So Abraham called the name of that place, “The LORD will provide,” as it is said to this day, “On the mount of the LORD it shall be provided.” —Genesis 22:14

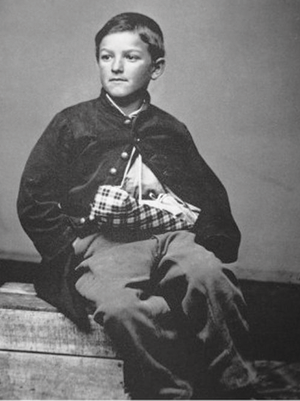

We’re nearing the end of a four-year period marking the 150th anniversary of the Civil War. I’m only three generations removed from that war. My father’s grandfather, brought from Ireland as an infant during the Great Famine, signed up to be in the Union Army when he was 15. He was a drummer boy. It is such a charming image, the willowy lad in his spanking new, blue uniform, sleeves perhaps just a bit too long, pounding away with all the earnest energy of youth. And yet it was an incredibly dangerous job, which is why it was a boy’s job. Particular drumbeats carried over the noise of battle to communicate particular orders. If your drummer got killed, you lost your ability to maneuver coherently under fire, which meant you lost the battle. You’d want a small target, say a boy of 15.

Daniel, my great grandfather, served for almost a year. He was absent from one of the most horrendous battles, Antietam, because he had been on guard duty in Washington, D.C.—keeping watch, so family lore has it, on Belle Boyd, a notorious and beautiful Confederate spy not much older than he, who reached through the bars of her prison cell to nudge him awake. “Son,” she said, “they shoot boys for doing that.” Daniel was present, however, at another appalling battle: Fredericksburg, in December of 1862, where the Irish brigades did the bulk of the fighting and the dying. That night, an aurora borealis, unheard of that far south, spread across the Virginia sky. Both sides took the pulsing, electric green curtains high overhead as a sign that God was on their side.

No one ever goes to war without theology. Violence is natural, just as hunger is natural. As the famine that drove my ancestors to America was political, so war is the result of a culture’s conscious choices about meaning and value. If you teach in a Friends school (as I do) and if your school has the teaching of nonviolence written into its mission statement (as mine does), then you might want to remind yourself (as I need to) that war is a profoundly meaningful and even sacramental experience, willfully chosen and willfully prepared for. Sitting in a classroom decrying the horror of combat is not only too easy, it also misses the point.

One of the most troubling effects of war is the belief we’re forced to develop in its aftermath: that its suffering must not have been for nothing. This effect of war might also be one of its most insidious causes. Nothing as horrible as war can happen without us believing that it’s for the sake of some great good—the greater, the better. Best of all is a good that can’t be exhausted no matter how unspeakable the suffering—a good that reaches into the infinite. Call it God or the gods or Country or Liberty or even just our own sense of deserving to survive in the universe because we happen to be Us and not Them. Our suffering is thereby justified and is perhaps even (and here’s the really troubling part) encouraged. That is, if this infinitely greater good is to be made manifest in this world, it requires of us the costliest sacrifice we can make: our willingness to send our children to die. Only then will we merit divine favor. All our smart bombs and high-tech armaments have done little to alter this ancient need to propitiate the Most High. If anything, our awesome powers of destruction have made us crave the idols of justification all the more. The Civil War, with its sophisticated weaponry, is often called the first modern war. And there in Fredericksburg, my great-grandfather’s Union comrades believed God was with them, a comfort in their staggering loss; the Confederate troops that Daniel faced believed God was with them, a helpmate in their victory. The young who lost their lives were therefore “sacrificed,” a word that literally means “made holy.”

God said to Abraham, take your beloved son, Isaac, and offer him as a sacrifice. Prove to me that you love your God even more than your own son. Isn’t this the perfect metaphor for war? The old killing the young in the name of God. We do a remarkably good job of making that killing meaningful and even pretty: parades, uniforms, somber and prayerful ceremonies, drummer boys who are decorated for their service to the nation. On my desk before me right now is a medal that my great-grandfather received, a brass star tarnished with age and dulled by handling, intricately etched with noble words and god-like figures, and pendant from a frayed stars-and-stripes ribbon. I treasure this medal, and I am profoundly grateful to this 15-year-old young man. I admire his courage, his love of his adopted country, and his willingness to give his life for the sake of others. Jesus says there is no greater love. I never want to forget how lucky I am to be here at all considering what Daniel risked, nor do I want to forget how lucky I am to live in a nation that gets to continue its great experiment in freedom because of sacrifices on the battlefield. But an aspect of the freedom he fought for was my freedom to make choices different from his.

