A Brief History of Meetinghouse Design and the Story of Chestnut Hill Meeting’s New Building

Use the media player above or right-click here to download an audio version of this article.

When William Penn established religious freedom in the colony of Pennsylvania, he offered both Quakers and non-Quakers the opportunity to worship freely without fear of persecution. He also offered them the opportunity to build places of worship for their own use. For Anglicans, neither of these opportunities was new; both were already available to them in England. But for everyone else—from Catholics to Presbyterians to Quakers—the freedoms to worship openly and to build places for worship were nonexistent in England at the time.

Protestants and Catholics took advantage of Penn’s offer and were among the early settlers in Pennsylvania. They organized religious communities and began building rudimentary structures that would later be replaced by elaborate steeple houses of the type George Fox railed against. The original city of Penn’s time has evolved into today’s bustling downtown Philadelphia (also known as Center City), but clear evidence of Penn’s open invitation remains with the presence of 45 active places built specifically for religious worship, representing virtually every Protestant denomination, as well as Catholicism, Judaism, and Quakerism.

Protestants and Catholics could draw on a centuries-long heritage of construction of Christian, religious buildings. They brought these traditions to Philadelphia and over the decades constructed buildings of such architectural distinction that many have been designated as National Historic Landmarks. Among them, ironically, is the Anglican (Episcopalian) Christ Church (1722-54) whose steeple was once the tallest structure in the colonies and remained the tallest structure in Philadelphia for over 100 years. It dwarfed the Greater Quaker Meetinghouse (1755) that was directly across Market Street and gave the early Philadelphia skyline, portrayed by Nicholas Scull and George Heap in their 1754 drawing East Prospect, the profile of a great city.

Quakers, however, brought no similar traditions of religious architecture with them. Up until the passage of the Act of Toleration in 1689, it was illegal for Quakers to construct places of worship in England. Meetings were held in homes, barns—virtually any building available—and very often outdoors. This obstacle helped solidify the Quaker view that buildings are not sacred places and that worship can be conducted “wherever two or three are gathered in my name.”

However, some brave individuals did construct meetinghouses. Hertford Meeting in England, constructed in 1670, is considered to be the oldest purpose-built Quaker meetinghouse in continuous use in the world. Close to it in age are the Brigflatts meetinghouse (1675) and Ifield meetinghouse (1676); both are also in active use today. There were risks in these early efforts, as buildings could be confiscated or vandalized and frequently were.

Since Quakers came to the New World from all sections of England, it is likely that some were familiar with these early English meetinghouses and that they provided guidance for meetinghouse construction.

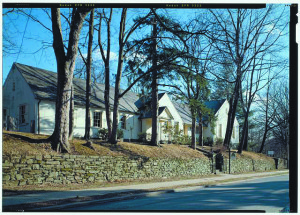

The oldest Quaker meetinghouse in the United States belongs to Third Haven Meeting in Easton, Maryland (1682). Next to that is Flushing meetinghouse in New York (1694). Both are wood frame construction as were many of the earliest religious buildings in the colonies. The oldest meetinghouse in the Philadelphia area is Merion meetinghouse (1695), also wood frame construction.

Although monthly meetings (so-called because members hold business sessions once a month, though worship typically takes place at least once a week) were established quickly in Pennsylvania, most groups held meeting for worship in the homes of members for several years until there was a sufficient population in the area to justify the building of a meetinghouse. Fallsington (Pa.) Meeting (historically called Falls Meeting) is a good example: Friends began meeting in homes in 1680 and created a monthly meeting in 1683, but a meetinghouse was not built until 1690, the first of four to be built on the site. Penn attended meeting for worship here during his first trip to Philadelphia.

As Catherine C. Lavoie points out in her excellent essay on Quaker meetinghouse design (published in Silent Witness: Quaker Meetinghouses in the Delaware Valley, 1695 to the Present), the design of early meetinghouses was influenced by two factors: first, the character of local building materials; and second, Quaker religious practice. With respect to the latter, early meetinghouses can be considered examples of the architectural dictum “form follows function.” There were three primary functions that these meetinghouses had to accommodate: 1) a place for men and women to meet for worship, 2) places for men and women to meet separately for meetings for business, and 3) a place for elders and ministers to sit apart from the general membership and from which they could deliver vocal ministry. A possible, and apparently optional, fourth function was a separate place for youth to sit during worship.

