In September, a workshop resembling a Quaker meeting with stethoscopes and rhythm instruments was enacted at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Alberta, Canada, lead by composer and rock musician Richard Reed Parry of Arcade Fire fame. I was struck by the braveness of Parry’s presentation; it is not usual for musicians to share spiritual outlook with one another, and unheard of to openly share practice and meaning.

Parry is the composer of Music for Heart and Breath, an album conceived of at the Banff Centre that has received substantial acclaim for its unusual beauty. Forthright about the Quaker origin of the piece, Parry, who was raised Quaker, set out to create a composition for strings and piano that captured heartbeat rate and breath speed as rhythmic dictators of tone and timing. The result is a shimmering breath-scape of shifting tone colors supported by the insistent presence of performers’ heartbeats imposed on a purposeful meditative environment. It is both moving and wondrous.

The Banff performance of Music for Heart and Breath and Parry’s workshop were part of a weekend residency called the Art of Stillness and attended by 18 artists in four disciplines. Parry appeared as leader of the music section. He was surrounded by some legendary colleagues; the leader of the writers was Pico Iyer; of dancers, Christopher House; of artists, Diane Borsato. This luminous crew led discussions, movement classes, lectures, workshops, and individual appointments with participants in any of the disciplines. Parry allowed his compositions to be performed by an expanded ensemble of players of varying skill levels, encouraging and guiding the musicians toward comfort in approaching the unique style while requesting very accurate interpretation of his scores.

Parry’s workshop version of Music for Heart and Breath included his opening of an orange suitcase of stethoscopes after seducing his audience into a state of very present quiet. He created this settled atmosphere by allowing participants to enter the room while two violinists softly played the rhythm of their own heartbeats; it was apparent that each violinist’s heartbeat increased in speed and then slowed during the entrance and seating of each participant. After sitting quietly for several minutes, Parry described the process of expectant waiting, explaining that the workshop would introduce the compositional elements used as organizing features in his music. He distributed stethoscopes and encouraged everyone to begin listening to their own heartbeat. To allow for more audible expression, Parry distributed woodblocks and finger symbols to create an improvisation sparked by his compositions. He designed a shaped counting scheme for creating a slow rise and ebb of improvised sound based on each person’s heartbeat, leading to a noticeably awoken atmosphere of listening, careful waiting and spiritual presence in the room.

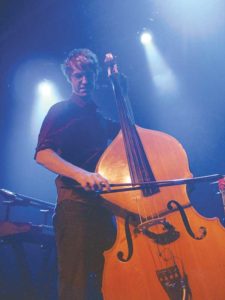

Later in the week, Parry performed a full evening concert of Music for Heart and Breath, in the beautiful Rolston Recital Hall at the Banff Centre. One of the most effective pieces of the concert was Parry’s “Heart and Breath Sextet” performed by six hands at the piano (two of them Parry’s) and three string players. Parry wrote for these players in a somewhat antiphonal way, juxtaposing moments of extremely delicate string harmonics with warmer sections of rhapsodic piano minimalism; it is a haunting work and the performers accomplished the tracking of their heartbeat and breath with maximum confidence and independence. “Duet for Heart and Breath,” with Parry at the string bass and Pemi Paull at the viola, was extremely moving, partly because the two performers moved so seamlessly between listening to their own bodies and connecting musically with one another.

The logistics of tracking a performer’s heartbeat throughout an entire concert is interesting. Once a musician found a reliable placement for her stethoscope, she wrapped a long elastic bandage around her chest, trapping the stethoscope at the right place for the optimal hearing of her own heartbeat. Some musicians secured their stethoscopes with surgical tape. The addition of these items seemed to be the perfect medical accompaniments to the monitoring of heartbeat; the dress rehearsal was enlivened by the performers assisting one another in securing their devices, sometimes searching for a stethoscope with a more sensitive diaphragm or lamenting the lack of Velcro on the elastic bandages. Within the performance, performers often removed one ear piece so they could hear one another better, sometimes allowing the ear pieces and tubing to hang down their back if they weren’t needed for a particular movement.

Audience response to the concert was overall very positive. Despite the noisy abdication by a few people making unnecessarily hasty exits, the performance was met with interest and respect. There was a quasi-meditative atmosphere produced: a receptivity and appreciation for the music that reflected the interest in Parry’s musical work, whether in rock or new music. Parry has tapped into a deep and intimate place for listeners, creating an aesthetic that acknowledges individuals while mining collective possibility. His work can be deeply engaging for the audience; one artist in Banff said the music triggered too much fear in her, reminding her of being in the MRI machine when she was treated for breast cancer.

The Art of Stillness residency offered a special opportunity for artists to learn about one another’s creative process when new pieces were developed on site. Premiering “Breath, For Voice and Strings” was a chance to see how Parry creates. He is extremely humble and open to suggestions by performers when creating a work, asking for immediate feedback on nearly any aspect of the piece. When I remarked to him how I unusual I found this, he replied that it was normal for rock musicians to seek out responses from fellow band members and to be ready to accept other musicians’ ideas. His approach is refreshing, open, and effective, and it is clear that Parry surrounds himself with outstanding musicians. The Banff project was enriched by the attendance of Toronto violist Pemi Paull and Berlin violinist Ayumi Paul, both of whom had worked with Parry previously but had not met before the Banff program.

As a singer, I initially found it difficult to sing Parry’s work, because it seemed to be formed of many starts or initiations of long sound extended through bodily possibility rather than artistic decision. Even as a regular practitioner of unmetered chant, I was very aware that truly allowing tone to be driven by the physical limit of exhalation is different than the production of a note with a planned length. This is particularly true if the emittance of the tone is devoid of the shaping determined by emotional intention or conscious reflection of meaning. Repetition of pitch sequences without conscious rhetorical purpose was challenging for me, particularly as Parry’s “Breath” piece had no text. The creation of his new piece allowed me to have a true immersion in Parry’s work; I was able to listen to the entire concert and went on stage only to appear in the premier of Parry’s new vocal work.

The result of sitting through the rehearsals, dress rehearsal, and concert of Parry’s music was that my breath feels permanently slowed, calmed, even somehow tamed by the experience. I find myself breathing lower, slower, deeper, longer, fuller than ever before. In the end, I found Parry’s music radiant and elevating, surely a worthy performance goal. Carrying one’s spiritual legacy successfully into a professional artistic environment is a welcome and radical act; Parry created a moment of insistent connection between the players, listeners, and beyond.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.