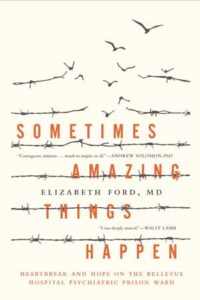

Sometimes Amazing Things Happen: Heartbreak and Hope on the Bellevue Hospital Psychiatric Prison Ward

Reviewed by Carl Blumenthal

June 1, 2018

By Elizabeth Ford. Regan Arts, 2017. 247 pages. $27.95/hardcover; $16.99/paperback; $14.99/eBook.

By Elizabeth Ford. Regan Arts, 2017. 247 pages. $27.95/hardcover; $16.99/paperback; $14.99/eBook.

How many of us could survive one day in New York City’s notorious Rikers Island jail, especially if we were mentally ill? Wouldn’t confinement in a psychiatric hospital be safer and more therapeutic?

As a peer counselor in the psychiatric ER of Kings County Hospital Center, one of Brooklyn’s public hospitals, I approach with caution so-called “emotionally disturbed individuals” charged with crimes. Even with one wrist handcuffed to a gurney, they are liable to react violently. The sooner they calm down and go to Rikers, the sooner our staff can focus on less agitated patients.

Having “done time” on psychiatric units as a patient and counselor, I expected a lot more heartbreak than hope in psychiatrist Elizabeth Ford’s Sometimes Amazing Things Happen. I was surprised to discover a role model who can multitask Friends testimonies.

Due to the revolving door between Bellevue and Rikers—the hospital has 68 beds to treat the most distressed of 5,000 inmates with mental illness—she admits, “I have come to see my success as a doctor not by how well I treat mental illness but by how well I respect and honor my patients’ humanity, no matter where they are or what they have done.”

Ford shines her Light not just on the jail’s insufferable conditions, but also on prisoners’ lives that are too often defined in diagnostic and legal terms. The list of their challenges—addiction, homelessness, poverty, illiteracy, racism, etc.—is long as an indictment. To paraphrase Black psychologist Amos Wilson, these men have learned to be the best at doing the worst.

In the tradition of Elizabeth Fry and Dorothea Dix—nineteenth-century prison and mental health reformers respectively, the first a Quaker, the second influenced by Friends—Ford proves one woman can make a difference by never giving up on her patients, even when society has cast them aside.

And they do their part merely by surviving. As one tells another in group therapy, “You are worth it, man. You got mad courage. You just hang on and keep going one day at a time. That’s all you got to do.”

Ford may never have taken a course in conflict resolution, but she’s a natural at calming potentially (self-)abusive patients and keeping the peace among staff—mental health providers and corrections officers alike. Even as she climbs the career ladder, there is always someone telling her what to do. Yet she’s not afraid to speak truth to power.

Her leading is to assume more and more responsibility for events others consider beyond their control, in the end becoming head psychiatrist of the city’s correctional health services.

Like a modern-day Noah, Ford is in her glory (or God’s) when evacuating the prisoners to an upstate hospital during Superstorm Sandy and finding refuge elsewhere for those re-housed on Rikers Island, where she discovers just how poorly the mentally ill are treated.

Is Ford too good to be true? Except for a few moments of self-congratulation, burnout seems to be her only shortcoming, but that’s because she cares too much. Her family and therapist keep her on an even keel; she recognizes her social and economic privileges. And there are events out of her control, such as the beatings, murders, suicides, and escapes she learns about secondhand.

Ford’s memoir has the pacing of a well-directed movie, with enough drama to satisfy the most jaded fans of “loony bin” tales. Her prose is straightforward. Her eye for detail demonstrates the mindfulness necessary to survive amidst daily trials and tribulations. She enables us to witness what others can’t or refuse to see.

Thus, it’s the small blessings that give her and us hope: a phone call home by a scared teenager, a disheveled prisoner’s unexpected shower, proper clothes for court arraignments, a sing-along in community meeting, ping-pong on a makeshift table, and a patient forgiving a doctor’s mistake.

Her coda for Sometimes Amazing Things Happen: “a story without an ending is still a story worth telling.” Meaning these are snapshots of lives that we must honor, no matter how difficult to appreciate.

Despite Friends history of psychiatric and prison reform, our support for originally benevolent “asylums” and “penitent-iaries” has unfortunately been turned against those we tried to save. However, if we follow Elizabeth Ford’s lead, redemption is still possible. (For instance, we can join American Friends Service Committee’s Prison Watch to shed light on the solitary confinement that causes and worsens mental illness.)

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.