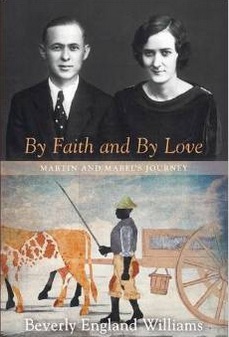

By Faith and By Love: Martin and Mabel’s Journey

Reviewed by Beth Taylor

June 1, 2015

By Beverly England Williams. Resource Publications, 2014. 177 pages. $23/paperback; $9.99/eBook.

By Beverly England Williams. Resource Publications, 2014. 177 pages. $23/paperback; $9.99/eBook.

Buy on FJ Amazon Store

The story of Martin and Mabel England is a riveting contribution to biographies of “the greatest generation.” Born poor in the South in the first decade of the twentieth century, they met at a YMCA conference and became a missionary couple, serving in Burma before and after World War II, and in the United States as diplomats for peace and racial integration until their deaths in the 1980s.

Martin’s passion for racial justice began with the tale of his grandfather, saved from death by an elderly slave who had just bought his freedom during the Civil War. When the old man found the dying soldier, he lifted him onto his wagon, took him to a river to bathe his wounds, and carried the young man back home to his surprised wife. The memory of this kindness that transcended the divisions of race was passed down generation to generation in Martin’s family, spurring a commitment to activism.

Trained as a minister and sponsored by the Baptists, Martin always felt kindred with Quakers, believing that the teachings of Christ led logically to pacifism as well as racial equality. Mabel was always at his side, teaching in classrooms, nursing the sick, delivering clothing and supplies, even as she raised four children.

In Burma in the 1930s, high in the mountains near China, they set up camp, guiding the construction of schools and health clinics—which later, during the war, would be bombed by American planes targeting Japanese troops.

While the war lasted, Martin and Mabel came back to the States and founded Koinonia Farm in Americus, Ga., an integrated agricultural teaching community. It set the tone for their modus operandi. As Martin reported, “One of our neighbors almost threatened me physically when he walked in one Sunday evening and saw we were all, black and white, sitting around our kitchen table, two of the farm workers and my family. Well they were part of my family too.” Years later, Jimmy Carter would cite Koinonia as the inspiration for Habitat for Humanity.

After World War II, Martin and Mabel returned to Burma to rebuild the schools and clinics, taking their growing children with them into the villages, sometimes sending them to boarding schools in India so they could live more safely. Seeing the devastation wrought by bombs cemented Martin’s determination to work for peace and nonviolent resolutions as well as racial integration. But he was realistic about the limits of good will, as he wrote years later:

Looking back . . . I can see that it is not enough to organize churches and send preachers into opium-ridden, hookworm-infested villages where I had worked helping thousands of students have a chance to learn. . . .

For hungry neighbors in Burma I studied agriculture and brought in improved seeds and plants, purebred pigs and a healthier breed of chickens. I tried to encourage schoolchildren to eat carrots. We Americans sent fine young men to wipe out the fields, and the orchards, and the pigs and cattle. On one bombing raid, one American was able to destroy more than a farmer in Burma could replant in a lifetime. It is not enough to plant, to build. We need to try to persuade people to give up their faith in the killing business. While we can never reach even the fringe of this goal, we must keep our face toward it.

When they returned to the United States in the 1950s, Martin and Mabel served in various capacities as lecturers, teachers, advisors, and mentors. One of Martin England’s jobs was to minister to Baptist ministers in need and crisis, including a young Martin Luther King. England finally convinced King, with the help of Ralph Abernathy, to buy insurance to care for his family if anyone followed through on the constant death threats. Representing the Baptists, concerned for King’s safety, England was assigned to visit him in jail and walk with him in the Selma march. It was to England that King handed his first draft of the famous letter from Birmingham jail, allowing it to be printed by the American Baptists as a pamphlet, which then was picked up by magazines for national dissemination.

The gift of this biography is its specificity—the details of racism or acts of bravery; comments of prejudice or faith; ways of living on what one plants, tends, or borrows; experiments in cooperative living and medicine; traveling on foot, by bicycle, in an old, rattling plane or VW; vistas of South Asian mountains, rutted roads, and jungles; translations of languages; dishes of banana, rice, and curry; children’s homeschooled lessons, harsh discipline in classrooms; and conversations between strangers about difficult subjects, using words trying to heal.

The author, Martin and Mabel’s daughter, Beverly England Williams, quotes from their love letters; letters home to their parents; American Baptist archives; a scholar’s oral history; and interviews with her siblings and their parents’ peers and admirers; as well as tributes by the NAACP and schools attended by Martin and Mabel.

Written in lively prose, weaving primary texts seamlessly with Williams’s engaging narrative voice, this story reads well and should be in any collection of twentieth-century histories focusing on the history of nonviolent activism and racial integration.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.