Moving Toward Risky Solidarity

On May 13, 1985, the City of Philadelphia bombed its own residents. Eyewitnesses watched as the Philadelphia police dropped two bombs containing C4 explosives from a state helicopter onto the home of MOVE, a Black liberation and back-to-nature organization. The bomb shattered the windows of nearby cars and buildings, shook the ground for miles, and ignited a fire that engulfed the MOVE row house. As the fire grew hot enough to melt steel—leaping across houses and streets—police commissioner Gregor Sambor instructed firefighters to “let the fire burn.” As MOVE members and their children attempted to flee the burning building, they were shot at by police until they retreated. In the end, the City of Philadelphia killed 11 Black people, including five children. Sixty-one homes were destroyed; over 200 people were left homeless; and an entire block of one of Philadelphia’s historically Black neighborhoods was left in ruins.

The MOVE massacre was the culmination of rising tensions between the City and MOVE, a conflict that Friends had tried to de-escalate since the 1970s by appealing to Quaker ideas of nonviolence. In this piece, we explore two historical moments in which Quakers aimed to show solidarity with Black liberation: the 1969 Black Manifesto and the 1978 Friendly Presence Vigil. Our work is grounded in research done at the Swarthmore College Special Collections, where we uncovered, analyzed, and pieced together insights from MOVE’s history using the records of the Religious Society of Friends. A critical evaluation of these records shows that Quaker understanding of nonviolence unintentionally helped perpetuate racism, the social structure that makes violence against Black people into a norm.

Calling for Risky Solidarity

Notably, the limits and apprehensions surrounding racial solidarity weren’t unique to Friends’ interactions with MOVE’s resistance. In 1969, the Black Economic Development Conference (BEDC), a national organization aimed at addressing economic disparities in Black communities, issued the Black Manifesto at a Detroit conference. The manifesto demanded $500 million in reparations from predominantly white religious organizations to address the legacy of slavery and the exploitation of enslaved Black individuals. This bold demand aimed to address racial inequities and financially empower Black communities. The response of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting to these demands revealed deep divisions among Quakers. Some Friends recognized the critical need for reparations as a means to right historical wrongs, calling it a necessary “wake up call.” Others were unsettled by what they perceived as the coercive and confrontational tone of the demands, calling the manifesto “violent” and “an unacceptable ultimatum.” This split revealed an internal struggle within the Philadelphia Quaker community to confront and address the deep-seated racism highlighted by the manifesto. Quakers used the idea of nonviolence to differentiate between groups that were worthy of Quaker funding and those that were not. This discourse characterized the BEDC as violent and therefore unworthy of material support.

Quakers failed to translate their theoretical support for racial solidarity into the material practice of reparations requested by the BEDC. After a year of discussion, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting did not reach a consensus, leaving individual Friends to make their own reparations or, more often, to not make them.

Friendly Presence Vigil

In 1978, MOVE operated out of a house in the Powelton Village neighborhood in Philadelphia’s West Philadelphia section. Approximately 15–20 members of MOVE lived there: growing food, composting, and raising animals in the backyard. Materials from the Swarthmore Special Collections document long-standing conflicts between MOVE and their neighbors, who complained—often rightfully—about the 20 stray dogs housed by MOVE, the smell of feces, and compost and debris in their backyard. MOVE responded by encouraging residents to direct their concerns towards the “real pollution” from “cars, insecticides, [and] food additives.” MOVE’s practices were disruptive to their neighbors and intentionally so: MOVE understood the disruption of societal norms as key to the destruction of oppressive systems.

City reactions to MOVE occurred within the context of the redevelopment of West Philadelphia. Powelton was marked as a key location for the expansion of Drexel University property at the expense of low-income Black families. When neighbors complained about MOVE or when the city government cited MOVE for various housing violations, these disputes took place in the context of what we might describe today as “gentrification efforts.” The city’s selective enforcement of housing violations meant that Black residents were expected to adopt white, middle-class values and norms, or to leave Powelton. As the city, West Philadelphia developers, and their neighborhood allies increasingly portrayed MOVE as a danger to health and safety, they fueled the idea that MOVE needed to be removed by any means necessary.

