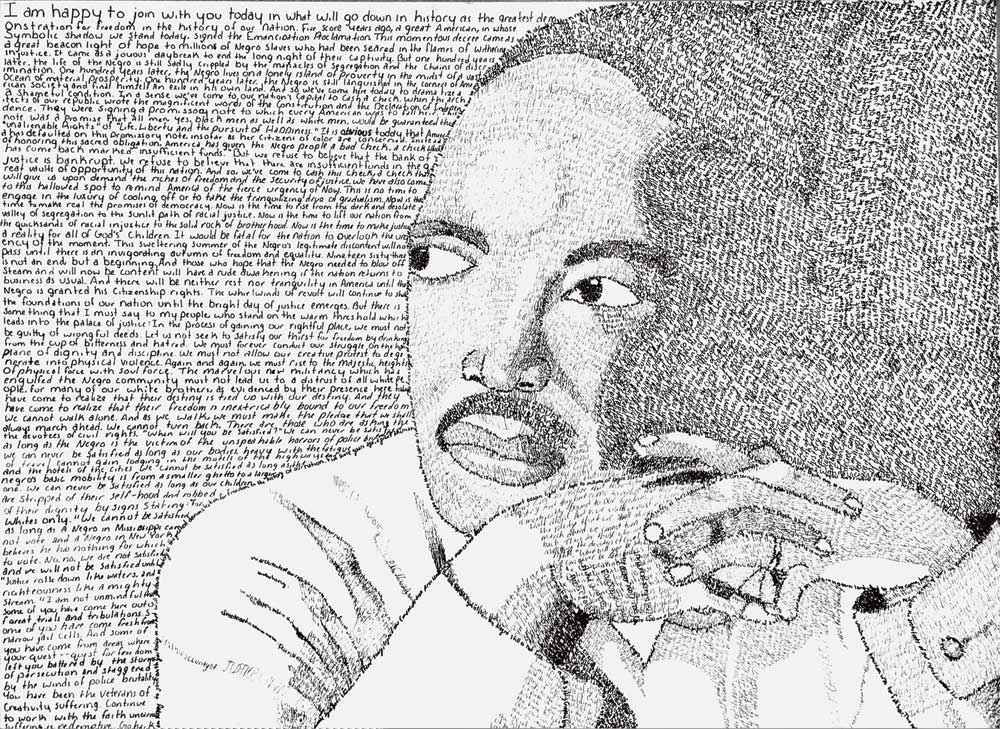

In March, I received an invitation to this summer’s Friends General Conference Gathering in Johnstown, Pa. Pulling the flyer from my mailbox, I was moved to read that the Gathering is going to honor the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1958 keynote address to FGC. I was further inspired that the Gathering is going to focus on how we, as a people of God, are also called to an activism of "courageous faithfulness" like King.

I had to smile, though. Martin Luther King is one of the most powerful examples of faithfulness through social activism—but perhaps not in the way most of us think. It is easy to look back and say King was a man of amazing courage and a born leader of the peace and freedom struggle. Yet, as I often tell my students in the activist training program I direct at Antioch University, King’s journey to social activism is really a testament to the power of "fearful faithfulness." His own story dramatically reveals that one does not have to feel courageous in order to be an effective activist, let alone a faithful follower of Jesus.

Kings’s Fearful Journey to Activism

On December 1, 1955, King was just 26 years old and new to Montgomery, Alabama. He did not know Rosa Parks, and his church was one of the smallest, wealthiest, and most conservative of the two-dozen black churches in town. His ambitions at the time were to run a solid church program, have a nice house for his family, write some theology pieces for his denomination’s magazine, and do a bit of adjunct teaching at a nearby college. King’s long-term career goal was to become a college president someday.

At the time, King never imagined himself as the most prominent activist leader in Montgomery, let alone the United States. He had read some Gandhi and Marx at Boston University and written some papers about the social gospel movement that challenged the Church to take up the fight for social justice. But, that December, all these ideas were "back burner" concerns for King. His only act of overt activism up to this point in his life had been to write a letter to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution against segregation—back when he was 17 years old.

