In his book Why Friends are Friends, Jack Willcuts claims that the first thing to say about us Quakers is that we are Christian. That would not have occurred to me. I have no doubt that thousands of Quakers agree with Friend Jack Willcuts. These Friends identify themselves with the Christian tradition as opposed to other religious traditions, they accept some or most of the core beliefs spelled out in the Christians creeds, and they may believe that pastors have a special relation to God. But nothing revealed in the Light given to me leads me to such a sectarian identity.

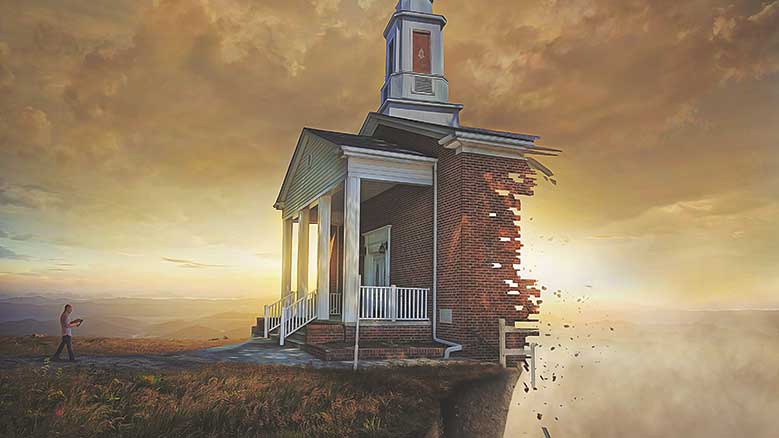

When I ask myself whether I am Christian or not, I do so with an eye on what is studied as Christianity in universities and seminaries, not in the loose sense in which we sometimes say that an act was (or was not) "very Christian." In this sense Christianity: 1) is a religious institution dating back to about the third century CE, complete with ecclesiastical hierarchy and programs such as the Crusades and the Inquisition, 2) insists on and propagates distinctive beliefs about God, Jesus, salvation, and so forth (the "Creed"), 3)regards the Bible (Old and New Testaments) as holy, as the word of God, and 4) stands in opposition to other religious institutions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, paganism, and Islam. My sense of why I identify myself as a Quaker does not rely on any of these four distinctive features of Christianity.

Quakerism was indeed born in a Christian culture. George Fox was raised in a Christian home, he traveled among Christians, he sought out Christian leaders, and he disputed with them about Christian beliefs. None of what he heard struck him as the Truth. It was Jesus, not Christianity, that spoke to his condition. The truth that was opened to him is that Jesus is with us here and now in this eternal present, to teach his people himself. This opening, together with others that fleshed it out in the next year or so, led to a religion that, to my mind, rejects all four of the hallmarks of historical Christianity.

Some think it weirdly mysterious that a person from the past can speak to us in the present, but it happens all the time with parents, siblings, friends, people we have admired or respected, and even fictional characters. Perhaps there is a bit of mystery, but such "speaking" is certainly part of our rich human experience. In this respect, the Jesus that George Fox knew remains human, not some utterly distinct creature, God’s only begotten son. Jesus was, like some other humans, anointed by the Spirit, but his story loses its power and appeal if he was not really human. To my mind the insistence on the utter uniqueness of Jesus is one of the most distasteful and debilitating aspects of the Christian creed.

George Fox studied the Scriptures carefully and consulted them often. My own experience is that this is a valuable practice, which (like many other liberal Friends) I neglect more than is wise or healthy. The Gospels are particularly inspired. The histories, stories, hymns, proverbs, and parables reward study and contemplation. While the inspiration often seems divine, the writing is clearly human. Some stories seem more political or nationalistic than religious, while others, like the parables, require a lot of work to understand. Certainly the Bible we know in English is a human work, since it is not in the language in which it was originally written. Even in the original languages the text was at best human attempts to express the word of God. Elias Hicks may have exaggerated when he wrote that the Bible may well have done fourfold more harm than good, but I like his refusal to idolize the text.

So I doubt that it is correct to call George Fox a Christian. He listened to Jesus, not to the Christian tradition. In this context it is well to remember that Jesus was a Jew, not a Christian.

Christianity as an institution has been a source of violence and oppression, while the life and parables of Jesus model peace and equality. The liberating appeal of Jesus could never be entirely suppressed by the churches, and there are therefore inspiring writings of Christian theologians and ecclesiastics. But such inspiration is not exclusively Christian. I find myself often more in accord with Sufi Muslims, or Jewish writers such as Martin Buber and Abraham Heschel, or the fourfold way of Buddha, than with dogmatic Christians. When I read John Bunyan’s criticism of George Fox and other early Quakers, I admire his civil tone (more civil by far that the responses of Friend Edward Burrough) but am put off by the rigidity of the dogma and his exclusion of the Inner Light. George Fox had a powerful and engaging sense of spiritual reality, but (unlike Bunyan’s) it depended on experience rather than on theology.

No one need be a Realist in order to accept the hard reality of matter, no one need be a Christian to accept the presence of the Inward Teacher, and no one need be a theologian in order to accept guidance from God. I find that religious experience and fellowship regularly trump theoretical consistency and coherence.

I grew up in a Christian not a Quaker home. A. J. Muste, Bayard Rustin, and George Houser introduced me to the poverty of violence and the need for steadfast models of nonviolent alternatives. When I was sent to prison for refusing to register for the 1948 draft, the warmth and admiration of Quakers in Swarthmore and Philadelphia made me feel part of the Quaker fold. It did not matter that I was going to prison alone; fellowship in spirit took away the loneliness. I have felt a Quaker ever since, and have come to a deeper understanding through learning more about the history and traditions of Friends, and about individual Friends, as well as though working with Friends in NYYM and elsewhere.

Just as I went to prison alone without feeling lonely, I know that my thoughts will not be shared in every detail by other Friends. Just as we each lead our own lives, so we each cobble together our own thoughts—in both cases using light from others together with light from the Inward Teacher. Spiritual fellowship does not depend on our having identical ideas any more than it depends on our having identical lives. So my not being Christian does not isolate me from Quaker fellowship.