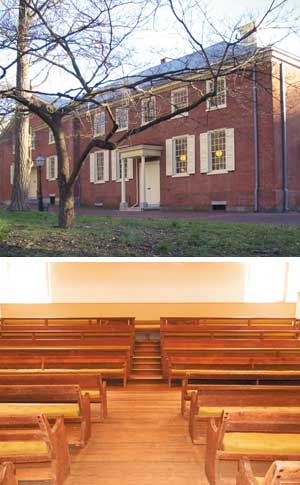

The designated place for elders and ministers to sit was solved by providing “facing benches”—a few benches raised on steps that were oriented to face the rest of the meeting. These are found in the Hertford meetinghouse in England and were generally found in Pennsylvania meetinghouses up until 1898. A separate area for youth, when needed, was solved by providing a balcony or gallery. The solution for a place to worship plus separate places for business meetings evolved over time. The early solution was a single main room capable of being divided into two smaller rooms for business meetings by a movable partition in the center. Many examples of the partition solution can be found among older meetinghouses in the Philadelphia area, including Merion Meeting and Upper Providence Meeting (1828). Eventually the design evolved into two separate rooms with one often slightly larger to accommodate joint meetings for worship; Arch Street’s meetinghouse (1804-11) is the largest example of this arrangement.

The designated place for elders and ministers to sit was solved by providing “facing benches”—a few benches raised on steps that were oriented to face the rest of the meeting. These are found in the Hertford meetinghouse in England and were generally found in Pennsylvania meetinghouses up until 1898. A separate area for youth, when needed, was solved by providing a balcony or gallery. The solution for a place to worship plus separate places for business meetings evolved over time. The early solution was a single main room capable of being divided into two smaller rooms for business meetings by a movable partition in the center. Many examples of the partition solution can be found among older meetinghouses in the Philadelphia area, including Merion Meeting and Upper Providence Meeting (1828). Eventually the design evolved into two separate rooms with one often slightly larger to accommodate joint meetings for worship; Arch Street’s meetinghouse (1804-11) is the largest example of this arrangement.

When Chestnut Hill (Pa.) Meeting was founded, it departed from prevailing custom in both organizational and physical terms. At the time of its founding in 1924, the split between Hicksite and Orthodox Friends still existed in Philadelphia. Rather than join one of these yearly meetings, Chestnut Hill joined both of them as Chestnut Hill United Monthly Meeting, becoming the first monthly meeting formed by members of both the Hicksite and Orthodox Yearly Meetings. In terms of physical design, the meeting also substantially departed from the past, reflecting changing Quaker practice in the twentieth century.

The meeting was formed by a group of families living in Chestnut Hill, led by husband and wife Robert and Elizabeth Yarnall. Initial meetings were held in an office in Robert Yarnall’s steam equipment factory. An inner ring of small chairs in front of a large fireplace accommodated children, surrounded by an outer ring of larger chairs for adults. When the time came to build a meetinghouse in 1932, Yarnall donated a piece of land on the site of his factory. The meeting room was the first to be designed without any facing benches and had only one meeting room, rather than separate rooms for men’s and women’s business meetings. Nor was there a separate balcony provided for youth. The form of the meeting room carried over the intimate character of the initial meeting place: a rectangular room with a relatively low ceiling, much like a comfortable living room in a Chestnut Hill house, complete with a large fireplace symbolic of the meeting’s origin. A social room and classrooms were added in 1964, but the meeting room remained relatively unchanged. Over its many decades of use, members and attenders have commented on the intimate character of the space and how that intimacy has contributed to the spiritual quality of meetings for worship.

By the 1980s, some members began to have concern about the small size of the meeting site. The land given allowed only for the meetinghouse itself with no space for parking or expansion. Parking was available on the Yarnall factory lot, but once that company was sold, moved, and its property sold to new users, the concern for parking became more acute. By the 1990s, other concerns emerged: there was no convenient handicapped access except through the adjacent property now owned by the United Cerebral Palsy Association (UCPA), and conflicts with UCPA’s needs limited the meeting’s ability to rent space in the meetinghouse for other functions.