It is hard to imagine now, but if it had been left up to King’s initiative, the Montgomery Bus Boycott would never have happened. The real leader of this effort was E.D. Nixon, an experienced civil rights and labor activist who helped launch the boycott just four days after Rosa Parks’ arrest for refusing to move to the back of the bus. As the president of the Alabama chapter of the NAACP, Nixon knew Parks well. She had worked with him as an NAACP volunteer for over 12 years. He also knew most of the city’s black clergy and almost all of the local black activists, including folks from his union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

When Nixon bailed Parks out of jail, they went to her house to discuss their plan to launch a boycott of the city’s bus system. Nixon then went home and started calling local ministers to line up their support. As Nixon explained later: "I recorded quite a few names. . . . The first man I called was Reverend Ralph Abernathy. He said, ‘Yes, Brother Nixon, I’ll go along. I think it’s a good thing.’ The second person I called was the late Reverend H.H. Hubbard. He said, ‘Yes, I’ll go along with you.’ And then I called Rev. King, who was number three on my list, and he said, ‘Brother Nixon, let me think about it awhile, and call you back.’" When King finally called back, he only agreed to come to a meeting to discuss the boycott idea with the other ministers. Nixon chuckled and told King, "I’m glad you’ve agreed to come, because I already set up the first meeting at your church!"

At the meeting, King was still nervous about the militancy of the boycott proposal—even though it had already been endorsed by the Montgomery Women’s Political Council, which included some members of his own church. Soon, after listening to King, other ministers began to side with him against the boycott idea. In his own memoir of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, King recalls how Nixon finally exploded, slammed down his fist on the table, and shouted that the ministers would have to decide if they were going to act like scared little boys, or if they were going to stand up like grown men and take a strong public stand against the injustice of segregation. Nixon’s outburst hurt King’s pride and he shouted back that nobody could call him a coward. Then, to save face, King agreed to Nixon’s plan for an aggressive boycott campaign. The other ministers soon agreed too.

The group then began to discuss who should lead the effort. Everyone present had expected Nixon to become the president of the newly formed Montgomery Improvement Association. But when he was asked about serving, Nixon answered, "Naw, not unless’n you all don’t accept my man." When asked whom he was nominating, Nixon said, "Martin Luther King." Having just loudly declared his prideful "courage" to the whole group, King felt he had to agree. Nixon then informed King that, as the new president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, he would also have to give the main address at the mass rally scheduled for that very night to announce the boycott plan to Montgomery’s black community.

The Spirit surely works in mysterious ways. While fearful, King rose to Nixon’s challenge—and the Bible’s prophetic call to seek justice and oppose oppression. Serving as the leader of the Montgomery Bus Boycott for the next twelve months also changed King. Watching 42,000 poor and working-class black people stay organized and do without public transportation for a year, he discovered the hidden capacity of ordinary people to resist oppression and move toward freedom together. Watching the conservative, right-wing city government finally cave in to the boycott, he experienced the power of mass nonviolent direct action campaigns to win real victories—even when they are opposed by powerful interests. By seeing his own power to inspire people to become active, faithful citizens for a noble cause, King also discovered what kind of leader he wanted to be. He now embraced his mission as an activist leader.

I tell this story because there are many important lessons in it. We don’t have to be born leaders. We don’t have to attain perfect spiritual wisdom or confidence before we become active. We just have to get started right here, right now—even if we still feel fearful, ambivalent, or doubtful. King’s story is a modern parable. It is an invitation for all of us to take up the cross of fearful faithfulness.

A "Spiritual" Way Out?

In my experience, however, I have seen many Friends harden themselves against the transforming power of fearful faithfulness by finding a "spiritual" justification for ignoring the healing call to help build up the reign of God’s love and justice in our communities. As D. Elton Trueblood wrote, "There have always been those who have so stressed the inner experience that they have, in effect, neglected the work of service in the world." In this, Friends are not alone.

An example of this "spiritual" avoidance of activism can be seen in the anthology called Working for Peace: A Handbook of Practical Psychology and Other Tools edited by Rachel MacNair and several members of Psychologists for Social Responsibility. The handbook’s many chapters, including one written by longtime Philadelphia Friend George Lakey, offer considerable psychological wisdom for anyone "who wants to find better ways to work for peace or otherwise improve the world." Yet, even in this excellent anthology, there is a telling piece of "spiritual" avoidance written by Christina Michaelson, a clinical psychologist who practices and teaches in Syracuse, New York.

Michaelson’s research interests include Eastern psychology, meditation, and inner peace; her essay is called "Cultivating Inner Peace." There is so much that is useful in this essay that we should not ignore. There is no question that Michaelson is, in Martin Luther King’s words, "creatively maladjusted" to the world of violence and imperial war. She lauds all peace activists who "invest tremendous amounts of time, talent, energy, and resources into changing the world." She also claims that this work can be made more effective, and more soul-satisfying, if social activists cultivate their own inner peace through such practices as meditation, nature experiences, counseling, and prayer. I stand with Michaelson on all these points.

