A Vietnam War Resister’s Journey of Conscience

Sometime in 1968, I received a 3-A Selective Service deferment, “married with children,” which replaced the 2-S student deferment I had while in college. I felt that concerns of being drafted after college were now an unnecessary worry.

I was shocked and surprised when in 1969 I opened the letter from the Selective Service Board that informed me I was reclassified 1-A and draft eligible. I had graduated, begun graduate school in education, and brought my wife and two daughters together in a rented house. I worked at a custom house brokerage firm doing paperwork for goods crossing the American and Canadian border in Niagara Falls, New York. I was able to work around my education classes to support my young family. My 2-S deferment wouldn’t extend to graduate school, but I assumed my 3-A married with children deferment was golden. I was terribly wrong!

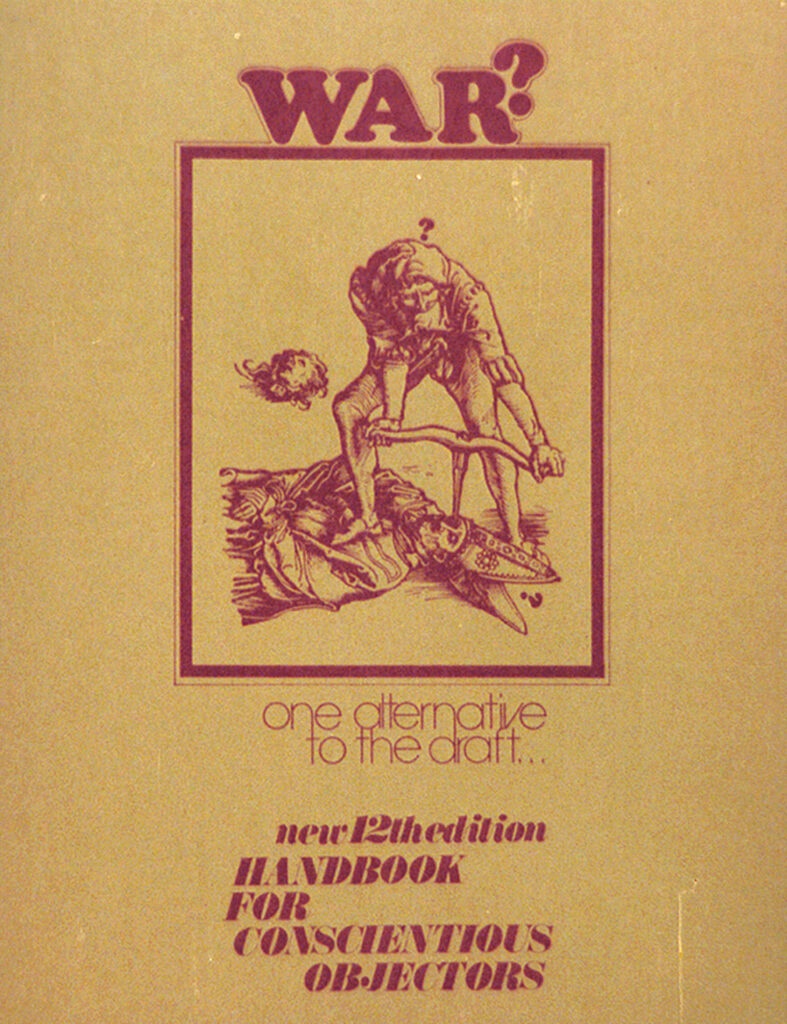

In some publication, somewhere, I saw an ad for free draft counseling. It was sponsored by the Quakers, a religious group of which I knew very little (I associated them with beards and pacifism). The Quakers were at the forefront in providing draft counseling during the Vietnam era, helping drafted individuals know their options, including conscientious objection and alternative service. The counselor I met was young, laid back, quiet spoken, and bearded. He had such a sense of peace about him that the screaming in my brain and gut seemed out of place. I almost renounced my Catholicism on the spot to take up the torch of the Quakers. I had yet to become a fan of the Holy Spirit.

