The north windows are at my back, and the south windows are in front of me. I’m sitting at a long library table at Beacon Hill Friends House in Boston. What an unexpected delight to be in this library and in this very old house with the very old books!

Across the Boston Common and down a few streets to Chestnut, this historic house was built during the early 1800s. It is November. The street is lined with trees, now bare. The sidewalk is bumpy because of tree roots trying to push through the bricks. There was once talk of replacing the bricks with a regular sidewalk, but the citizens fought against it; they wanted to keep the ambiance of the past.

Twenty residents live here in this mansion-like house with balconies and spiral staircases. There are several guestrooms, and I am staying in one of them. I had come to Boston to see two young men who, in New York where I live, had been in immigration detention, seeking asylum. Their names were none other than Joshua and Moses! Joshua was from Sierra Leone and Moses from Cameroon. A Quaker friend arranged for me to stay here.

When the director showed the library to me, I was eager for a chance to explore. Later, when time permitted, I looked around for the right stairway. I should have paid closer attention. Now which one was it, and on which floor?

Given to imagination, I am reminded of stories where the heroine finds herself in a mysterious castle of innumerable rooms. Getting lost going down hallways, she hears footsteps and strange noises, and comes upon hidden secrets. This house isn’t that large, but I did hear footsteps because the house creaks with the weight of the centuries.

Most of the residents are gone for Thanksgiving, but I found a girl in the kitchen who gladly showed me the way. Nimbly, she flew up the stairs and flung open the library door.

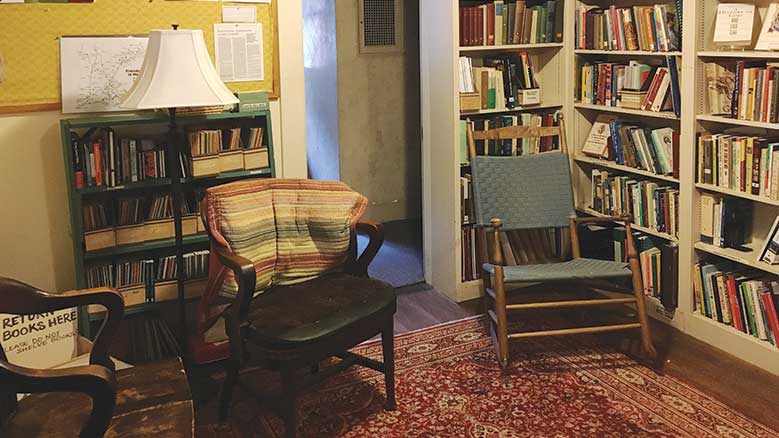

I look about me. Books from floor to ceiling—age-old books. Even if I stood on a chair, I could not reach the highest ones. The walls are lined with them, even over the doors. There are two fireplaces. In between the fireplaces is an armoire. I open the doors. Inside I discover the oldest of books and pamphlets. I pick up one pamphlet. Brittle and yellow, its date is 1830.

Closing the armoire and looking at the bookshelves, I find my attention drawn to the book Five Present-Day Controversies by Charles E. Jefferson. The copyright is 1924. Wondering what controversies might have raged back then, I pull the book out. I open at random and read:

The mind of the average man today is confused. That is because we are living in a hurry. We have no time to listen to anything through, or to read anything through, or to think anything through. We have a multitude of counselors, and the air is filled with voices, which are saying things. We snatch up a sentence today, and another one tomorrow, and we have no time to put the two sentences together. The world is flooded with papers and magazines and books.

I think that this certainly sounds like now. People jump to conclusions and don’t take time to listen or to see the whole picture. They snatch a sentence here and a sentence there and make judgments. There’s no time for reflection. I think of a recent jarring experience of my own. I flip over a few pages and continue:

And where are we to look for relief? Certainly not to the national government. There is no balm in that Gilead. Our government is so constructed that a little company of foolish and stubborn men can tie it into a hard knot, so that democracy is incapable of functioning at all. The national government is paralyzed again and again by the spirit of partisanship. . . .

We cannot go to our churches. The churches are numerous and active, but they are unable to focus their moral forces on the spot where it is most needed. We have all sorts of organizations created for numberless good purposes.

Well, this sounds very current. I flip over a number of pages: “You cannot argue with men who are afraid. Under the spell of fear men will do all sorts of foolish things.”

I ponder the turn of phrase: “Under the spell of fear men will do all sorts of foolish things.”

I think that this certainly sounds like now. People jump to conclusions and don’t take time to listen or to see the whole picture. There’s no time for reflection.

Some time ago a book came into my hands, Dancing with God Through the Storm: Mysticism and Mental Illness, written by Jennifer Elam, also a Quaker. I identify with the title because of many times I have “danced with God in the storm.” I was especially interested in Jennifer’s book since, when I met her for the first time at Quaker meeting, she told me that an early writing of mine about mental illness, They That Sow in Tears, had been the means of her getting a grant to write her book.

In that book, she quotes a very prolific Quaker writer, Rufus Jones (1853–1948):

The mystic has a constitution, which by nature is in danger of disintegration and dissociation. He is threatened with excessive centrifugal tendencies. Parts of his being are inclined to run off and do business on their own hook. It is essential for him, therefore, to become integrated, knit up into a coherent whole. Just the work of unification is what is usually wrought by his discovery of God. His mighty conviction tends to bind his life into a well-organized system. The divided self becomes unified. George Fox is an excellent illustration of the cohesive power of a great experience of God. It turned his darkness into light, his sadness into joy, his despair into hope, and under its influence his poor distraught mind seized upon and held to a constructive central purpose. At the same time, the whole creation seemed to him to be transfigured, “new-molded,” and penetrated with a “new smell.”

