My fear is that we are in the final chapters of Quakerism. A number of years ago, I was stunned to read a report by Mark Myers, who was then general secretary of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (PhYM). The report stated that PhYM’s membership was graying with 45 percent of members over the age of 60. Moreover, the total yearly meeting membership, which counts Friends living in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, including the Greater Philadelphia area (considered to be the bastion of American Quakerism thanks to the city’s founder, William Penn), had declined nearly 25 percent in the past three decades. By any standard, these facts seemed discouraging. Could anything be done to reverse this trend?

Of course this question has been considered many times before. One can imagine numerous Quaker committees pondering the issue of membership and attrition. I am no expert on religious communities, so I consulted with others. It was suggested that perhaps it was not so bad. Perhaps meetings had “purged their rolls,” and the smaller numbers were more representative of “true membership.” Others suggested that organized religion in general was on the wane. Yet, as I looked around my own meeting and others that I visited, these explanations seemed insufficient. Meetings seemed tired, empty, and listless. It was within this context (in the summer of 2013) that I fell upon the notion of a Quaker passage ceremony for my up-and-coming 13-year-old Quaker son.

It seemed obvious that the antidote for an aging group is younger people. However, the truth is we had no grand vision when we decided upon a passage ceremony for our son, Aaron. There was no notion of such a ceremony being more widely used within the Religious Society of Friends. My wife and I were not then thinking about the absence of adolescents in our larger Quaker world. At that time, we were only thinking about Aaron, his needs, and the needs of his community. The idea of writing about this and offering it to the larger society came much later, after our own ceremony was complete. In talking with Friends and reflecting on the success of this ceremony, I decided to write about it.

As a lifelong Friend, I have always cherished two wonderful Quaker ceremonies: weddings and funerals. With silent worship, awaiting the Light, and being community-led, these ceremonies have been beautiful beyond words. For me, they are far more personal than the practices of other faiths. In the wedding ceremony, Friends rise from silent worship to speak to the couple about to wed. During a funeral, Friends who may have known the deceased for a lifetime rise to share thoughts, feelings, and energy—very personal reflections. These rituals are so powerful and alive, and each event is unique. Why, I wondered, couldn’t we offer the same to our youth? Why should this type of powerful community ceremony be limited to marrying couples and honoring those who have died? That framework left out the crucial phase of adolescence—the beginning of adulthood. If we left out adolescents from our rituals, it was no wonder that our numbers were declining. Adolescents are not only the age group that we need, but they need us. From many meetings, the report was the same: as soon as children entered adolescence, they left our midst.

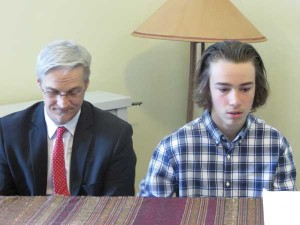

Aaron’s ceremony could not have been simpler. It was held in the meetinghouse of our meeting, Wilmington (Del.) Meeting. There were fewer than 40 people in attendance. His friends, grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and neighbors attended, as well as some of his teachers. Most were Quakers, but some were not. All understood, however, the tradition of silent worship. Many strong messages were given to him that day. One was that you are important to us, and we need you. It was both implied and stated outright that the community would be there for him. It was equally clear that his community had expectations of him, that he as a unique person was needed. Not only his parents were talking, his entire community was saying this. At the end, he was given a bound book with personal messages, which he will have his whole life. What better start could there be for one who is venturing out into the turbulent waters of adolescence?

I will end on a somewhat political note. There is violence and strife in the world, and we are concerned about fanaticism and hatred. Often violence is done by those who claim to be acting in the name of God. In Acts of Faith, author Eboo Patel, an American Muslim scholar, points out that fanatics don’t miss a beat when it comes to engaging youth. Fanatics and messengers of hate send a clear message to young men and women: “We need you. You are special. You have a mission from God. Join us.” Fanatics put youth first and foremost. They recognize how crucial the energy of youth is, and they are experts at engaging youth. Should our Quaker message to our children be any less? If it is, perhaps we yield our faith and the world along with it. Perhaps a small step of instituting passage ceremonies is a way to begin rebuilding.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.