Review: Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement

Reviewed by Lincoln Alpern

May 27, 2014

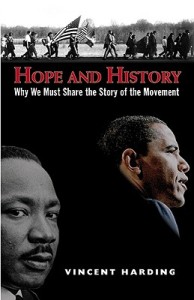

By Vincent Harding. Orbis Books, 2009. 223 pages. $16/paperback.

In Hope and History, Vincent Harding invites his readers to visualize themselves as educators—in the broadest possible sense—who must help their students of all ages learn the lessons of the Civil Rights Movement. With beautiful prose and a tone of gentle affirmation, Harding guides the reader through a collection of essays examining the movement, its impact, and ways to continue studying and sharing it.

Harding pointedly rejects the term “Civil Rights Movement” as too narrow. To him, it fosters the erroneous notion that the movement was solely about improving the situation of black people in the United States. This is a worthy goal, but one that isolates the movement and its effects from the broader landscape, relegating it to a specific time and place and a specific group of people.

The terms “black-led freedom movement” and “movement for expansion of democracy” are the ones Harding chooses, to emphasize that it was for everybody and stretched far beyond the specific issues we generally associate with the movement. For Harding, the struggle was at its core about expanded freedom, justice, and democracy for all. Every U.S. citizen is a beneficiary of the black-led freedom movement of the post-World War II era. We can and should affirm it as our past, and carry the spirit of the freedom movement into the future. It was, and is, about us; all of us.

The freedom movement inspired other movements for freedom and democracy at home and abroad, from women’s liberation to Tiananmen Square and revolutions in Eastern Europe, and Harding delights in pointing this out. For him, these examples demonstrate the universality of the human struggle for freedom and the relevance of each struggle for all the others. He reminds us that the effects of these movements stretch beyond their apparent physical, temporal, and issue-based borders.

One of the things that impressed me about Hope and History is the lengths to which Harding goes to be all-inclusive. He very carefully refers to “women and men” when speaking in general. After discussing the male-dominated images of the black artistic surge of the ’60s and ’70s, Harding points out: “At the heart of the magnificent ferment there was a powerful, vitalizing presence of black women poets, erupting everywhere on the landscape, sending down elaborately weighted plumb lines into the depths of our existence.”

The penultimate chapter consists of a series of epistles to various religious groups. One such is addressed to “you sisters and brothers who are members of churches where people of color (other than African-Americans) are represented in large proportion.” After naming Native Americans, “Hispanics/Chicanos/Latinos,” “a rich variety of Asians,” Pacific Islanders, and people “from the African diaspora in the Caribbean and Latin America,” Harding concludes: “I realize . . . that I am missing too many, but I trust that those missing on the list will know that you are present in my best intentions.”

If I were to name one (minor) drawback, I would say that Harding’s attention to detail can become a bit of a burden. His prose is engaging and his subject matter fascinating enough that most of his in-depth explorations are a joy and a pleasure. However, on the rare occasions when Harding hits upon a subject not to the reader’s interest, his comprehensive approach can be tiresome.

Each of Harding’s essays overflows with parental warmth and quiet optimism, while acknowledging that the struggle for freedom and democracy in the United States and the rest of the world is far from over. Harding is a big-hearted man with great faith in humanity. Hope and History is his own modest, thoughtful charge to his sisters and brothers of all races to carry on the movement.

This review appeared in the September 2011 Books column.

Hope and History was the #1 bestselling title at the 2013 Friends General Conference Gathering in Greeley, Colorado: Quaker Bestsellers (September 2013 issue)

Editor’s note: Dr. Vincent Harding passed away on May 19, 2014, in Philadelphia, Pa. Read more about his life by following the links below.

On the Acting in Faith blog from American Friends Service Committee: Realizing a dream: A conversation with Vincent Harding (interview transcript and audio; August 15, 2013)

From Pendle Hill Quaker Study Center: A letter from Vincent dated April 24, 2014 (describing how he approaches his “autobiographical journey”) written during his stay at Pendle Hill for a May 5 public talk, as part of the center’s First Monday Series of free lectures, films, and events

From On Being with Krista Tippett: Vincent Harding, In Memoriam–Civility, History and Hope (podcast; May 22, 2014)

From the New York Times: Vincent Harding, 82, Civil Rights Author and Associate of Dr. King, Dies (May 21, 2014)

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.