Jennifer comments:

Seventy-five years ago, Jones was struggling with a community of people who were willing to see pathology where he believed none existed. So when there was stigma, Jones turned it around and noted that if mystical experience makes one abnormal, then he would be proud to be among the “abnormals.” In fact, he redefined as abnormal anyone who did not glory in the presence of God. He described the “essential human soul in the presence of the august, majestic, mysterious, awe-inspiring realities,” which produce a consciousness of what he calls the “numinous.” Jones says, “You either have it or you do not have it.”

I thought that this man would have understood and appreciated my experiences and come to my defense.

I pick up one of Jones’s books, Quakerism: A Spiritual Movement:

As soon as religion has closed up “the soul’s east window of divine surprise,” and is turned into a mechanism of habit, custom, and system, it is killed. Religion thus grows formal and mechanical, though it may still have a disciplinary function in society. . . . The spring of joy, which characterizes true religion, has disappeared. . . . It is live religion only so long as it issues from the center of personal consciousness and has the throb of personal experience in it.

In the chairs no visible person sits, but I am among Friends “and they being dead, yet speak.”

One summer over 20 years ago, I was visiting a friend in Wenatchee, Washington. During the day she had to go to work. To occupy myself, I looked at the books in her bookcase and picked one out: Biographies of Great Christians. This is when I first discovered George Fox.

Perhaps no other small group of people has so influenced the world for good as the Quakers. On many questions, they were far in advance of their times, being pioneers against slavery, and for women’s ministry and religious liberty. All of these achievements came forth despite (or perhaps, because of) the challenges Fox faced.

He was much concerned about social justice issues, such as the conditions in prisons. Regarding war he said, “I told them I lived in the virtue of that life and power that took away the occasion of all wars.”

In his Journal, Fox records experiences which, if there had been a modern psychiatrist present, he or she most likely would have taken these experiences as signs of psychosis. As an example, one such entry in Fox’s Journal reads:

And as I was one time walking in a close with several Friends I lifted up my head and I espied three steeplehouse spires. They struck at my life and I asked Friends what they were, and they said, Lichfield. The word of the Lord came to me thither I might go, so I bid friends that were with me walk into the house from me; and they did and as soon as they were gone (for I said nothing to them whither I would go) I went over hedge and ditch till I came within a mile of Lichfield. When I came into a great field where there were shepherds keeping their sheep, I was commanded of the Lord to pull off my shoes of a sudden; and I stood still, and the word of the Lord was like a fire in me; and being winter, I untied my shoes and put them off; and when I had done I was commanded to give them to the shepherds and was to charge them to let no one have them except they paid for them. And the poor shepherds trembled and were astonished.

So I went about a mile till I came into the town, and as soon as I came within the town the word of the Lord came unto me to cry, ‘Woe unto the bloody city of Lichfield!’ . . . Being market day I went into the market place and went up and down in several places of it and made stands, crying, ‘Woe unto the bloody city of Lichfield!’, and no one touched me nor laid hands on me. As I went down the town there ran like a channel of blood down the streets, and the market place was like a pool of blood.

And so at last some friends and friendly people came to me and said, ‘Alack George! Where are thy shoes?’ and I told them it was no matter; so when I had declared what was upon me and cleared myself, I came out of the town in peace about a mile to the shepherds: and there I went to them and took my shoes and gave them some money, but the fire of the Lord was so in my feet and all over me that I did not matter to put my shoes on any more and was at a stand whether I should or no till I felt freedom from the Lord so to do.

And so at last I came to a ditch and washed my feet and put on my shoes; and when I had done, I considered why I should go and cry against that city and call it a bloody city;But after, I came to see that there were a thousand martyrs in Lichfield in the Emperor Diocletian’s time. And so I must go in my stockings through the channel of their blood in their market place. So I might raise up the blood of those martyrs that had been shed and lay cold in their streets, which had been shed above a thousand years before. So the sense of this blood was upon me, for which I obeyed the word of the Lord. And the ancient record will testify how many suffered there. (Nickalls, ed. Journal, 71–72)

What if the world had been robbed of the Quakers and all the good they did? Think of John Woolman, William Penn, and Lucretia Mott—just a few of the many Quakers who were inspired by Fox. I can’t help but feel that psychiatric medications and labels are robbing the world of people with similar gifts. I meet people who stand out and seem to have this calling. They express a sense of mission and feel they have heard from God. If they are artists and draw pictures of burning bushes, is this just “religious preoccupation”? Should all of this be passed off as symptoms of mental illness? Should they be considered well if they stop talking about God?

With the 9/11 report, we’ve heard much of CIA intelligence failures and the need for accurate information. We’ve read of the extreme lengths to which officials have gone to get this information—even torture in disregard of the Geneva Convention. Are we, as a nation, bypassing and psychiatrically labeling the answers to the information we need?

I look around the large room of this library with the silent books giving testimony. There are large green plants, chairs, tables, and lamps along the walls. In the chairs no visible person sits, but I am among Friends “and they being dead, yet speak.”

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.