What Our Quaker Ancestors Can Teach Us about Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Pennsylvania Hall officially opened its doors on May 14, 1838, and welcomed all Philadelphians to the celebration, regardless of race, sex, or status, a co-mingling and inclusivity never before witnessed in Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love. Built by abolitionists as a “temple to free discussion,” it stood just four days before a mob, enraged by the politics of “race-mixing” and women and men speaking together equally, destroyed it by fire. Inclusion and equity have always been incendiary. Like the unrelenting assault to crush diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) ravaging our nation today, the burning of Pennsylvania Hall is a similarly tragic illustration of just how deeply our fear of cultural diversity runs and how easily that fear ignites into violence.

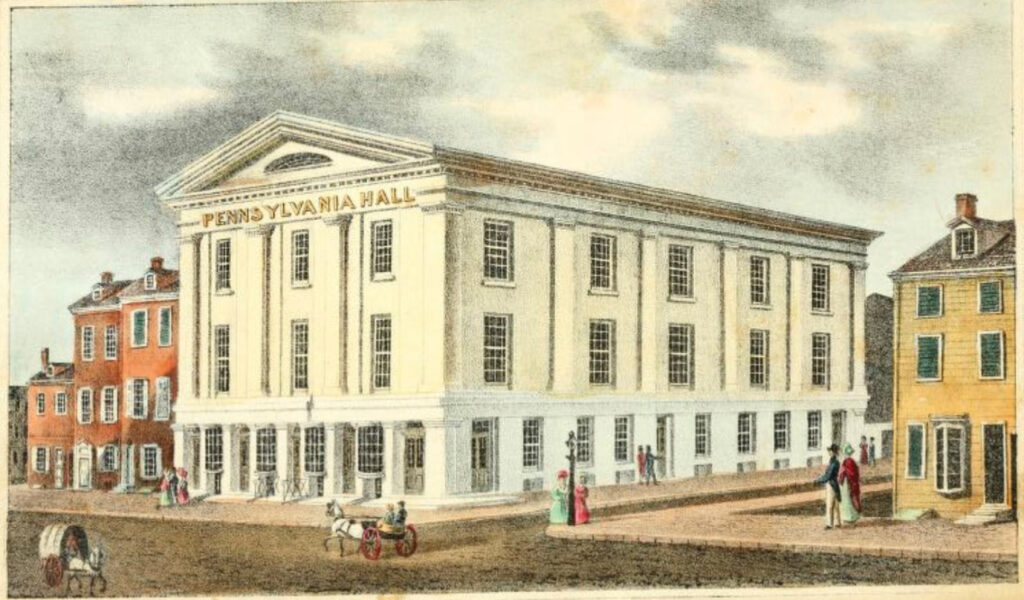

Pennsylvania Hall was an impressive three-story structure built by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, which sold $20 shares to two thousand individuals to fund its construction. Countless others contributed labor and materials. Often the target of violence, abolitionists were unable to obtain venues willing to risk hosting their meetings. Pennsylvania Hall was their solution, a safe environment where abolitionists, women’s rights advocates, and other reformers could assemble and speak freely.

The hall housed an abolitionist bookstore, reading room, newspaper, and store stocked with slave-free labor products. Still, naming it Abolitionist Hall would mark the building as a target; a safer choice was made: naming it after the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

It was situated in the center of Philadelphia in a Quaker neighborhood, generally more supportive of the abolitionists’ cause and home to many Quaker reformers, most notably Lucretia Mott. Mott, a key figure in the Convention antislavery meetings taking place during that opening week, herself became a target of the mob’s rage on the night they destroyed Pennsylvania Hall.

The hall stood just blocks from the old Pennsylvania State House, where the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution were signed (abolitionists were just starting to call the statehouse bell the “Liberty Bell.”) The location of Pennsylvania Hall was a metaphor for the abolitionist movement: these reformers believed that they were advancing the fundamental principles of democracy. Yet, those foundational symbols also cast a very dark shadow insofar as they also codified the right to own slaves and bestowed the rights of liberty and citizenship on White men only. Forty-one of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence owned slaves.

In Pennsylvania Hall, these radical beliefs about democracy and equality were not only discussed but practiced, providing an actual glimpse into their possible realization, a realization that remains deeply threatening and under attack today.