The Yarnall factory property included two parking lots, and UCPA made use of only one of these, the other remaining undeveloped. Public and private developers had looked at the empty plot as a possible site for a public school, low-income housing, or high-rise housing for the elderly. When the last of these proposals faded away, the meeting decided to acquire this lower parking lot, a former stone quarry. Making this decision is what might be called a defensive action as there was no immediate need for the property. It was viewed as a potential site for parking in the future if that was ever needed or alternatively if the meeting later decided to sell the land, it could at least ensure that its use would be consistent with the adjacent residential neighborhood.

Once the property was acquired, two new factors influenced the meeting’s decisions. First, it was generally recognized that the existing meetinghouse no longer sufficiently met Chestnut Hill Meeting’s needs. In spite of the extremely cooperative attitude of UCPA in sharing its parking and access for the handicapped, these issues remained concerns. The meeting had grown in membership with an increase in the number of young families with children such that neither the meeting room nor the classrooms for religious education met current needs. The building needed investment and expansion.

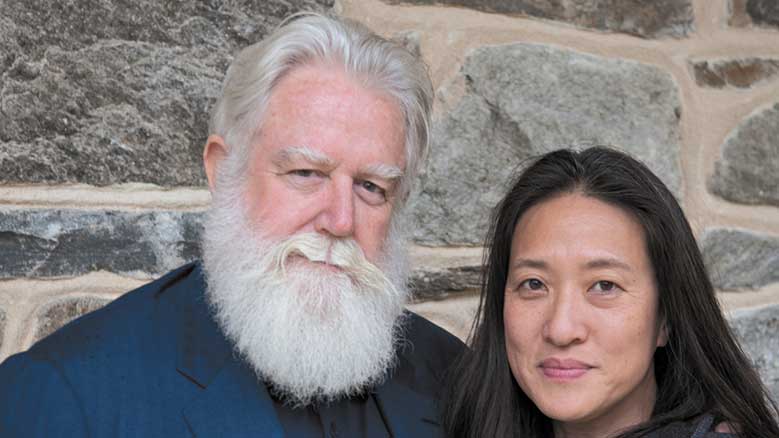

Second, a creative idea for the redesign surfaced when a member of the meeting read an article about the then new Live Oak Meetinghouse in Houston, Texas, with Quaker light artist James Turrell’s Skyspace (completed in 2000). She visited the meetinghouse and returned to share an enthusiastic report with the meeting; others traveled to Houston returning with a similar reaction. When Turrell expressed interest in designing another meetinghouse, the discussion of building a new meetinghouse for Chestnut Hill began in earnest.

The resulting decision did not come easy. The discussion occurred in four phases over about ten years, a period which tested the meeting’s commitment to Quaker process and its members loving relationship with one another. The first phase addressed the issue of whether it was appropriate to build a new meetinghouse at all; various questions were explored: Would it not be more environmentally responsible to upgrade and enlarge the existing meetinghouse? Would it not be more appropriate to use the millions of dollars that a new meetinghouse would cost for social programs instead? Would the meeting be able to raise the needed funds? Is Turrell’s Skyspace a work of art, and if so, is it appropriate to have it in a Quaker meeting room? (One prominent architect, a lifelong Friend, refused to even be interviewed for the job because he believes the Skyspace is a work of art and therefore inappropriate to be installed in a meeting room.) Over several years the meeting listened carefully to the different points of view about these issues, invited Turrell to speak, and organized visits to see the Live Oak Meetinghouse in Houston. In the end, it was decided that the sense of the meeting was to move forward with plans for a new meetinghouse.

The second phase consisted of determining the design of the new building. This process was a collaborative effort that engaged all members of the meeting and was coordinated by the equivalent of a building committee working with Turrell and architect James Bradberry. Once a conceptual design was adopted they were joined by environmental design consulting firm Re:Vision Architecture; project manager John R. Howard of Becker & Frondorf; landscape architect advisor Carol Franklin of Andropogon Associates; and general contractor firm E. Allen Reeves, Inc. Josh Janisak of James Bradberry’s office added the final touch, designing the new benches for the meeting room.

The third phase was fundraising. While most of the funds were contributed by meeting members (along with the sale of the existing meetinghouse to UCPA), many non-members contributed to support the Turrell installation based on the meeting’s commitment to open the Skyspace to the general public at dawn and sunset (the best times to view it) and to make the space available for community events. Contributions toward the $5 million total cost were also made by the William Penn Foundation; the National Endowment for the Arts; the Samuel S. Fels Fund; the Connelly Foundation; the McLean Contributionship; the Goldsmith Family Foundation; and the Knight Foundation; as well as two Quaker foundations, Shoemaker and Tyson.

