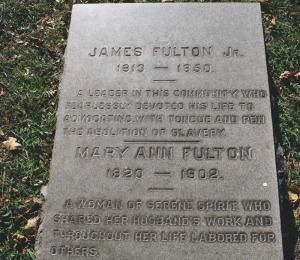

While serving recently as a docent at my meetinghouse, Fallowfield Meeting in Ercildoun, Pa. (a role which includes detailing the documented history of abolitionists associated with the meeting), I heard an attentive, non-Quaker visitor muse aloud, “I did not know there were black Quakers.” My reply was warmly, “Yes.” Taking it as a safe cue to engage in conversation, she quizzically asked, “Is it because they helped your people become free?” At this mental crossroad, I paused and inhaled; my thoughts raced: What does she mean by “my people?” Fellow Quakers? My family members? Humans who fall under the socially constructed notion of black? Is she arguing that savior-centered propaganda that all abolitionists were of European descent? Exhaling, I had limited options in how to reply politely to the direct assault of the manifestation of stereotypes about blacks and spirituality, and her indirect implication that although seeming to appreciate my presence and presentation, I was still an interloper who had to have an external rationale for my Quakerism.

My very presence had unintended consequences; it made the visitor question and interrogate her stereotypes about Quakerism, race, and the categorization of people. By her employment of the matter of race, my black presence, in that presumably socially imaged white Quaker space, became a confounding variable for her. She, unwittingly or wittingly, easily fell into the matrix of interrogation and deputized herself to police and understand how and why I was there. Perhaps not knowing that her line of questioning stemmed from a white-supremacist tinged culture, she expected me to allay her unarticulated anxiety, fears, and expectations of why I did not fall into her neat understanding of identities associated with Quakerism and race.

In the stifling miasma rooted in the fascination with race and adhering conversations about how race should not matter, people described as “of color”—as if white is not a color and such language does not privilege white as normative—must ingratiate themselves to uninvited discourse and be willing to offer a litany, praise, or lamentation of why they exist, or they must decriminalize unarticulated stereotypes about their humanity. The very presumption that we must, and should desire to, stand in the gap to offer rationales to such queries underscores why the tenets of Quakerism congeal with my being.

A deep-rooted tenet of Hicksite Quakerism is that people are guided by the Inner Light. In the presence of the Inner Light, my humanity is not contested, vilified, praised, and questioned. In the presence of the Inner Light, I do not have to perform an identity. The sum of my being is not that I am descendent of a race once described as chattel and commodified to such a degree that notions of white supremacy denied them the traits associated with humans, such as intelligence, keenness, ambition, belligerence, enterprise, and indifference. In the Inner Light, I am not disinherited from humanity, and I am not socially inferior.