Yet, in just Michaelson’s second paragraph, she says something I think we need to question to see if it is well-led. According to Michaelson:

If you’re to bring peace to others, then you must first manifest peace in your own life. Your peace work in the world should begin with cultivating an inner state of peacefulness and then you truly can offer peace to others. Mahatma Gandhi said, "Be the change you want to see in the world." If you want to see peace in the world, then you must "be" peace in the world.

This all sounds pretty good on the surface, and I have heard similar words from many Friends, but if you look closely at Michaelson’s repetitive "first/then" formulations, she is actually counseling would-be peace activists to delay their outward social activism until they have cultivated a deep inner peace and spiritual maturity. She explicitly says it twice and implies it a third time in this one brief passage.

This "spiritual" avoidance of activism is clearly not King’s way or Gandhi’s. As we have seen, King did not wait on either inner peace or spiritual maturity before becoming active in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Instead, King grew in his faith and experienced deep personal transformation in the midst of working with imperfect people, including himself, as part of his fearful, but still faithful, activism building up what he called the "Beloved Community."

I am reminded of a key insight articulated by Jewish activist Paul Rogat Loeb. In his book Soul of a Citizen, Loeb notes how most people, including many people of faith, hold back from becoming activists because they believe that they have to be saints before they can ever begin such work. As he notes:

Many of us have developed what I call the perfect standard: Before we will allow ourselves to take action on an issue, we must be convinced not only that the issue is the world’s most important, but that we have perfect understanding of it, perfect moral consistency in our character, and that we will be able to express our views with perfect eloquence. . . . Whatever the issue, whatever the approach, we never feel we have enough knowledge or standing. If we do speak out, someone might challenge us, might find an error in our thinking or an inconsistency—what they might call hypocrisy—in our lives.

One of the biggest troubles I see with holding back until one meets the perfect standard is that it has never once led to a successful social movement. Time and time again, ordinary people create effective social movements only when they do not wait on sainthood, but just get active—by hook or crook—regardless of whether they feel courageous or embody inner peace. Like Martin Luther King, they just end up surrendering themselves to the power of fearful faithfulness—even if it is partially motivated by insecure pride, or some other form of spiritual immaturity.

To her credit, even Michaelson seems uncomfortable with her perfect standard framework and searches for a more integrated perspective. By the end of the essay, she claims that there are many entry points into social activism and spiritual maturity—which can then feed off each other in creative and reciprocal ways. As Michaelson notes, "Your thoughts, emotions, physical functioning, and behavior are interrelated, and changes in one area affect the other areas in continuous feedback." If more and more of us adopt this second approach of Michaelson’s, I believe Friends will be in a much better position to grow spiritually and respond to the Spirit’s call for faithful social action.

The Way Forward

Here is one more story I tell my students in Antioch University’s Environmental Advocacy and Organizing Program. Back in the 1980s, a coalition of churches, civic groups, and small business leaders organized a campaign in Seattle to honor Martin Luther King’s legacy. Their specific goal was to get their city council to change the name of the main street running through one of Seattle’s predominantly black neighborhoods. They wanted to change the name of this street from the "Empire Way" to the "Martin Luther King, Jr. Way."

After a few months of grassroots lobbying, these folks got the city council to agree. The night after the vote, the neighborhood organizers invited community members to a Baptist church for a victory celebration. That night, theologian and historian Vincent Harding, a longtime associate of King’s, spoke to the community. He urged everyone there to fully embrace the deep symbolism of what they had just accomplished. As he said, "You have just changed the road you travel from the Empire Way to Martin’s way."

Is this not the most profound spiritual challenge we face today—changing the road we travel from the Empire Way to Martin’s Way? Is this not what the Spirit calls all faithful people to do in both large and small ways—even when we feel fearful? Is not activism an essential part of our spiritual practice and faithfulness?

Exactly one year to the day before he was murdered, King gave a public speech finally raising his voice against the U.S. government’s brutal war of aggression against the Vietnamese people. It is important to know that King had opposed the war in his heart for two years, but had been too afraid to speak out against it publicly. Yet, with Coretta Scott King’s support, King did the right and faithful thing on that blessed night on April 4, 1967, at historic Riverside Church on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

King’s words from that day—just as he once again was led into a deep, though fearful, faithfulness—still speak to us:

If we do not act we shall surely be dragged down the long dark and shameful corridors of time reserved for those who possess power without compassion, might without morality, and strength without sight.

Now let us begin. Now let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter—but beautiful—struggle for a new world. . . . Shall we say the odds are too great? Shall we tell [ourselves] the struggle is too hard? . . . Or will there be another message, of longing, of hope, of solidarity with [our own] yearnings, of commitment to the cause, whatever the cost? The choice is ours, and though we might prefer it otherwise we must choose in this crucial moment of human history.

All I can add to this is "Amen."