All my love

To you and yours

And all the college boys, they’re dressing up in suits

Thinking life’s a war

—Henry Jamison, “Boys”

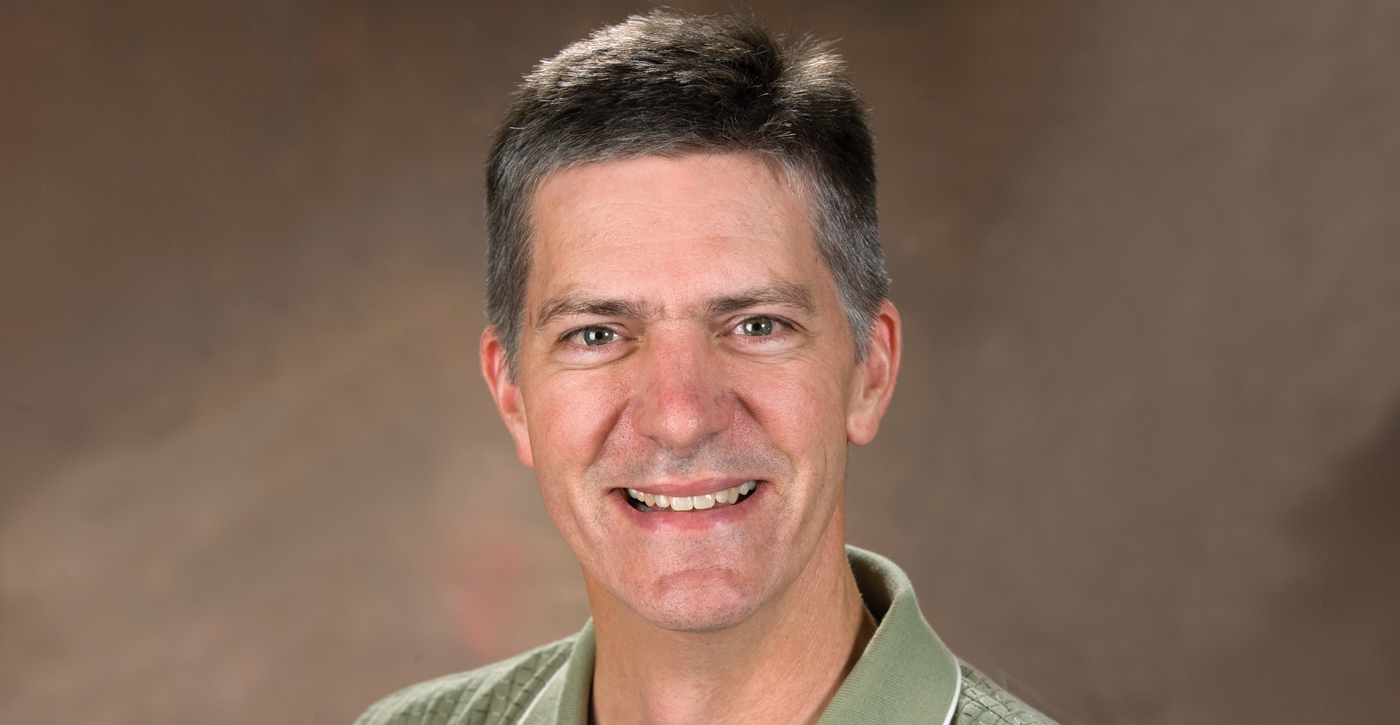

The first time Scott challenged me to a game of racquetball, I thought he might be joking. As the director of the Quaker Leadership Scholars Program at Guilford College, Scott struck me as wise, spiritually grounded, present, and intentional. He did not strike me as athletic.

At the time, I was a freshman at Guilford. I was on the ultimate frisbee team. I regularly went on long backpacking trips, and I played pick-up soccer. I was in the best shape of my life. While I had never played racquetball, I was pretty sure I would smoke him on my first try. I accepted his challenge and prepared to experience the satisfaction of humiliating my respected elder and mentor.

Growing up the youngest of five boys in an intentional community, I developed an intense sense of competition early. Whether it was ping-pong or Mortal Kombat, intellectual strategy games or athletic ones, I had to try twice as hard to keep up with the boys three- to five-years older than me, whom I desperately respected. I obsessed over bettering myself at every activity we did together and was often rewarded by being included in the next game.

In adulthood, my sense of competitiveness hasn’t diminished. I moved to Philadelphia in part because I found a pick-up volleyball game I really liked. (The best part of that story is that I didn’t really know how to play volleyball.) But whatever it is—volleyball, chess, tennis, badminton, bocce, dragon boat racing—regardless of whether I’ve played it before, if it is a sport or a game, I will play it, and I will try to beat you at it.

As a lifelong Quaker, it hasn’t always been clear what to do with my strong predilection toward competing with others. We are a nonviolent people who believe in the spiritual equality of all people, so Quaker groups tend to gravitate toward inclusive activities and have a distaste for ones that have winners and losers.