During the four days that it stood, various antislavery meetings were held in Pennsylvania Hall, and those events were attended by Blacks and Whites, men and women, who mingled and spoke as equals. These brazen politics of inclusion and equality stood in stark contrast to the realities of the day, when more than two million people remained enslaved. Amalgamation or race-mixing was taboo, and women were still without any individual rights and, if married, were the legal property of their husbands. The conflict was increased further by women speaking in public, a violation not only of religious and cultural norms for womanhood but also labeled promiscuous when the audience included men.

Anger about the “co-mingling” of races and sexes attracted the attention of pro-slavery Philadelphians and others who perceived these reformers as enemies of the family, religious teachings, and the commonwealth. Angry citizens began gathering outside of Pennsylvania Hall from the time it opened, and the crowd grew larger every day.

In response to the increasing hostility and anger towards these inclusive gatherings, the building managers requested protection, but the mayor, believing they were responsible for inciting such anger, asked them to end their proceedings. In the event they decided to continue, he asked that the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, the premiere event scheduled that week, restrict its gathering to White women only.

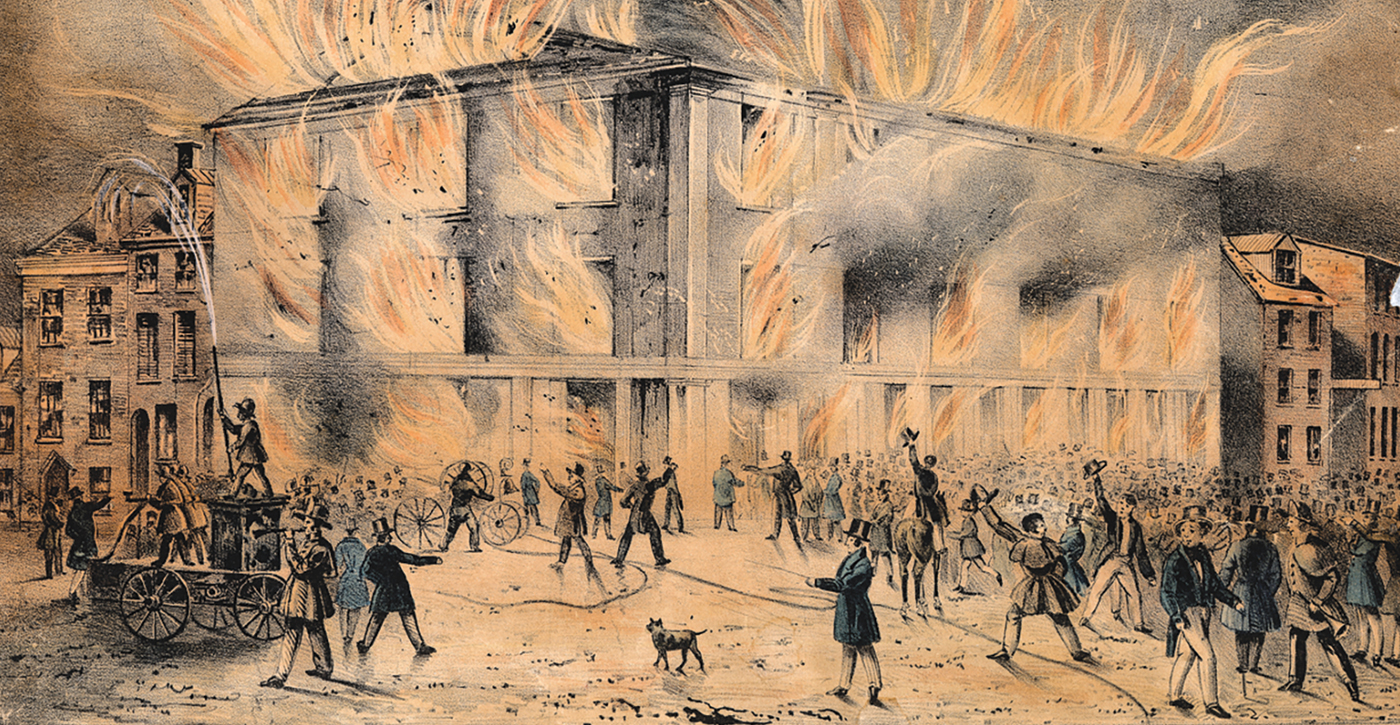

The evening before Pennsylvania Hall was destroyed by arson, 3,000 abolitionists had gathered to hear several well-known antislavery speakers. A mob smashed through windows and broke into the Hall. The reformers remained for another hour while a number of notable abolitionists addressed the audience.

