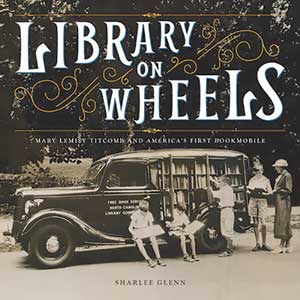

Library on Wheels: Mary Lemist Titcomb and America’s First Bookmobile

Reviewed by Margaret T. Walden

May 1, 2019

By Sharlee Glenn. Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2018. 56 pages. $18.99/hardcover; $15.54/eBook. Recommended for ages 8–12.

By Sharlee Glenn. Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2018. 56 pages. $18.99/hardcover; $15.54/eBook. Recommended for ages 8–12.

Mary Titcomb was a girl with determination; she wanted to be a person who made things happen. Born into a poor farm family in New Hampshire, Mary watched as her two brothers went to Phillips Exeter Academy for a good education. She and her sister begged to be allowed to attend school beyond eighth grade. Her parents agreed, and both girls studied at the new Robinson Female Seminary. As her brothers began to choose careers and leave home, Mary looked around for her chance to also accomplish something with her life.

In the 1870s, public libraries were very new, but reading and sharing books seemed just right. There was an apprenticeship in Concord, Mass., and making it safe for her in that era, her brother George moved to Concord and set up his medical office. In her new unpaid job, Mary delved into all that she could learn about cataloging, acquisitions, binding, and administration. A move to Vermont’s Rutland Free Library came next. She had begun her career! There was a setback when Mary’s request for a position at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition was turned down by Melvil Dewey on the grounds that she was not a nationally known librarian.

She had many obstacles to overcome in her desire to excel in her profession. It was a man’s world in the nineteenth century. Some people needed to be convinced that libraries were important—even central—to a democratic society. Mary, now known more formally as Miss Titcomb, was elected to the Vermont Library Commission. Even the famous Melvil Dewey had to take notice now.

Having noticed the growth of libraries in New England, Edward W. Mealey of Hagerstown, Md., raised money to erect a public library building. When he looked for a trained librarian to run their new library, he found Miss Titcomb. Her family thought it was unwise for her to leave her secure position in Vermont for the unknown region of rural Maryland, but Mary could not resist the challenge. In 1901 she arrived in Hagerstown and had six months to set up and open the new free county library, only the second in the country. Would local people come? Did they care about books and knowledge as she did? Would the children like their own special book room?

Opening day was a huge success, which pleased the library board, but Miss Titcomb noticed that the country folk in Washington County were not participating. How could she serve the half of county residents that lived outside the city? Skeptics said that farm families had no time or desire for books or reading, but Mary took up that challenge.

Miss Titcomb stayed in Hagerstown for the rest of her career. She made many innovations over the years, working hard to convince the library board to fund her plans. There were soon children’s story hours throughout the county and book deposit boxes in grocery stores, post offices, and even front porches. But her most remembered—and loved—idea was the first book wagon in the United States. Horse-drawn in 1905, it was soon replaced by a motorized version. Public libraries still have bookmobiles and delivery trucks to this day, and it was Miss Titcomb’s perseverance and imagination that made bookmobiles happen.

Sharlee Glenn combines biography and history for a detailed look at the rise of public libraries in turn-of-the-century America. A wealth of information is packed into 56 pages. Notes and bibliography direct the reader where to look further. All is presented using archival photographs and a scrapbook style that pulls one into the life of rural Maryland in the early 1900s. This is a beautiful book that will tempt all ages.

Here is another possibility for “What will I do when I grow up?” There are certainly many Quaker librarians, because librarians serve people, as do social workers, teachers, doctors, and scientists. Their work is crucial to the preservation of democracy. I like that the author does not talk down to her young audience. She describes some of the difficulties that a forward-thinking career woman confronted with help from family and friends. First-day school children sometimes interview local heroes—people in their own meetings—about their life paths. The story of Mary Titcomb, although she was not a Quaker, could be the start of such a unit, helping with ideas for interview questions.

This was one small part of library history, but in 1900 it represented the modern world. The current, much larger county library in Hagerstown, Md., displays this motto: “Where people and possibilities meet.” Miss Titcomb would approve.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.