As a young Quaker, I could sometimes play off my competitiveness as a cute personality quirk, like the time I challenged Joey, an all-state wrestler, to be my partner in Wink. My theatrical yelping as I was dragged around the meetinghouse was, I hope, endearing for those watching. There were other times that my tendency to compete with peers manifested in ways that, in retrospect, were unhealthy for my friendships and communities.

The echoes of my failures bounced off the walls for an awkward eternity… Mercifully, the game was over. With my hands on my knees and my lungs clawing for air, I looked at Scott. He hadn’t broken a sweat.

Five minutes into my first racquetball game with Scott, I knew that I had made a terrible miscalculation. I was discombobulated, sweating buckets, and completely out of breath. I had full-body collided with each wall of the court at least once. At one point, I severely miscalculated the trajectory of a ball and instead of the ball hit myself in the shin with my racket—hard. A welt started to form. Despite the intensity of my effort, I had barely touched the ball.

Meanwhile, Scott was standing in the center of the court, calmly calling out the score and serving the ball consistently to one corner or the other in a way that was impossible to predict. Whenever I did get lucky enough to make contact, the ball was so close to the wall that my racket barely scraped it off.

There is no sound dampening in a racquetball court. The echoes of my failures bounced off the walls for an awkward eternity. I watched the back of Scott’s head as he prepared one last serve, and swore that this would be my moment. The ball approached in a long arc that bounced off the back wall and rolled—literally rolled—down the side wall. My racquet scraped the wall as I swiped and missed. Mercifully, the game was over. With my hands on my knees and my lungs clawing for air, I looked at Scott. He hadn’t broken a sweat. The score was 15 to zero.

Racquetball, it turns out, is not simply a game of athletic ability.

Whatever I loved about sports, it didn’t seem worth feeling that badly about myself or causing others to feel badly about themselves.

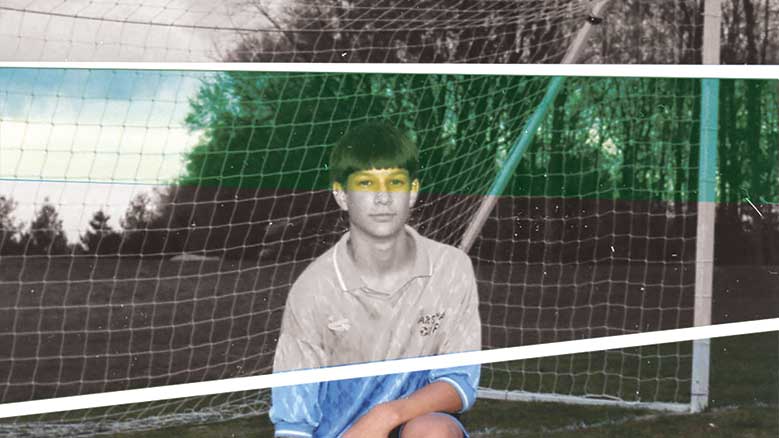

When I was 13, I joined a travel soccer team composed of other 13-year-olds from surrounding counties. Excited to step up my game and make friends who didn’t go to my school, I was surprised to discover a group of boys whose nastiness toward opposing teams was only surpassed by their vitriol toward one another. As the new guy, I was openly taunted. I remember one particularly intense bully on the team laughing as I was hit in the face by a hard-driven shot while retrieving my own ball from the goal during practice. Stunned and embarrassed, tears came to my eyes. My teammate recruited others to laugh at how red the side of my face became and the fact that I was apparently a crybaby. The coach was standing right there. He didn’t intervene.

There is no question that the warlike, domination/conquest model for competition in our culture is toxic. I played poorly that season on the travel team and soon dropped out of soccer altogether after finding a similar dynamic on other teams. Whatever I loved about sports, it didn’t seem worth feeling that badly about myself or causing others to feel badly about themselves.

In “Friends and the Understanding of Reason and Equality” from the April 2011 Friends Journal, Caroline Whitbeck writes, “A key value in contemporary competitive U.S. culture is to avoid being a loser. . . . Gospel Order rejects the win-lose model and shows us our part in the abundant life.” I get it. When we equate competition with domination, it’s better to abstain altogether.

So what am I to do with the part of myself that still wants to compete?

Body awareness, spirit awareness, and awareness of the miracles all around us combined to form a sort of cauldron, a refiner’s fire. We would emerge from the racquetball court sweating, laughing, broken, whole.

Scott Pierce Coleman continued to pound me in racquetball until he didn’t. When the day came that I could give him a serious challenge, we both seemed relieved. When you’re of equal skill to an opponent, the difference between winning and losing is mostly in your mindset. As a young man and a college student going through a lot of growth, transitions, and challenges, my mind and spirit were all over the place. Scott would use the opportunity to notice my energy or lack thereof, my focus or distraction, and he would ask me about it between games. Often I didn’t know how I was doing until I played a game with Scott and he would ask me a series of pointed questions afterward. It became one of the most powerful spiritual friendships I’ve ever had.