Wednesday night, notices were posted throughout Philadelphia that called on citizens to protect the Constitution and stop the indecent behavior, by force if necessary, that was taking place in Pennsylvania Hall. Lucretia Mott conveyed the mayor’s message to the antislavery women on Thursday afternoon. The women refused the request and then left the Hall united, arms linked—Black and White together—protecting each other from their attackers, although, of course, the Black women were at infinitely greater risk. The mob outside grew larger and more belligerent.

By the evening of May 17, the mob had grown to around 17,000 White men. The mayor arrived demanding the keys to the building, telling the crowd to disperse. He then left. Soon after, the mob stormed the building and set it ablaze. Firefighters arrived but were instructed to let it burn; no one was arrested.

Their next target was the home of Lucretia Mott. Refusing to flee and be taken to safety, she waited for the mob with her husband, James, and Quaker schoolteacher and abolitionist Sarah Pugh. Sarah later commented that she had never seen such composure in the face of danger, something Lucretia attributed not to herself but to that of God within. It was only because an abolitionist ally had infiltrated the mob and deliberately misled them away from the Mott’s house that they escaped its violence. The mob then went on to burn the Shelter for Colored Orphans, being constructed just several blocks from Pennsylvania Hall, and damage Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, which belonged to a Black congregation.

Southern papers gave high praise to the pro-slavery mob for interrupting the radical and immoral agenda of abolitionists, and at least one Northern paper also blamed the abolitionists for bringing the violence upon themselves by their promiscuous, race-mixing actions, a conclusion with which the official report conducted by the city of Philadelphia agreed.

The burning of Pennsylvania Hall happened within the context of a nation increasingly polarized over slavery. The Abolition Movement gained momentum in the 1830s in conjunction with the increase of abolitionists’ publications, reformers, and freed slaves. As the horrors of slavery were exposed, the moral indignation and political opposition to it gained strength, primarily among Northerners. The national tension over slavery, always simmering beneath the surface, was beginning to erupt.

Just six months before the burning of Pennsylvania Hall, a pro-slavery mob in Illinois murdered Presbyterian minister, abolitionist reformer, and newspaper publisher Elijah P. Lovejoy. His murder shocked much of the nation. John Quincy Adams described it “as of an earthquake throughout this country.” It was an outrage undoubtedly sparked by not only the brutal ignorance behind his death but also the fact that Lovejoy was White. Like Lovejoy’s murder, the burning of Pennsylvania Hall mobilized reformers and accelerated the Abolition Movement, leading to a more deeply divided and polarized nation.

In Pennsylvania Hall, these radical beliefs about democracy and equality were not only discussed but practiced, providing an actual glimpse into their possible realization, a realization that remains deeply threatening and under attack today.

Intended to crush free expression and terrorize reformers, the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall instead cast a spotlight on the savagery of pro-slavery politics and the threat it posed to the rule of law and democracy. Historians mark it as a pivotal moment in awakening Northerners to the urgency of ending slavery.

Just as U.S. President Donald Trump said “nothing” was done wrong on January 6 after a Republican voter confronted him and then described the attack as “a day of love,” some eyewitnesses to the burning of Pennsylvania Hall saw the mob another way. One journalist who was “on the spot when the fire began” and was there throughout wrote: “You may call it a mob if you please; but I never saw a more orderly, and more generally well informed class of people brought together on any other occasion where the meeting was called a mob. There was no fighting, no violence to private persons, or property.” This is another stunning example of how our beliefs shape what we see and how our versions of history reflect the values and beliefs of those who tell it.

The charred skeleton of Pennsylvania Hall was left untouched by the City of Philadelphia for two years. Although a grim reminder of the danger of using our freedom to speak on behalf of equality, it nonetheless quickly became a monument to the Abolition Movement and a pilgrimage site for reformers.

