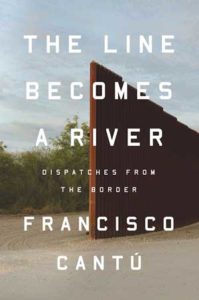

The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border

Reviewed by David Austin

January 1, 2019

By Francisco Cantú. Riverhead Books, 2018. 256 pages. $26/hardcover; $17/paperback (available February 2019); $12.99/eBook.

By Francisco Cantú. Riverhead Books, 2018. 256 pages. $26/hardcover; $17/paperback (available February 2019); $12.99/eBook.

Buy from QuakerBooks

Almost four years ago, I reviewed a book for Friends Journal entitled Bishops on the Border, which told the stories of faith leaders who are engaged in activism on behalf of immigrants attempting to cross the southern borders of the United States. Reading that book helped galvanize my feelings about that issue. And as it happens, while I was reading The Line Becomes a River, the country was riveted by news coverage of the crisis being caused by the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance policy,” which resulted in thousands of children being separated from their parents as they crossed the southern border. As I write, that deplorable situation has still not been completely rectified. Watching that slow-motion atrocity unfold made me feel helpless, angry, and frustrated. About the last thing I wanted to do was read a book that might somehow humanize the people who were carrying out these atrocious policies, which is what I assumed this book was all about. So I really expected to hate this book.

And then I sat down and read Francisco Cantú’s story.

Cantú spent his childhood near the border, raised by the granddaughter of an immigrant, herself a former federal employee with the National Park Service. Freshly minted college degree in hand, Cantú joined the U.S. Border Patrol, determined to experience what was happening on the border firsthand. It was a decision that worried his mother and puzzled his colleagues, who didn’t understand why someone with a college education would want such a job. Cantú himself was sometimes perplexed about his choice, and this inner conflict was frequently reflected in his dreams, which Cantú explicitly recounts throughout the early chapters of the book. He also graphically recounts the misery, desperation, tragedy, and death that he encounters on an almost daily basis, along with the sometimes vile and violent responses of his colleagues in law enforcement. Be warned that this is not a story for the faint-hearted: the instances of cruelty and suffering recounted here are disturbing and sickening.

While documenting his life as a Border Patrol officer, Cantú intersperses discussions about the history of the border between Mexico and the United States, along with considerations of topics such as the destructive psychological effects of long-term exposure to the kinds of violence he and his co-workers experienced (and perpetrated) as part of their work. It is the strain of such experiences that eventually forces Cantú to leave the Border Patrol, but even then, he is not free of that life. While working in a service job, Cantú is pulled back into the turmoil and terror on the border when an immigrant friend, José, is detained after attempting to visit his dying mother in Mexico, an experience that to me was eerily reminiscent of some of the more recent stories about forced family separation.

It’s worth noting that when this book was released and Cantú went on the obligatory book tour, his appearances were met with protests. The demonstrators no doubt saw him as just another Border Patrol agent, a brown-shirted symbol of a system that brutalizes and dehumanizes its victims. To them, he was just another thug with a badge. With all due respect to those protesters—and I can easily envision myself as having joined them if I hadn’t bothered to read this book—Cantú, to me, is a casualty of this system.

Near the end of the book, as he’s trying to make sense of what he’s done, what he’s seen, and what he’s dreamed, Cantú recalls a conversation with his mother where’s he trying to make sense of everything he’s been through, of all the violence he’s been part of and that he’s observed. She responds this way:

What I’m saying is that we learn violence by watching others, by seeing it enshrined in institutions. Then, even without choosing it, it becomes normal to us, it even becomes part of who we are. . . . The part of you that is capable of violence, maybe you wish to be rid of it, to wash yourself of it, but it’s not that easy. . . . You can’t exist within a system without being implicated, without absorbing its poison.

If this brilliantly written book teaches us nothing else, it’s worth paying attention to that lesson. We are seeing things now on a daily basis that are symptoms of a system that lacks even the most basic elements of human decency, compassion, and empathy. It is truly inhumane and inhuman. The manifestations of that system permeate so many aspects of our daily lives that we risk becoming desensitized and immune to it all. We do so at the risk of losing whatever is left of our humanity and our very souls. Francisco Cantú chose to go through his own personal hell to understand that. The least we can do is listen.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.