Sixty-two fourth-grade students from Hyattsville Elementary School in Maryland file in, slowly moving down the center aisle where Quakers have trod for over 200 years. Passing row after row of worn-smooth wooden benches, each step takes them deeper into the worship space at Philadelphia’s Arch Street Meeting House. The young visitors sit down near the front of the room, their feet swaying inches from the unfinished pine floor.

After welcoming the group, a trained volunteer docent makes Quaker guiding principles relevant and real through interpretation, interaction, and education.

“By show of hands how many of you have been to a meetinghouse before? What about a church? Synagogue? A mosque? Great! Now take a look around this room. Think about how this room is different from other churches or worship spaces you have been to. Who can tell me what they see that is different?”

“There is no cross.” “My church has a stage up front for the priest to stand on while he talks.” “We have candles and Bibles and an organ, but you have no organ.” “No colorful windows here.”

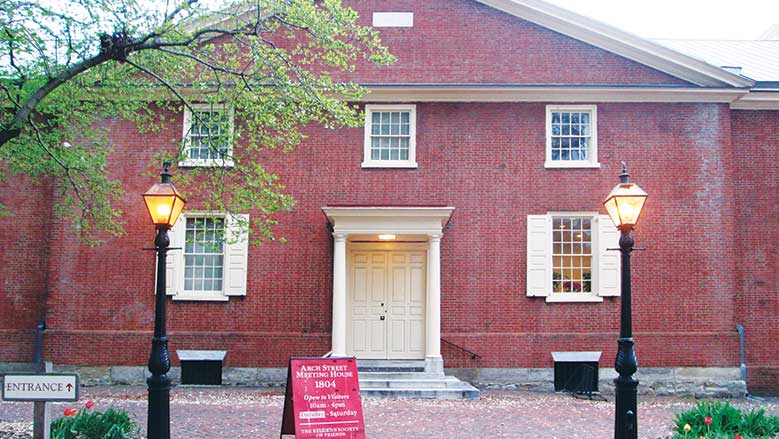

This is a snippet of one of the new activities we have developed and are in the process of testing at Arch Street Meeting House. Many local Friends are familiar with the meetinghouse and know it as a vibrant hub of Quaker activities, but few know that it is also one of the nation’s most visited Quaker historic sites. As a National Historic Landmark located in the heart of tourist-town Philadelphia, it’s a place where the public can learn more about Quakers. Due to its location, surrounded by other popular historic sites open to the public, tourists turn the doorknob seven days a week and ask for a glimpse of what’s inside. The doors have been open to the public for nearly a century, and each year more than 25,000 visitors come to Arch Street Meeting House from all around the world to learn more about Quaker history.

Drawing us to stories

I am a Quaker because of history. For as long as I can remember, I have been drawn to the stories of people who do good for the sake of doing good. Few reading this article are likely to be surprised at how often those who do good for the sake of doing good end up having connections to Quakerism: women’s suffrage, Quakers; abolition, Quakers; Native American rights, Quakers; work on behalf of the environment, Quakers. Page after page and chapter after chapter in my history textbooks told inspirational stories of the big impact Quakers have had on the founding of the nation.

Public historians, as opposed to academic historians, work with and for the general public in places such as museums, archives, and historical societies. The idea of being able to make a living while engaging with history in this way appealed to me. During my graduate studies, I took classes focused on the rigors of academic history as well as museum studies, tourism, nonprofit management, and historic preservation. As luck would have it, I was assigned an advisor who I later learned was a Quaker historian. She was perfectly placed in my life to teach me how to analyze the records of the Religious Society of Friends, which deepened my understanding of the culture and legacy of Quakers.

For the last three years serving Quakers and the public in my role as director of Arch Street Meeting House, I have been able to call upon my academic interests and professional training on a daily basis. This work is personal and meaningful to me, and I’m glad to have the opportunity to share more about Quaker history and beliefs with the general public.

Repurposing our shrinking congregations

As church attendance drops and worship communities across the United States shrink, many places of worship, both historic and modern, are losing their resource base. It becomes difficult for shrinking congregations to manage and maintain large buildings. Although it is still home to an active worship community, Arch Street Meeting House was built to such an immense scale in 1804 to accommodate the throngs of Quakers who traveled to Philadelphia once a year for a weeklong event known as Annual Sessions. Now that the meetinghouse is no longer used as the site of Annual Sessions, it is time for Arch Street Meeting House to assume a new identity, one that will continue to reinforce its relevance on days other than Sunday, in a way that benefits people of all faiths or even of no faith.

