I remember one Thursday morning at Swarthmore College, probably in the fall of 1949, when the weekly “Collection,” a secularized vestige of what had once been compulsory mid-week worship, hosted Bayard Rustin as the speaker. He spoke about the Journey of Reconciliation of 1947, the model for the better known Freedom Rides of the next decades. It was a gripping story, and shows Rustin in a light that his biographers often miss.

|

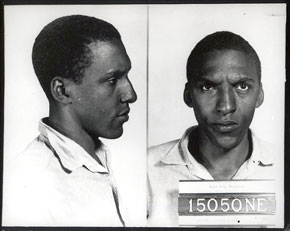

| Bayard Rustin after an arrest |

The background was the U.S. Supreme Court decision of June 3, 1946 (Irene Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia), which established segregation in interstate travel as unconstitutional. Instead of relying on the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Ammendment, as civil rights cases usually do, the Court ruled that state segregation laws were an undue burden on interstate commerce, violating Article VIII, the Commerce Clause of the Constitution. Whatever the reasoning, the ruling was welcomed by the newly invigorated civil rights movement. However, at the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), still at that time an integrated organization), there was a wrenching concern. Leaders such as A. J. Muste, Bayard Rustin, George Houser, Jim Peck, and Wally and Juanita Nelson realized that there were bound to be confrontations in which people seated in ways prohibited by the old state laws would be harassed, beaten, and arrested. These seasoned veterans of direct action knew better than most people how to absorb unjust violence without either a cowardly or a violent response. And they were good at publicity. So they organized the Journey of Reconciliation, forerunner of the Freedom Rides of the 1960s.

The Journey of Reconciliation took place on buses, with each person buying a round-trip interstate ticket through Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and back. They were indeed beaten and arrested, sometimes with inarticulate rage and sometimes with the specious (and later invalidated) argument that the Supreme Court ruling did not apply to a bus that did not itself cross a state line, no matter what kind of ticket the passenger had. Rustin’s speech and manner at the Collection were riveting as he told the story in graphic detail.

|

|

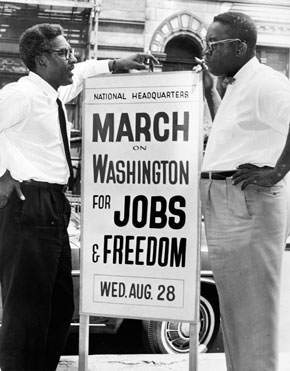

Rustin speaks with (left to right) Carolyn Carter, Cecil Carter, Kurt Levister, and Kathy Ross before a demonstration, 1964 Wikimedia Commons |

The high point of the confrontations came in North Carolina, where they were all sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang for violating state segregation laws. They chose to serve the sentences rather than post bail pending appeal. Rustin decided it would be a good chance to try a little exercise. He picked out the man who seemed the toughest and most hostile among the guards and “tried what love might do.” He was consistently cheerful and polite, he submitted to all the indignities without losing his composure, he always had a friendly greeting, he asked about the guard’s health, he listened to his troubles, and he inquired about his wife and children. It was a slow process, and at first there seemed to be no change at all. But Rustin recounted that at his release after five weeks, the guard came over, “shook my black hand,” and said, “It has been nice to know you mister Rustin.” Quite a breakthrough!

When he finished this tale of heroic nonviolence, Rustin turned to Dean Susan Cobb, who was presiding in the absence of President Nason, and asked whether, since Collection in its historical origins was a religious occasion, it might be appropriate for him to close with a spiritual. She nodded, and in his clear powerful tenor voice he sang “Standing in the Need of Prayer.” A hero telling his heroic exploits, and then standing in the need of prayer. We were all hushed and overcome. You could have heard a pin drop.

|

| March on Washington leaders Bayard Rustin (left) and Cleveland Robinson, 1963 |

It happened, I remember, that in spite of the alphabetical seating, I ending up sitting next to Joe Charny, whose mild Marxist outlook did not have room for a person’s social attitudes being changed by love and whose combative intellect made him eager to argue. As we left he muttered to me, “That wasn’t fair!” Charny’s comment strikes me as very much in the spirit of tough academic scrutiny, at which Swarthmore excels. Religious witness and academic scrutiny belong to different categories. Bayard Rustin was capable of entering either arena, but by ending with a spiritual he put his presentation that morning decisively into the religious category, thereby excluding questions and debate. In an academic arena, that is unfair.

But is it not equally unfair to wrench a religious testimony out of its proper context into the academic arena? Bayard Rustin, raised as a Quaker by his grandmother, was at the time a member of 15th Street Meeting in New York City, and though his attendance later dropped off, I believe he remained a member throughout his life. What most of his biographers have not recognized is that he had deep spiritual grounding, with religious as well as worldly wisdom. That is one thing that emerged clearly in this talk, as well as in his William Penn lecture in the spring of 1948, “In Apprehension How Like a God,” which is mentioned in neither major biography and is omitted from the collection of Rustin’s writings. Bayard Rustin’s spiritual depth has been widely overlooked and deserves to be brought back to our attention.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.