The games themselves are hard to describe. Racquetball as a sport requires a lot of spatial awareness and a strange sixth sense about the location of a ball, struck and spinning, after careening off three walls in quick succession. Things happen so fast that you don’t have time to make conscious decisions. The body makes them for you.

When Scott and I would push ourselves to our limits, magical things would happen: shots that we didn’t expect to get to, moves by our opponent that we inexplicably anticipated, and repetitions that seemed statistically impossible. Body awareness, spirit awareness, and awareness of the miracles all around us combined to form a sort of cauldron, a refiner’s fire.

We would emerge from the racquetball court sweating, laughing, broken, whole. I remember returning to my dorm and trying to converse with my peers who were talking about papers and parties, who was sleeping with whom and why it mattered. In those moments, I couldn’t relate. I was too caught up in their beauty, the beauty of this day we are given, and the miracle of breath and of life.

When a performer breaks through the regularity of their performance, and witnesses get a glimpse of God.

The only TED talk that ever changed my life was by Elizabeth Gilbert. It is called “Your Elusive Creative Genius.” (You should go watch it right now.) Her description of the origin of the word olé is beautiful: when a performer breaks through the regularity of their performance, and witnesses get a glimpse of God.

I experience this playing sports. There were moments that Scott and I played a point to the edge of our abilities and beyond, repeatedly hitting better shots and more challenging shots than we knew we were capable of. It became a delicate, escalating, miraculous dance, an out-of-mind experience: mystical, inexplicable, unquestionably worthwhile.

When I’m in a deep worship, a gathered meeting, it feels like my consciousness has expanded to fill the room. I know I’m there when I can start to feel the corners. Racquetball is all about the corners. In those moments of superhero strength—swinging my racquet without looking and being in the exact right place without knowing why or how I got there—the corners of the room were like an extension of my body. And Scott, by putting in full effort and encouraging me to put all of my energy, focus, and attention into besting him, helped me get there.

Life is not a war. Sports and other competitive games don’t have to be either.

Wonderful article! Enjoyed hearing your stories, and definitely relate to the spirituality of being fully present in my body, which I experience through dance.

I appreciate this article. I’ll have to check out the whole issue. I’ve been disappointed in the limited view of some Friends when it comes to competitive sports. My kids all compete in sports of one kind or another. My teenage son is particularly enthusiastic about football and is a talented enough player to have played on his high school varsity team as a sophomore. Over the years, a few Friends have been encouraging, but many have not hidden their disapproval. It makes me sad. Friends we have known for his whole life seem not to have considered that we HAVE labored with the issues of competition and competitive violence with him. Few have bothered to ask us about that process. Even fewer have seemed interested to know what life lessons my son gains from participation in this highly competitive sport. He gains a lot! He gives a lot too, using his athlete status to quash unkind teasing in the classroom, for example. (A trait Friends can take some credit for!) In spite of his character, curiosity and kindness, I’m afraid he’s gotten the message that competitive, athletic young men like him are only marginally welcome in the SOF.

Thanks so much for this great article Jon. What a profound spiritual lesson your young friend taught you.

What a joy to learn about the guy who puts Quaker Speak together. Our Great Falls Quaker worship group gathers for Quaker Speak many Sunday mornings and then discusses the subject. Thanks, Jon. Starshine

Jon, I love your article! Maggie, I second that emotion… finding Spirit in dance. Just yesterday, in a spiritual conversation with a peer (who had also come of age in the 1970s), I was indulging in fond memories of disco dancing. The disco is one place I could sometimes achieve flow state. My friend agreed, adding: “God is a disco ball, and each mirrored facet is like one of us, reflecting the Light!” A fine effort — finding God in places Wordsworth and Coleridge wouldn’t have thought to look.

Jon, I enjoyed your article. I grew up playing sports and was fortunate enough to have coaches who taught me to love winning instead of hating to lose. As a collegiate volleyball player and swimmer, I learned both teamwork and individual perseverance. One thing that you inferred but didn’t elaborate on is “the Zone.” That all too brief moment when mind, body, and spirit converge in perfect harmony. That moment that is often described as, “time slowing down, the ability to see not only where people are but where they are moving to, that breakthrough when the muscle memory, knowledge of the game, and prescience of the relationship of movement, connect.” The first time I experienced the Zone I was completely in the present moment and when I realized what I was experiencing… Poof it was gone! I have also been blessed to experience this in Meeting. The Gathered Meeting is an experience that brings us together in a mystical way. It is not competitive but once in “the Zone” of a Gathered Meeting it keeps bringing us back seeking that same awe as a game with a friend or team that loves to win!