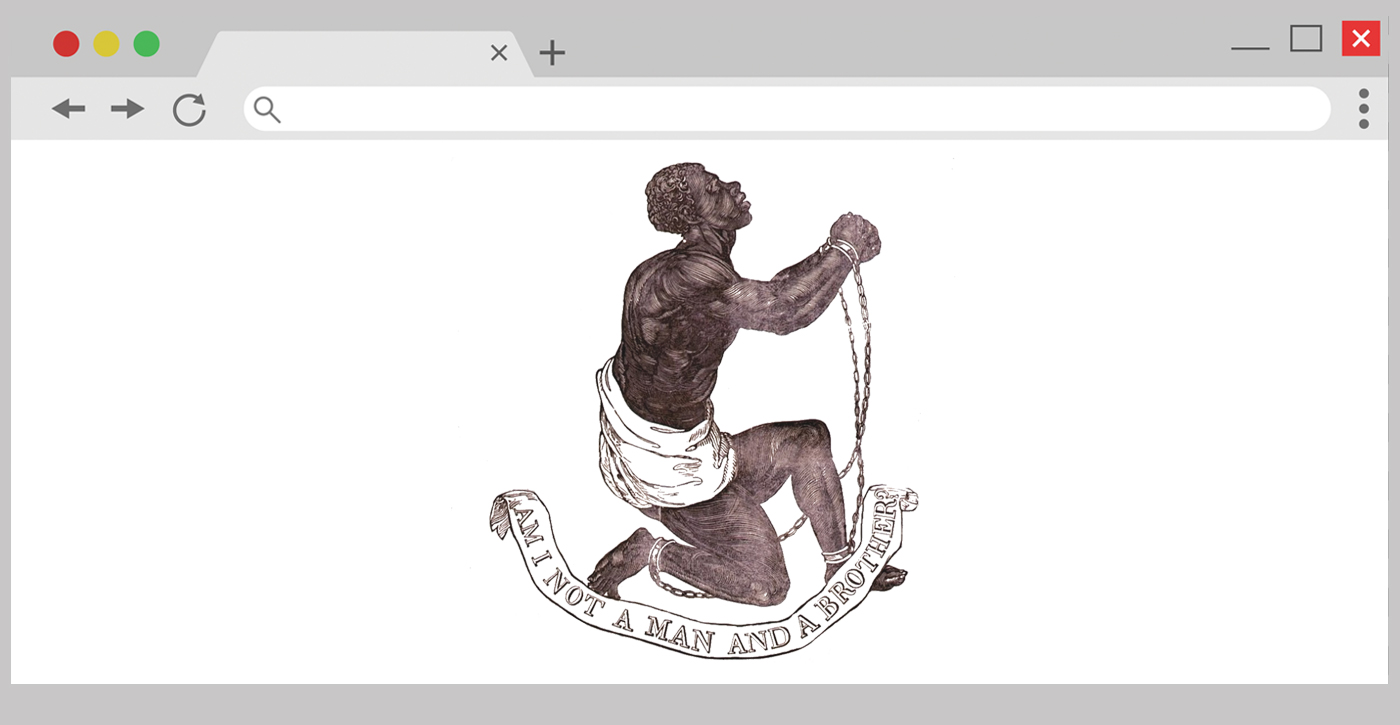

The transformative waiting on the Inner Light offers liberty and freedom. Influenced by his grandmother and Quaker mystic Rufus Jones, theologian Howard Thurman shared in his 1949 book, Jesus and the Disinherited, a sermon from an enslaved preacher that rooted in my spirit. He explained that as a slave, his grandmother annually heard an enslaved preacher proclaim: “You—you are not niggers. You—you are not slaves. You are God’s children.” Reading those words in Quaker service transformed me because, like Thurman, I too focus on the reality that the Creator of existence created me, not how well I perform race. The legacy chains of bondage broke immediately with the Inner Light. Delineated rules and lines, steeped in racial traditions, are erased because the idol of white supremacy topples in the awe of the guidance of the Inner Light.

My relationship with the Inner Light and the tenets of Quakerism allows me to be a quintessential dissident to notions of hierarchy, supremacy, segregationist politics, paternalism, maternalism, and materialism. In the Inner Light, “The Lord is my shepherd” (Psalm 23:1). Fear of being judged or misjudged dissipate daily.

One of my favorite parables in the Holy Bible is found in Matthew 25:14–30, and it is about talents. A king decides to go on a journey. Yet, before he departs, he doles talents to three servants, based on individual abilities. To one servant, he gives five. To another, he gives two. And, to the last one, he gives one. The king departs. The first two servants immediately go to work and earn returns. The last servant—the one with the one talent—digs a hole in the ground and places the talent there. After some time, the king returns, summons the servants, and requests a status report. The first two explain that they have doubled their talents—the one with five now has ten, the one with two now has four. The king calls them “good and faithful” servants and rewards them. The last servant offered the king the same coin that the king had given him. Rendering himself a victim of the possible ire and power of the king, the last servant explained to the king that he knew that the king was a mean man, so he buried the coin in the ground so he would not lose it. The king was livid. As the king admitted that he was surely an exploiter, he still told the servant that he should have put his money in the bank, so it could gain interest. He orders that the talent be given to the servant with ten and then casts the last servant into the abyss.

The parable resonates in my life because, if not careful, a nonwhite human can spend a lifetime answering and refuting the catcalls of stereotypes spawned by the ideology of white supremacy and not developing the talent she possesses.

Ultimately, what mediation in and guidance of the Inner Light have helped me determine is that performing radicalized gender expectations was not my purpose in life. In this way, the tenets found in Quakerism liberated me from the juggernaut of supremacist politics. When I encounter intentional or unintentional bigotry, I settle and remain focused on what the Inner Light has for me. In this way, the Inner Light creates the transcending atmosphere that may allow a person with inward understanding to nurture a politic that radically and outwardly helps transform the world because one is transformed daily. In a world of consumer-tainted self-worth, it is revolutionary for one to know that “I am” and “I am enough” from within.

The Inner Light allows the narrative to reign so an internal movement may agitate. A public or private abolitionist movement demands that an internal sense of worth and significance does not derive from external environments. Take for example, the life of freeborn, Quaker-educated abolitionist and Canadian emigrationist Mary Ann Shadd Cary. In the mid-nineteenth century, she advocated in opposition to the reduction of blacks to beggars of the benevolence of whites. With her editorials in the newspaper she co-founded, the Provincial Freeman, the schoolteacher and journalist found herself at odds with members of all hues when she stressed self-reliance. I suspect that the success of her landowning, abolitionist father, Abraham, and her experience with Quaker education contributed to her willingness to speak boldly, even if it meant alienation. Her life illustrates one led by the Inner Light that she undoubtedly heard of in her interactions, albeit probably not always enlightened exchanges, with Quakers. An ally to Shadd Cary, Quaker-educated abolitionist Samuel Ringgold Ward ruefully argued about Quakers: “They will give us good advice. . . . Whatever they do for us [blacks] savors of pity, and is done at arm’s length” (as quoted in Black Abolitionists by Benjamin Quarles, 1969).

Discourse among Quakers is often uplifting and flattering, but it may not always result in affirming interactions. Yet, as a Friend who is nonwhite, I make no assumptions that I am free from work, and I pray all Friends realize that continuous work must be done to create parity and to render insolvent race-based spirituality. We bind in love, abolition of hatred, and wellsprings of hope.

I am STUNNED. Ashamed and stunned. THIS is NOT very welcoming, supportive Quaker treatment. What happened to “there is that of God in every person”?

Cannot even finish.

Thames Taylor thoughtfully states what need to be said. It is sad that we (whites) believe we have the right to question someone’s humanity and space, even in Quaker spaces. I have done this a few times myself, but after reading this article, I will speak with caution because I know my words are tainted by my privilege.