me all of my life, what joy they have brought me, what consolation and comfort, what direct connection to the Divine they have provided. And yet, now, when I must put into words why I am called to membership, I understand only too well their limitations. How can they express the swelling joy, the deep currents of mystery, and the ways my life has been grounded, supported, and sustained by the tenets of such simple, lovely faith?

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.