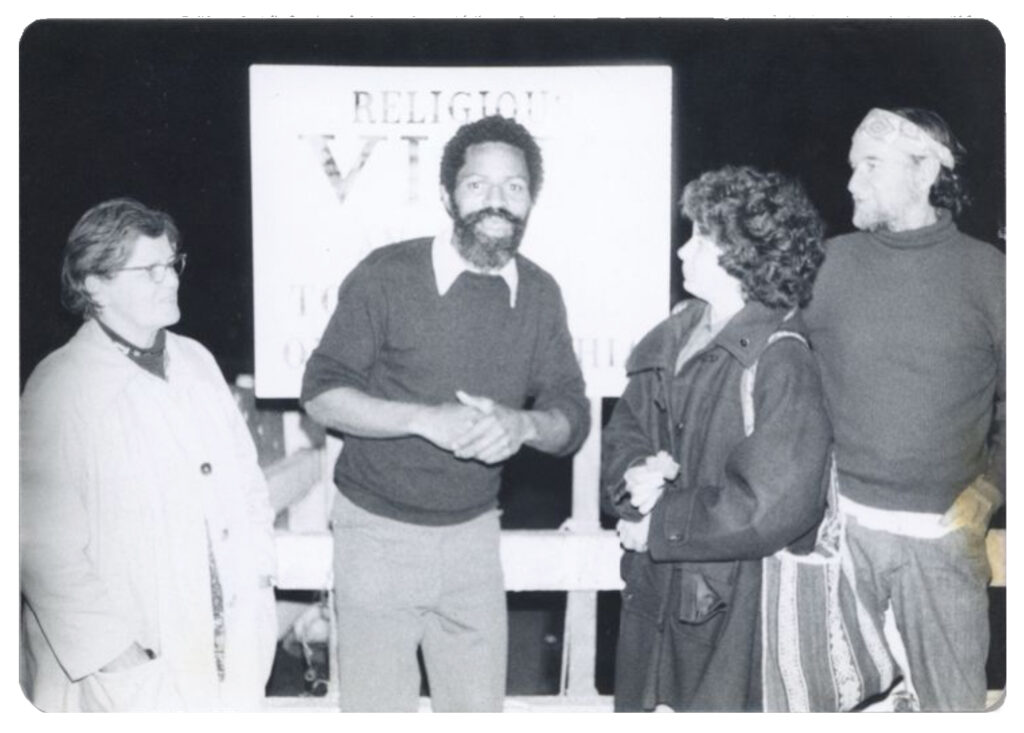

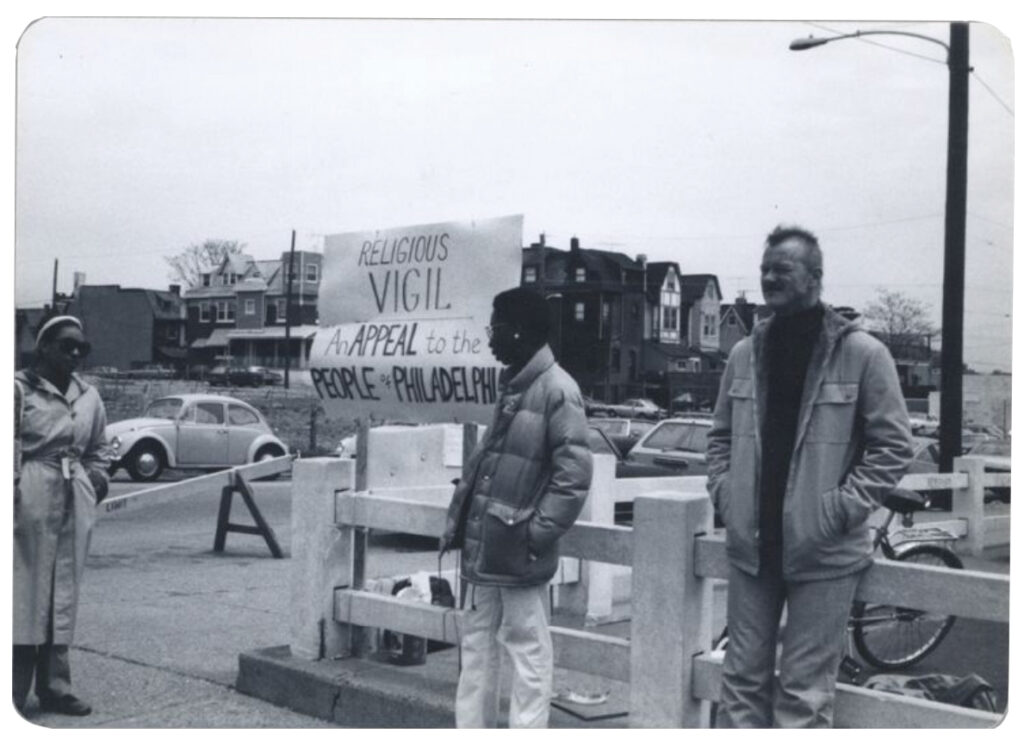

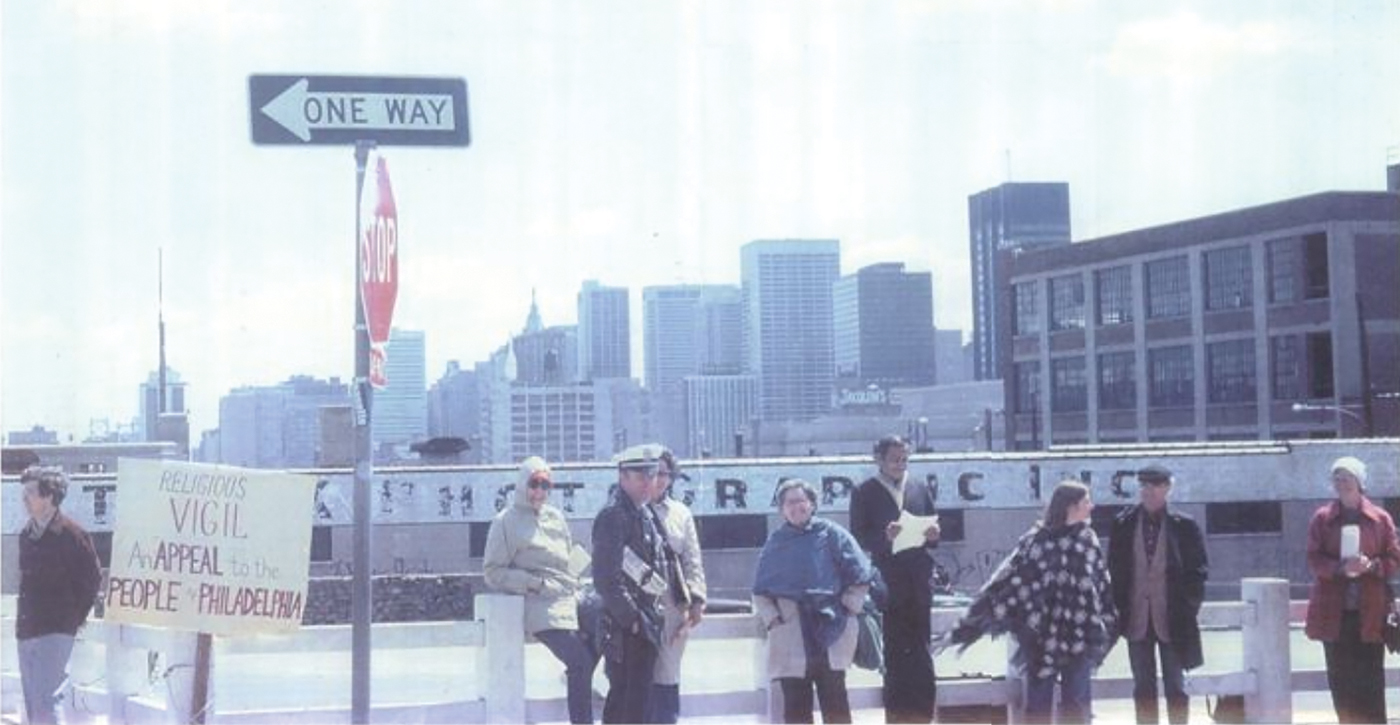

In March 1978, Philadelphia mayor Frank Rizzo blockaded the MOVE house and got a court order to shut off water and electricity. As this so-called starvation blockade continued, the Religious Society of Friends, specifically the Friendly Presence Working Group of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, initiated a vigil. For 27 days, 24 hours a day, they stood in silent prayer on the corner of Race and 33rd Streets, the edge of the blockade. The banner behind them read “An appeal to the people of Philadelphia.” The flyers they handed out said: “Don’t kill them, don’t starve them, keep working on it.” The Friends saw themselves as bearing witness, which they understood as part of Quaker testimony, the lived practice of a commitment to love, truth, and peace.

