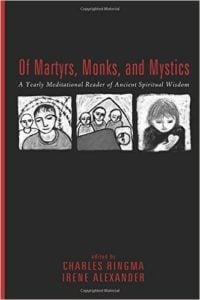

Of Martyrs, Monks, and Mystics: A Yearly Meditational Reader of Ancient Spiritual Wisdom

Reviewed by William Shetter

June 1, 2016

Edited by Charles Ringma and Irene Alexander. Cascade Books, 2015. 440 pages. $48/paperback or eBook.

Edited by Charles Ringma and Irene Alexander. Cascade Books, 2015. 440 pages. $48/paperback or eBook.

Buy on QuakerBooks

Since this book offers a one-page quote for each day of the year, the editors could have with equal justice called it “a daily meditational reader.” Each day’s page starts with a Bible reference (the greatest number of them from the Book of Psalms), then an extended quote from one of over 90 different ancient authors, and at the bottom of the page is a brief concluding meditation variously labeled “Meditation,” “Thought,” “Prayer,” or “Reflection.” The editors’ vision is an admirably ambitious one: they offer us a small sample from “the deep wells of theological and spiritual insight,” and in their introduction remind us that “these voices speak of a recovery of spirit, the need for the re-enchantment of the modern world, focus on the growth of wisdom . . . and the need for a reengagement with meditative and contemplative practices.” They invite the reader to “explore some of the ways in which the ancient wisdom can bring light to our contemporary spirituality.”

These writings are from 14 centuries of Christian living, from Clement of Rome of the first century, to Catherine of Genoa, who died in 1510 CE. They are the reflections of medieval mystics, early desert fathers and mothers, early martyrs and saints, and those part of the long monastic tradition. The three authors most often quoted are Saint Francis (thirteenth century), Saint Augustine (fifth century), and Julian of Norwich (fourteenth century). Although not all their thoughts—for example those on the Trinity, Baptism, the Eucharist—will speak equally persuasively to Friends, readers may be surprised to note how old, and therefore deeply rooted, many of our most valued spiritual treasures are.

Some of the early Desert Fathers urge us to celebrate the beauty surrounding us. The importance of discernment is prominent in the thought of Gregory of Nyssa (fourth century), John Cassian (fifth century), and Columbanus (seventh century). In the fourteenth century, Meister Eckhart’s thoughts revolve around the balance of contemplation and action, the identification of love as profound respect, the fruitfulness of the spiritual life, and the reality of God’s presence in all things. He is joined by many others through the centuries in meditating on the light of Christ. Our attention is called to the centrality of an attitude of humility by Bonaventure, The Cloud of Unknowing, and others. The eleventh-century archbishop of Canterbury Anselm offers some powerful words about what forgiveness holds for both receiver and giver. An Irish poet of the fifteenth century reminds us of the importance of a deeper listening, and our familiar metaphor of the “spiritual journey” appears to be just as familiar to even the earliest writers. The Scot Richard of Saint Victor (twelfth century) is thrilled—and inspires the reader of today—by the power of simple wonder at all that is around us.

Such resonant insights as these are examples of what the editors mean by “the re-enchantment of the modern world.” Friends will feel even more at home in the meditations of many of these ancient authors, such as Gregory the Great (sixth century) on the Inner Light and the English mystic Walter Hilton (fourteenth century) on God within. Many authors, such as Saint Basil (fourth century) and Bonaventure (thirteenth century) write about the central importance of silence. In the fourteenth century both Catherine of Siena and Julian of Norwich reflect on the inner voice, the inner promptings of the Spirit. Abbot Symeon, the eleventh-century Byzantine mystic, reaches across the centuries to remind us how far back our mystic tradition reaches. The fourth-century bishop of Constantinople John Chrysostom shows a modern-sounding environmental awareness when he evokes the power and beauty of Nature. For both Origen (third century) and Francis of Assisi a thousand years later, true wisdom comes from what we would now call “experiential living.” Our commitment to patient waiting for the Spirit to speak differs little from the words of Hadewijch in the thirteenth century, and we hear our testimony of equality being given a strong voice in The Cloud of Unknowing. We can feel quite familiar with the words of Hildegard of Bingen (twelfth century) that “each human being contains heaven and earth and all of creation.”

We can feel heartened and reassured on finding here much of the depth of the fertile soil which today continues to nourish our own faith.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.