It is hard for me to ignore the fact that other historic sites in this tourist-destination neighborhood welcome 250,000-plus visitors a year. Almost every day long lines of people can be spotted waiting to see the Liberty Bell and spiraling through Independence Mall. I think about ways to reach them. Arch Street Meeting House has begun to reflect on its public programs and consider different approaches to further engage the audience of heritage tourists and school groups that walk past the front gate. How can we encourage tourists to walk through the doorway of an unfamiliar religious building when they have traveled to the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia expecting history?

Over the last few years I have struggled with the question of how passers-by on their way to the Betsy Ross House from the Liberty Bell perceive Arch Street Meeting House. I try to put myself in their shoes to see the meetinghouse with new eyes. Is there adequate signage out front? Do people know what the word “meetinghouse” means? Is it clear that the meetinghouse is built on a burial ground? Do they think it is a sacred place? A great place to walk their dog? Just another old building? Are they looking for a spiritual experience or to hear about the Underground Railroad?

A new vision for Philadelphia’s oldest active meetinghouse

In 2015, Arch Street Meeting House Preservation Trust established the goal of making the meetinghouse the preeminent destination for the public to learn about Quaker contributions to society throughout history. In order to achieve this goal, the trust recognized that a new approach to interpreting the meetinghouse is essential. This sort of work doesn’t happen overnight; it is a daunting, multi-year undertaking, and the resources required to create a well-rounded interpretive plan for an historic site are sizeable. The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage offers a number of grants to art and cultural organizations, and there was one that specifically met the needs of Arch Street Meeting House—the Discovery grant. This funding made possible a yearlong project to take the first step toward developing a new approach to interpretation at Arch Street. By engaging Quakers in a dialogue with professionals experienced in creating interpretation strategies for historic sites both locally and nationally, we are learning more about the stories we can share with visitors and how best to share them.

Our vision is to have visitors of all ages from all over the world open the front door to the meetinghouse and become immersed in the life of the meetinghouse. By using stories from history, and language that visitors are comfortable with instead of Quaker jargon, we will be able to illustrate the ways in which Quakers live out their beliefs to an audience that knows little about Quakerism, past or present. Our vision for the future is to have engaging public programming based on a foundation of historical research that meets planned educational objectives. We seek to share tales of our rich historical past to illustrate living examples of Quaker principles in action without proselytizing.

According to our audience research data, the heritage tourists and school groups that visit Arch Street Meeting House understand it as an historic site first, then a sacred place. To me, these identities aren’t at odds with each other. For over 200 years, Arch Street Meeting House has served as a hub of Quaker activities. The benches were once occupied by Quakers who advocated for social justice and brought about monumental change, leading the movements for abolition, women’s rights, environmental concerns, and other causes that are still relevant today. Arch Street Meeting House is a platform we can use to shine a light on the role Quakers played, and continue to play, in shaping U.S. history and culture.

What I think would resonate with visitors both domestic and foreign would be an emphasis on social justice and liberation as a faith practice. Equality of genders, equality of ethnicities, equality of prisoners, the equality in dealing with Indigenous peoples, dignity of children, animals, nature. All sacred creation. We made mistakes and we are trying to learn from them. All visitors can identify with at least one of these aspects and all can rejoice that the traditional values and concerns remain embedded in what it means to be a Friend.

Hopefully this will bring some much needed attention to Quakers and we are, what we believe and the many wonderful things we have done and are doing.

My first experience with Quakers was at the Hampstead Heath Meeting House on the outskirts of London. What impressed me then and continues to resonant with me was a small sign above the gate at the front of the meetinghouse. The gate was always open and seemed to beckon folks to enter. The sign simply said, “All friends are welcome here”. But more important was that the Friends at Hamstead made an effort to welcome and extend friendship to all newcomers. As an American traveler, I was made to feel welcome and encouraged to return. Prior to and during the WWII, Jewish people who had fled from Germany were welcomed there. My belief is that the most important part of helping individuals connect with Friends is on a personal one to one basis and by extending a real welcome. In my opinion, only after a loving hand has been extended will people truly connect to the information about Quakerism and its history. Arch Street is a special place and I hope many will visit and find a welcoming place.