However, similar to the Friends response to the BEDC, Quaker solidarity efforts once again failed to challenge racial power dynamics. Documents in the archives show the emergence of a specific type of discourse on nonviolence among white Quakers in 1970s and ’80s Philadelphia. This discourse was characterized by Quakers failing to name and address the power imbalance between MOVE and the police, and their resulting passivity during instances of police violence.

In the context of the Friendly Presence Working Group, Friends equated nonviolence with third-party neutrality. In a document titled “Suggestions for Maintaining the Vigil,” the working group said they were holding the vigil “not as automatic partisans of one side against others, but to a way out of the predicament of which we are a part.” In a retrospective memo on the vigil, one of the coordinators, Charles Walker, saw the purpose of the vigil as “peacekeeping” and identified it as “by nature a third-party or nth-party function.”

In a meeting between Friends and Powelton neighbors, resident Jean Byall advocated for the starvation blockade on the grounds that it was “nonviolent,” saying that the police were “forcing MOVE to come out without bloodshed. They do not have to stay in there and starve.” By calling the blockade nonviolent, Byall ignored and silenced what would happen if MOVE did leave: arrests, imprisonment, separation from their children, and the destruction of their home. Unfortunately, Friends’ desire to be “neutral” did not take into account these losses posed by the blockade.

Many standing vigil saw their role to be conversing with the police, rather than protesting to them. In his final report on the vigil, Robert Tatman describes “a feeling of amity” between Quakers and police that allowed for “very frank and open discussions on force, nonviolence, and other highly relevant topics.” In the handwritten log of the vigil, one participant wrote:

I am becoming less pro-MOVE and more objective. I feel good talking to police as people. . . . I’m usually down on cops but I’ve had time here to observe all of the people run the stop signs and be generally inconsiderate not only to the police but other human beings too. It’s sad from all angles.

The entry immediately following reads:

We could see in the distance the demonstration by the Coalition of Black Leaders. . . . [T]hey tried to bring food in to MOVE but +/- 15 people were arrested. Then police w/ horses dispersed the onlookers because the crowd felt positive towards the demonstrators.

These entries are not unusual within the log; there are many accounts of friendly relations between Quakers and police, quickly followed by a description of police action against other groups, particularly those led by Black folk. Onlookers were forcibly dispersed by those on horseback simply for cheering on the Citywide Black Coalition, a Philadelphia-based organization that advocated for human rights and against police brutality. (We were reminded of our own experience at a recent protest in Philadelphia, when police on bicycles began to enclose us, pressing closer and closer until we dispersed.) The vigil log fails to capture the panic and terror of such a moment, precisely because the Friends felt safe, being outside the target of police repression.

Missing here is how Quakers’ friendly feelings towards police during the vigil were present as a function of whiteness. Neutrality relies on the white privilege of watching another group experience violence and having the choice to remain a mere bystander because the violence is not being directed at you.

In the context of systemic violence, Friends self-identification as both nonviolent and neutral posed a paradox. Every aspect of the conflict between MOVE and the City of Philadelphia was embedded in racism, a social structure that disregards the value of Black life.

MOVE was a neighborhood nuisance, the owners of a home flagged by city administrators for various code violations. At the same time, they were a political organization using disruptive tactics to oppose “the system,” which was the concept they used to refer to what we increasingly conceptualize in the United States as white supremacy. In turn, the city’s actions were fueled by the racist rhetoric of the “war on crime.” On a material level, the city’s military-grade response against MOVE was possible because of partnerships between the Philadelphia police and the U.S. military that used increasingly deadly tactics against Black people. The city had a monopoly on violence, which it deployed with overwhelming force against MOVE.

Because Friendly Presence did not name the racial dimensions of the blockade, they quietly normalized the power and violence of racism. They portrayed the vigil as a multiracial coalition, another nod to neutrality.

We can contrast Friends narratives with the Citywide Black Community Coalition, who framed the conflict between MOVE and the City as “part of a continuing history of the flagrant disregard for the human rights of Blacks at home and abroad for over 500 years.” Unfortunately, Friends did not incorporate an analysis of race into their interpretation of the blockade, which limited their understanding of power dynamics between the police and MOVE. Simplifying MOVE and the police as two parties in disagreement and failing to evaluate their power imbalance meant preserving a false peace: empty and without real justice.