On the morning following the fire, the American Convention of Antislavery Women met in a local schoolhouse to conclude its work. Some abolitionists had asked them to remove any mention of Black and White women meeting together from their minutes and to reconsider this practice. In response, Lucretia Mott called on the Convention to strengthen their commitment to racial equality, and they passed a resolution that all antislavery work must include Blacks and Whites working together as equals.

Other abolitionists saw the fire as a backlash to mixing the cause of slavery with women’s rights, claiming they were two distinct movements and needed to be kept separate, something Lucretia Mott considered senseless, asking why would anyone expect women to work to free slaves but not themselves?

The progressive politics of equality and inclusion were central to the platform of the American Anti-Slavery Society founded in 1833 by the prominent abolitionist and newspaper publisher William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison advocated an immediate end to slavery, complete racial integration, and full rights of citizenship regardless of race or sex. In Pennsylvania Hall, these radical beliefs about democracy and equality were not only discussed but practiced, providing an actual glimpse into their possible realization, a realization that remains deeply threatening and under attack today.

The current assault on DEI is widespread and unrelenting. Those who continue to defend it are being threatened by the full power of the state. Some historians liken the current effort to crush inclusion and equality to the period following Reconstruction. Adam Sewer has called it the great resegregation.

DEI programs and initiatives spread quickly across the United States, largely in response to the death of George Floyd in May 2020 and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. They were intended to promote the inclusion and success of historically marginalized and excluded groups. Although DEI covers multiple identities, it is often solely associated with race and sex.

DEI also quickly became the rhetorical scapegoat for the nation’s problems, vilified as corrupting the practice of reward for individual merit and the principles of equality and democracy. It’s claimed that it was DEI that was actually promoting discrimination, especially against White men. The phrase “DEI hire” became a sort of devil term, something unworthy that ought to be avoided and eliminated. It soon became the cause of every tragedy including air crashes, wildfires, and inflation.

In his March 4, 2025, address to Congress, President Trump declared that he had “ended the tyranny of so-called diversity, equity, and inclusion policies all across the entire federal government and, indeed, the private sector and our military. And our country will be woke no more.”

Like the current effort to crush and purge DEI, the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall was a shocking and traumatic event for advocates of equality. Their response is instructive. While some reformers were intimidated and silenced, others who had been in the cross hairs of the mob’s violence—like Lucretia and James Mott—were strengthened in their resolve. They saw the world differently, having come face-to-face with the horrific ignorance and violence behind our fear of inclusion. James Mott later described his experience as being cathartic in a letter to Anne Weston: “The color prejudice lurking within me was entirely destroyed by the night of Pennsylvania Hall.”

Almost two hundred years later, within a still deeply divided and polarized nation, this same fear of diversity, equality, and inclusion is dismantling decades of struggle for equal rights. With the exception of some corporate and institutional leaders (like Harvard University) and legal challenges, there has been a muted resistance. Yet, we stand in the shadow of Pennsylvania Hall. Those reformers who responded so bravely in the face of mob violence are reaching out to us today.

I think the reformers who spoke at Pennsylvania Hall were trying to reform the views of society that were inconsistent with the concepts of American liberty so that American liberty could extend to every person on American soil regardless of race and gender. Those who share the principles of DEI (Diversity, Equality, Inclusion); if I am not mistaken (please correct me if I am wrong), are however trying to address what they perceive as problems with American liberty so that America can be more inclusive of other cultures who may not share those fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed to American citizens.

It further seems to me that the reformers who spoke at Pennsylvania Hall embraced those fundamental rights and freedoms that are now under attack in the name of diversity, equality, and inclusion. According to what I have read here, reformers like Lucretia and James Mott were not trying to incorporate a new set of principles to perfect, and or take the place of the fundamental principles of American Liberty. They just wanted American liberty to extend equally to all persons regardless of race and gender.

Personally, I think people abuse their American liberties and lord it over others. And mislead others. But I also think that you can’t force people to surrender to God’s will by trying to place limits on liberty. That kind of reform only leads to higher more powerful forms of corruption. But we can demonstrate a better way by our actions, and I think Quakers do that very well.