In 1989 I decided to test my faith commitment and a newly awakened interest in spirituality. Following a needed break from my involvement in a liberal Protestant church, I traveled to Italy, one of the cradles of Christianity and Western culture, in spite of wars and terrorist threats brewing in Europe and North Africa that discouraged transatlantic travel. I struggled with the temptation to cancel my flight at the last minute, but an inexplicable inner motion of the spirit convinced me that the potential broadening of personal experience would be worth the risk. It is this continuing inward journey through clouds of uncertainty that has left the most enduring impression on me.

In 1989 I decided to test my faith commitment and a newly awakened interest in spirituality. Following a needed break from my involvement in a liberal Protestant church, I traveled to Italy, one of the cradles of Christianity and Western culture, in spite of wars and terrorist threats brewing in Europe and North Africa that discouraged transatlantic travel. I struggled with the temptation to cancel my flight at the last minute, but an inexplicable inner motion of the spirit convinced me that the potential broadening of personal experience would be worth the risk. It is this continuing inward journey through clouds of uncertainty that has left the most enduring impression on me.

What, then, do I make of the recurring questions and intervals of darkness in such memories? Perhaps it was the sudden twinge of fear for my survival mid-flight over the Atlantic that made me feel I was entering an uncharted region from which I might never return. That fear gave rise to doubt about the real purpose of my trip into the unknown, whether it truly represented a renewal of faith. Perhaps I was simply running away from unresolved disappointments or responsibilities back home. Only after my safe return and much reflection did the meaning of my experience begin to become clear. The element of risk certainly strengthened my resolve to find meaningful openings for understanding and, ultimately, for expressing my faith through service to others.

Early Quaker preacher John Woolman, as we encounter him in his Journal (published two years after his death in 1774), was an explorer of unknown regions of the land and of the heart whenever and wherever he was moved to travel with a particular concern. On one of his trips to the frontier outposts in 1763, he took shelter in his tent from the rain, forced by circumstances to wonder why he felt compelled to make such a hazardous journey in the first place. “Love was the first motion,” he wrote, “and then a concern arose to spend some time with the Indians, that I might feel and understand their life, and the Spirit they live in.” Woolman was no accidental tourist motivated by curiosity or by the spirit of adventure, nor did he see his mission as part of the westward expansion promoted by many of his contemporaries.

A journey to the frontier was a radical step into the unknown. Explorers, traders, missionaries, and settlers needed only to focus on concrete objectives, but for a spiritual pilgrim, as Woolman seems to have been, frontier travel took the form of a faith journey that sought knowledge of what lay within as much as what lay beyond the horizon of contemporary knowledge and experience. In any case, he needed to travel lightly. Friends, family, and many possessions would have to be left behind. Even preconceived notions of the people who lived beyond the frontier needed to be set aside so he could empathize with their experience and find a way to help his own people co-exist with them in peace. In many ways, my own journey to Italy visiting special places of pilgrimage like Rome, Assisi, Florence, and Vatican City revealed to me we’re all in the company of thousands of seekers risking personal safety and separation to pursue a spiritual journey.

Perhaps the most transformative journey in my life began when I was invited by a group of Quakers to be a volunteer chaplaincy visitor at a local jail. I explored this path once or twice a week for almost 20 years until the institution was officially closed down. In this dispiriting environment, where inmates, staff, and visitors alike appear to be groping in the darkness for meaning, I was no different from anyone else. After being allowed access to corridors flanking the ranges of cells, I often felt my resolve weakening, my self-doubt devolving into uncertainty. But then some of the inmates, sensing my hesitation, would guide me along with words of encouragement: “You’re safe here with us, Keith. This is a jail you know!” Whenever I began to lose sight of a clear spiritual or social mandate for being there, some of the same inmates would shine a light on my path. For example, once when I was trying to avoid the persistent demands of one particular inmate, he challenged my excuses with words, “Go with me the extra mile, man. That’s what you’re here for, isn’t it?”

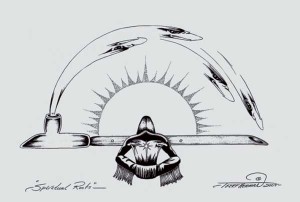

By letting go of my uncertainties and focusing on the practical needs of the prisoners, I was able to assure some that I was making a sincere effort to understand their condition. One aboriginal artist expressed his gratitude by presenting me with a remarkable image he drew that depicts a man with his back turned (perhaps a sign of cultural modesty to avoid direct eye contact) facing into a rising sun. It reminds me of the tree paintings that Woolman observed on his journey, providing him with insights into sufferings, spiritual trials, and revelations of Native peoples that he could begin to relate to.

What does this have to do with journeys into other places of unknowing? For Woolman, “love was the first motion.” Whether or not he was aware of the medieval European classic The Cloud of Unknowing, words from that mystical guidebook may have spoken to his condition: “step above [the cloud] stoutly but deftly, with a devout and delightful stirring of love, and struggle to pierce that darkness above you; and beat on that thick cloud of unknowing with a sharp dart of longing love, and not give up, whatever happens.”

As I find myself growing older and reminiscing on some of the risks that may seem the privilege or follies of youth, I find William Butler Yeats, the Irish poet who wrote “An Acre of Grass,” to be in sync with Woolman, my fellow travelers on the flight to Italy, the prisoners who guided me through the jail, and others who have helped me to penetrate clouds of unknowing. In the light of personal experience, I can happily join in his refrain:

Grant me an old man’s frenzy,

Myself I must remake

Till I am Timon and Lear

Or that William Blake

Who beat upon the wall

Till Truth obeyed his call;A mind Michael Angelo knew

That can pierce the clouds;

Or inspired by frenzy

Shake the dead in their shrouds;

Forgotten else by mankind,

An old man’s eagle mind.

Prepared for the continuing journey through places of unknowing, I feel more assured that way will open through whatever clouds may pass across my path.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.