“William” examined the paperwork I provided, shook his head, exhaled, removed his glasses and fixed his eyes on mine. After a pause, he began to explain that this was not a mistake but a legal progression of reclassification and that, in fact, I was draft eligible. I was stunned, shocked, and mad as the screaming reached new heights in my brain and gut. After a reasonable passage of time for me to collect my thoughts and composure, he began to explain.

William told me that during my freshman year of orientation, I was given a waiver to sign which resulted in my initial 2-S deferment. The waiver part, he explained, was in the fine print. By requesting the student deferment, I waived my rights to any future deferment after leaving college or graduating. I tried to remember freshman orientation. We reported to the school gym, where hundreds of us were guided from table to table to sign or pay for things. It was a confusing atmosphere: class schedules, student IDs, health cards, etc. I remember stopping at a table labeled “ROTC,” which was mandatory our first two years of school (the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps is an officer training program for college students). I believe it was there that I signed the ill-fated document, the 2-S deferment paperwork. I did not read it, receive a copy, or think much about it as I shuffled off to the next table. Now four years later, I was paying the price. Realistically I would have signed it anyway, but I should have at least been given an explanation of potential ramifications in the future.

My Quaker counselor, William, explained that when I married during my senior year, I was given a 3-A married deferment because it was a better deferment. When I graduated, however, the 2-S waiver kicked in, and I was reclassified 1-A because I was no longer an undergraduate student. I had waived my rights to any future deferment, including that 3-A “married with children.” William also explained that I should expect to be drafted soon, and that when I was drafted, there was a procedure that, by law, had to be followed and that he could help me delay my induction. It was all legal: using the system’s procedures to our advantage. There was a glimmer of hope; buying as much time as possible would keep that glimmer of hope alive.

When I received the anticipated notice, I was still shocked and surprised. I wanted to sort out my feelings about my best friend’s death in Vietnam, the war, the draft system, and what would be best for me and my family. I made an appointment with my Quaker draft counselor to set in motion my response to my draft notice.