Daniel went to war as a teenager; when I was a teenager, I marched into my draft board and announced that I wanted to register as a conscientious objector. This being shortly after the ceasefire in Vietnam, I was told that CO status was not an option at that time since there was, technically, nothing to object to. Nothing to object to? Saigon fell a few months later, and a small Asian country that 55,000 Americans died defending ceased to exist. Nothing to object to? War is so common in history that we might as well just go ahead and call it history. The students who sit in my classroom are the exception: children who are spared war. The rule is that young people do the fighting and the dying; that’s why it’s called the “infantry.” Jesus may have held up the ideal of laying down one’s own life for others, but he also told a story about a king who was getting ready to go to war; when the king saw that his enemy had many more troops, he decided to negotiate for peace. Jesus is making a point about commitment: you haven’t done it until you know what it will cost you. But he’s also making the same point about war: don’t do it without knowing the cost. And the cost is always the lives of our children.

How does the story of Abraham and Isaac end? God stops him from killing his son. This is one reason I’ve never accepted the notion that Jesus died to save us from our sins, his own Father killing the Son for a divine purpose. My students and I were talking about these issues one day in a world religions class—my students, who are about the same age Daniel was when the aurora lit up the sky over Fredericksburg. One member of the class had a thought about the Isaac narrative that shows the critical thinking that can happen in the classroom of a Friends school. “Yes,” my student said, “God is testing Abraham, but when Abraham says yes to God he fails the test. God gave him every opportunity to stop, right up to the moment the old man lifted his blade to strike. This test wasn’t about proving his faith to God; this was about finding out for himself what faith should and should not do.”

My student’s hypothesis came with some scriptural authority. For one thing, our class noted that little good came from this test: Isaac’s mother dies immediately afterward, and Isaac himself never seems to recover either physical or mental health. For another, our class remembered the passage earlier in Genesis where Abraham barters with God to save Sodom for the sake of ten good people, thus learning a lesson about compassion’s power—and its limits. Why did Abraham not argue similarly for his son? Could it be that in a certain place in his soul where his faith was at its strongest, he wanted to make the sacrifice? It was not that he wanted to kill his son, rather that he wanted to show that his faith had no limit. But everything in human life is limited, including our understanding. So, maybe Abraham was supposed to say no. Maybe he was supposed to discover for himself, as he did when negotiating for Sodom, that he needed to think a little harder about what God really asks of those of us who claim to be faithful. The Lord directed Abraham to a ram caught in a thicket. In providing this other sacrifice, could the Lord be asking all of us to look harder when it comes to the lives of our children?

There’s a brilliant sequence in the first movement of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7, the one he wrote during the siege of Leningrad. As the lush and glorious opening section dies away, a lone snare drum quietly begins pounding out a quick military beat—the kind of thing Daniel would have played. A jaunty little tune comes in, and it’s all lots of fun, suggesting parades and drills and waving flags and easy patriotism. As the tune is developed through a dozen variations, it turns by degrees into a chaotic, horrific, ultimately terrifying mass of sound. It’s hard to believe that this violence all started with that one little figure on the drum. And yet, step by step, that’s what happened. Could it have been otherwise? A final exhausted, ragged repetition of the marching tune at the end of the movement suggests so or at least asks where else this drumbeat might take us. We know what it has led to; what can it lead to?

I am grateful to my great-grandfather for making my life possible. My commitment to nonviolence in no way diminishes that gratitude. How do I live in such a way as to bear witness to that gratitude, both to him and to those who go to war today? I wish I had an easy answer. All I have is more questions. Where else can those drumbeats lead us? Where else but war can we get that profound meaningfulness? When we go up onto those high places where we are called to do the hardest things, will the Lord provide? I’m older now than Daniel was when he died, and the only wisdom I claim is the wisdom of waiting in expectant and hopeful silence. That’s why I teach in a Friends school. It’s a good place to listen, especially during a time of war. Sometimes, if I listen well enough, I hear a young person wonder if we need to say no to God now and then. If I listen even harder, I sometimes believe I hear Daniel’s drum echoing in that refusal—a refusal that just might be the ultimate affirmation.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.