In the 1970s and ‘80s, Quaker discourse on nonviolence was characterized by the limits of empathy, the desire to remain neutral in the face of injustice, and its blindness to white supremacy. Accurately apprehending the violence of systemic racism is no small task, yet what the MOVE crisis called for from Quakers was a bolder, riskier solidarity: one that required them to confront and risk their white privilege, standing alongside MOVE with a strong moral stance.

A lived commitment to peace in the world—the heart of Quaker values—may require a loss of material comfort and security. We ask now, as MOVE asked then: are Friends prepared to take this ethical leap?

Land as Reparations

Our discussion on solidarity extends to the ongoing struggle faced by MOVE survivors, particularly in their efforts to reclaim land as a form of reparations, a term we intentionally use to frame this vision of justice for MOVE that demands material redress. The relentless attempts to displace MOVE from their home in Powelton Village were driven by a belief that their presence caused property values to plummet, blocking broader gentrification efforts. MOVE’s steadfast resilience against these powerful forces showed their commitment to advocating for marginalized voices and asserting their right to remain in their community.

Their struggle brings into focus the role of those who aimed to support MOVE. The Quakers, known for their commitment to peace and social justice, attempted to address the conflicts surrounding MOVE through their principle of “bearing witness.” However, their approach during the MOVE crisis often fell short of the risky solidarity the situation called for. The case of a New Jersey Quaker farmer who supposedly offered land to MOVE illustrates this gap. American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) reported on this situation in 1978, suggesting that the offer was intended to ease tensions by relocating MOVE. Despite this, AFSC Quakers later acknowledged their failure to verify the story’s origin, stating, “to this day we don’t know how that story began.”

MOVE, however, denied AFSC’s narrative, asserting that they were never offered land and dismissing the story as one of “the many lies that the Mayor Frank Rizzo administration is telling on the MOVE ORGANIZATION.” These conflicting narratives from MOVE, the Quakers, and local government officials aren’t just differing perspectives; they expose who gets to control the narrative and, ultimately, who has the power to define justice. Each account brings its own perspective, casting the true record of events as fractured and ambiguous. When MOVE denied AFSC’s narrative, they were potentially rejecting a system that silenced their voice and ignored their calls for genuine recognition and justice.

Today, MOVE members, alongside Philadelphia activists, continue to demand the restitution of their house on Osage Avenue, the freeing of political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal, and the full return of the remains of the MOVE children killed in the 1985 bombing by Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania. Their demands stress this need for tangible gestures of material and social repair.

Conclusion

In the 1970s the Black Manifesto called upon white institutions to consider what they owe Black folk and to pay it back; it remains relevant as ever. The Philadelphia City Council established a Reparations Task Force in 2023 that aims to “report on how reparations can atone for the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, and institutional racism in America for Black Philadelphians.” In doing this work, the city has an historic opportunity to acknowledge, confront, and repair the losses inflicted upon MOVE. Offering reparations to Black Philadelphia means offering reparations to MOVE. Honoring MOVE’s needs is one step towards addressing the broader, ongoing struggles faced by the Black community.

In this context, Quakers, too, are faced with the ethical imperative to reflect on their role in racism and direct their energy and resources towards reparations in the present. For over 55 years, Friends failed to collectively respond to the call for reparations issued by the BEDC. To the question how meetings should use their money, we answer: reparations, now. A living testimony to Quaker values could involve directly donating to MOVE’s efforts to reclaim their home on Osage Avenue. Meetings could look into their property holdings and investigate land that could be, or should be, returned. Meetings could follow the example of Green Street Meeting, which has pledged $500,000 towards reparations, primarily focused on helping their Black neighbors keep their homes in the face of gentrification.

We need a Quaker practice of nonviolence that actively creates peace and justice within the world, and we can only do so by confronting racism. History provides examples of what not to do: the ways Quakers failed to show solidarity with MOVE, the response to the Black Economic Development Conference, and the ways that Friends’ white privilege was mobilized to the detriment of Philadelphia’s Black community. Repair is necessary and possible; reparations offer a meaningful, material place to begin.

Online Extra:

The original essay by Natalie Fraser and Chioma Ibida includes many more details, along with footnotes and credits. Read it here [PDF]

Los comentarios en Friendsjournal.org pueden utilizarse en el Foro de la revista impresa y pueden editarse por extensión y claridad.