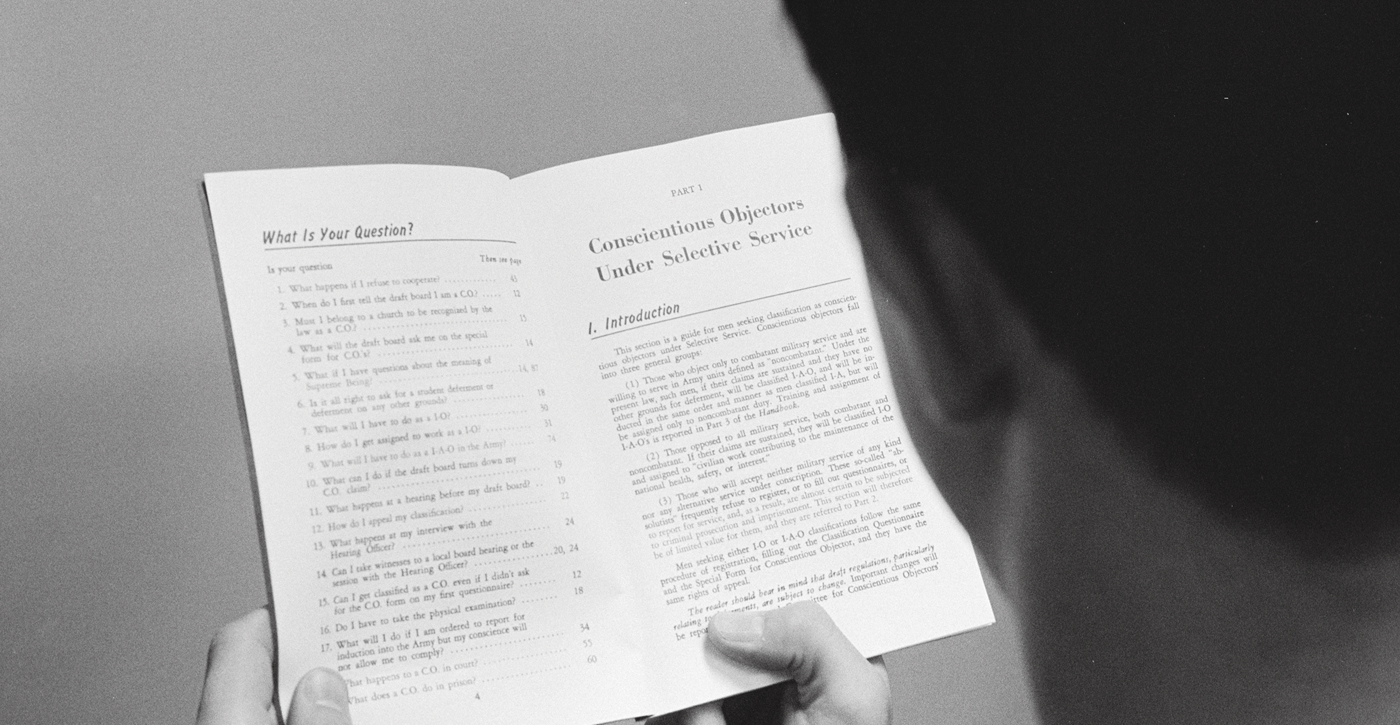

William explained that with each step in the process, there were time limits with deadlines. Answering the draft notice, appealing the reclassification, meeting with the draft board, and further appeals of draft decisions all came with time limits and deadlines. If all failed locally, the final appeal was to the state draft board, though it rarely overruled a local draft board’s decision. Our tactic was to wait until the legal last minute to file requests and to send everything certified mail to create a paper trail of our intentions. If a deadline was 30 days, we would wait until the twenty-ninth day to send our response. The postmark was everything.

During the process, I was in deep thought and worry. What exactly were my feelings about being drafted, serving in the military, fighting in a war, and the risk of being killed or maimed? I had protested the war on campus and was concerned when my best friend sent me letters from Vietnam pointing out the futility of the war. I was devastated when he was killed by a sniper in an offensive in Quảng Trị province. I felt like he felt: that we were languishing in a politician’s war that we couldn’t win even at the expense of our youth. I decided I would not serve.

My first thought was to relocate to Canada. I traveled to Toronto to check out the Canadian underground movement and meet with U.S. draft resisters who relocated there. It was a very depressing experience. We sat on a stoop outside a draft resistance headquarters and listened to stories of Americans unable to find meaningful work, who were living in poverty, unable to have meaningful contact with family and friends back in the United States. When I re-entered the United States, I decided running away was not the answer for me. Why should I have to renounce my citizenship and relocate because pathetic politicians were unwilling to do the right thing with this unjust war?

To refuse to go into the military is a criminal offense, a felony. That would eliminate a career in education or government, especially since I would probably serve one or two years in prison. With the help of William and the Quaker tradition, I decided to apply for conscientious objector status so I could at least publicly express my views before being dragged off to prison.

Before I formally applied for conscientious objector status, I was summoned to my local draft board for a hearing. The members were local citizens, some of whom knew me and my family. One asked why I wouldn’t serve my country like my uncles and father, a former Marine. Another asked why I wouldn’t want to enter the military; since I graduated with two years of ROTC, I could be a second lieutenant. I explained that I was vehemently against the war, that my best friend and “brother” had died in that distant hellhole, and the life expectancy of a second lieutenant, according to my ROTC staff sergeant, was about 28 seconds. I also explained that I fought hard to disrupt my ROTC classes in my second year and that my father, the Marine, was not a patriotic fan of this gruesome war. My appeal was denied, and I began the process of seeking conscientious objector status.

The draft physical notice came, and I was scheduled to travel to Buffalo from Niagara Falls. We reported to a recruiting station and a number of us boarded a bus on a Saturday morning to travel to our draft physical.

Applying for conscientious objector status was complicated and exhausting. The questions caused me to examine everything I believed in. I undertook a comprehensive, in-depth analysis of what I think about conflict, violence, and pacifism on a variety of levels.