The final phase was the actual construction, and this too had its challenges. The first was the decision to hire a union or nonunion contractor. Philadelphia is a union town when it comes to the construction industry. However, the difference in price was so significant, the meeting eventually decided to hire E. Allen Reeves, Inc., a highly respected, nonunion general contractor that had built structures for other Quaker organizations. During construction, one act of vandalism occurred, but it was so highly publicized that the supportive reaction from the public probably acted as a deterrent to any more incidents.

The completed meetinghouse consists of two components linked by a spacious lobby and gathering room with views of the site and a tree-lined hillside that borders part of Fairmount Park. The gathering room contains a fireplace (itself the subject of much debate), continuing the historic tradition of a fireplace in the meetinghouse. To one side of this entry area is the meeting room with a high, arched ceiling and tall windows on three sides, shaded by an exterior surrounding porch reminiscent of earlier meetinghouses. The room houses the Turrell Skyspace, a rectangular opening in the roof for viewing the sky along with specially designed cove lighting around the perimeter of the meeting room. The Skyspace is closed during meeting for worship and opened at dawn and sunset twice a week via a sliding roof. The unique lighting designed by Turrell enhances a Skyspace viewer’s perception of the sky in an almost magical way, creating a beautiful atmosphere that nurtures peaceful and spiritual meditation and worship.

To the other side of the lobby and gathering room is a two-story structure with space for meeting functions. The first floor contains a two-story high social room with exposed wood trusses, a kitchen, bathrooms, and a committee room; First-day school classrooms are located on the second floor, one of which opens onto a roof deck above the lobby and gathering room area.

In order to design the most energy-efficient building, computer energy modeling was used to help select building materials, insulation, operable windows, and a zoned heating and air-conditioning system. The roof of the two-story structure has been designed to allow for the later addition of solar panels.

As with its first meetinghouse, Chestnut Hill Meeting has once again departed from tradition while at the same time trying to relate to the long heritage of Quaker meetinghouse design in the Philadelphia area. The meeting room with its Turrell Skyspace is an unusual contemporary feature, while the simple form of the building itself (with its surrounding porch, pitched roofs, and use of simple materials) harks back to the simplicity of early meetinghouses in the Philadelphia area.

Come visit and see for yourself. Go to chestnuthillskyspace.org for more information on the building’s design, visiting the Skyspace, and how to reserve the space for an event.

Read more about the Quaker artist James Turrell in “James Turrell: Beyond the Skyspace” by Gail Whiffen.

[…] Read the story of Chestnut Hill Meeting’s new building and a brief history of meetinghouse design in “The Freedom to Build” by John Andrew Gallery. […]

Hiring union labor is important. Unions allow workers’ families to live a stable decent life. If the cost of hiring union labor was so much higher than that of hiring non-union labor, did Friends go to the union and ask for a hardship reduction in rates for a non-profit project? Did Friends attempt to understand and prevent the anger that led to the workers’ committing sabotage. I understand that the creation of great art or the creation of a sacred space can sometimes be more important to a community than taking care of more prosaic needs for food, education, retirement security, but how much overlap is there between the Friends, etc. who will benefit from the facilities (one community) and the people hired to build it (another community)? It is probably true that most Friends’ institutions are very sensitive to cost, and perhaps the majority hire exclusively non-union labor for that reason, but where does cost fall within the hierarchy of factors we consider when we decide to undertake a major project? Is cost always near the top? Is economic justice always near the bottom?

We might ask why is a non-union general contracting company “highly respected” if it denies its employees the benefits of having a union? Is this the kind of institution that Chestnut Hill Meeting and other Quaker institutions want to support? For a union to maintain a “thug squad” that sabotages non-union projects is abhorent and extreme, I admit, but one can understand why working class people might resent being passed over, dismissed or snubbed by an organization that has enough surplus funds to build a lavish addition so special that even photographing its interior is forbidden.

The article refers to a supportive reaction from the general public (I assume this means supportive of the Meeting and/or the non-union contractor, not the union or the saboteurs). Did that general public include working people who have, aspire to or desperately need union jobs?