National Security Questionnaire

The physical was a nonstop humiliating experience under the watchful eye of the military. We rushed from station to station in our underwear. We were probed and prodded, even bent over with our hands on our ankles to check for . . . I thought I had a chance of failing the hearing test because of all the earaches and a punctured eardrum I had as an adolescent, but my hearing wasn’t quite bad enough. The tech informed me they were damaged but good enough for the Army.

Finished, we dressed and assembled in a large room with desks and chairs; we were ordered to sit and were served box lunches. There was a sandwich (baloney I think), an apple, and a Hostess cupcake. I was so upset that food from the Army was the last thing on my mind.

A couple of uniformed enlisted men began passing a form to all of us potential inductees. The desk sergeant seated in front of us explained that this was the final step of the draft physical. It was a national security questionnaire and needed to be filled out and signed to expedite security clearance if and when you were drafted into the armed forces. This was voluntary! I looked at the first page and began to read:

Are you now or have you ever been a member of the following organizations?

The Communist Party

The American Nazi Party

The Daughters of Garibaldi . . .

The list continued, and the more I read, the more ridiculous it all seemed. It just added more anger to the whole process. If I were a member, would I admit it? Anyway, I put down the questionnaire, leaving it blank.

Soon we were told the bus was waiting and that we should finish our lunch, file out returning the questionnaire to the desk sergeant, and board the bus. Suddenly, the desk sergeant turned and stopped me in my tracks. I returned to his desk, and he explained that I hadn’t completed the questionnaire. I explained that he said it was voluntary! He smiled and agreed it was voluntary but explained that by not signing it, I could be admitting that I was, in fact, a member of one or more of these organizations. I was stupefied by the illogic. Now more than ever, I was not wasting my time on a dumb-ass piece of paper! He asked if I would reconsider, and I said no.

The next thing I knew, the sergeant was escorting me to an office. I entered a small room with a desk, typewriter, and chairs. I sat. The sergeant went into another office. He returned with a captain and a woman who sat down at the typewriter. He introduced himself and said that the secretary would type my answers to questions he was about to ask. I asked if it was voluntary, and he replied, “Yes.” I told him I would rather not answer any questions. The sergeant asked if I was to be held overnight; the bus was waiting. That sent a shiver down my spine! Held overnight by the army, in Buffalo! I would never be heard of or seen again! Fortunately, the captain told the sergeant to put me on the bus.

William was quietly amused when I told him the story. He told me that by not having signed the form, my induction would be delayed by possibly six months. They would have to do a security background check on me to see if, in fact, I was a member of some subversive organization. Soon it dawned on me that my father worked for the federal government and had top-secret clearance. The paranoia set in, and now I had an additional worry. The investigation did delay my induction and my father kept his job.

Applying for conscientious objector status was complicated and exhausting. The questions caused me to examine everything I believed in. I undertook a comprehensive, in-depth analysis of what I think about conflict, violence, and pacifism on a variety of levels. William guided me but let me discover on my own the answers to questions that could decide my future. He probed my answers with more questions, and I was forced to re-evaluate my commitment to pacifism.

One of these questions prompted me to think about it for a long time: “Would you serve in the armed forces in a non-combative capacity, such as an army medic?”

I could avoid imprisonment and a felony conviction if I were accepted by the military in this capacity. Ultimately, I rejected this idea because I would be supporting the military as a member, and I was no longer willing to compromise. I relied on my Christian faith and the teachings of Jesus Christ to frame my answers, as well as William’s Quaker influence.

The Intervention of the Holy Spirit

The application for conscientious objector status reached the state level. In an unprecedented decision, at least in this case, they voted five-to-zero to restore my 3-A married deferment! I suppose they felt this was a better choice than recognizing another pacifist on this planet!

Conclusion

I have abandoned my Catholicism over the years for a variety of reasons: divorced members denied the sacraments; priests not allowed to marry; women not allowed ordination; and the history of the Holy See in a number of embarrassing circumstances, with extensive sexual and physical abuse in the forefront!

My spirituality and reliance on the Holy Spirit have only increased over the years and continue to give me comfort during these incredibly challenging times. I plan to continue on this path and explore the Quaker experience again, after all these years.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.