Corvallis Meeting in Oregon is a small but vibrant unprogrammed meeting, with a Sunday attendance of 20 to 25 worshipers. I first showed up at the end of October 2004, with only a slight acquaintance with Quakerism. I was seeking peace and quiet after moving with my husband across the country from Massachusetts; I was also seeking a spiritual home. Would this be a good place for me?

The meetinghouse had originally been a residence. As I came in the door, I glimpsed a long, narrow living room on the right with a lot of closed doors. The hexagonal worship room on the left had chairs arranged in two concentric circles, windows on four sides, and six big beams that supported a skylight at the top. This lovely space was totally unlike any of the dozen East Coast meetinghouses that I had visited for weddings.

I relaxed into the silence. I came back regularly.

Over the next few years, I grew to love silent worship. Some people befriended me. I started going to meeting for business. I learned some Quaker jargon and practice. I increasingly appreciated Quaker process and testimonies. This was a good place for me.

Lovell proudly showed me the clipboard where Friends signed books out and in again (it didn’t seem to have been used much).

In 2006, the nominating committee asked whether I would like to serve as assistant librarian. I hadn’t even been aware that there was a library since it was behind a closed door at the far end of the original living room, but nonetheless I agreed to help Lovell, the elderly, long-term librarian.

When I came to meet Lovell in the library, I stepped into a small room reeking of mildew. The library was about ten by fifteen feet, with three walls of shelves crammed with books and papers. Lovell’s desk was on the fourth wall. There were two windows with venetian blinds, a noisy heater, and a flickering fluorescent ceiling light.

Lovell proudly showed me the clipboard where Friends signed books out and in again (it didn’t seem to have been used much). She pointed out the labels on the shelves: Pendle Hill pamphlets, Bibles, children’s books, religious education, biography, autobiography, psychology, Quaker history, Quaker fiction, Christianity, general religion, and quite a few more.

Lovell’s current project was checking that all the books on the shelves were stamped “Corvallis Friends Meeting” on the flyleaf and had author and title cards in the metal file boxes on her desk. At her direction, I sat on the floor in front of the children’s books and checked whether they had been rubber-stamped. If not, I passed them up to her.

One shelf held classic picture books like The Little Engine That Could and Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham. Below it was a shelf of books for upper-grade readers, most of which had inscriptions on the flyleaf like “For Millie on her ninth birthday.” Millie had evidently loved these books—the covers were coming loose, and the gold-leaf titles on the spines were worn away. They seemed to be stories about heroic Quaker girls of the eighteenth century; I couldn’t imagine any contemporary nine-year-old I knew being interested in them. Almost all the rest of the books had bookplates inside saying, “Gift of Paul and Crystalle Davis.” The Davises’ donations mostly dated to the 1940s. They didn’t show much sign of wear, but when I opened them the smell of mildew was overwhelming.

I went home wondering what I had gotten myself into. I wondered about the purpose of the library—if it had one beyond storing the children’s and adult books of the two deceased women, Mildred Burke (presumably young Millie) and Crystalle Davis. I asked some longtime members whether they had any thoughts on the subject. They spoke fondly of Mildred and Crystalle, but had no ideas about why we had a library.

I took the liberty of discarding them. When I reported this move at our next meeting for business, Friends almost cheered.

When Lovell retired from the library, the nominating committee asked me to take over her position. I was delighted at the prospect of having free rein to bring the library closer to what I thought it should be. However, I said I didn’t want to do it alone.

I started assessing the collection, beginning with the psychology section. This seemed to me an unusual subject for a Quaker library, but what did I know? I found that “psychology” consisted mostly of self-help books from the 1960s with crumbling, yellowed pages and advice about looking your best when your husband comes home from work. I took the liberty of discarding them. When I reported this move at our next meeting for business, Friends almost cheered. My confidence increased.

Next I tackled children’s religious education materials. I found a whole collection of non-Quaker magazines still wrapped in plastic. One had an article about how to help children confess their sins. Confessing individually would be too hard for them, so they should sit in a circle and take turns. As a former kindergarten and elementary school teacher, I had a good idea of how that would go.

“I hided my daddy’s shoes.”

“I hided my mommy’s shoes.”

“I hided my mommy’s and my daddy’s shoes.”

“I hided everything in my whole house!”

Why had anyone ever subscribed to this magazine?

There were six or eight boxes of children’s religious education materials of dubious use, but I was reluctant to throw them all out so I invited Friends to a Saturday morning discard party. The meeting clerk and her partner showed up and merrily threw almost everything on the floor. I would not have been so daring myself, but I respected the decisions of these two seasoned Friends.

Marilou became the second librarian. One morning she brought a screwdriver from home and I brought some sheer curtains, and we surreptitiously replaced the venetian blinds with the nearly transparent curtains. The room was now just a bit more pleasant to work in. We always kept the door open, of course.

In March 2010, I wrote a report on the state of the library, which I presented at meeting for business. The library held roughly 1,000 books (many of them out-of-date), some framed pictures, random stacks of journals, pamphlets and manila envelopes, and a lot of other stuff I thought was junk. Furthermore, books were reshelved at the librarians’ whim. The report ended with questions.

Marilou and I interviewed all the committee clerks and anyone who had signed a book out in the last 18 months by phone. Responses were sometimes similar and sometimes in direct conflict, but we squeezed out some recommended actions. Among them were to write a statement of purpose; to discard books, but leave them out for Friends to take home or return to the library; to get a budget and buy new books; and to write blurbs in the newsletter about new acquisitions.

Marilou and I had already started implementing some of the suggestions. We set about discarding books. Is it smelly? It’s out! Falling apart? Outdated? A duplicate? Throw it out! We had a good time with this purge. We packed the discards into cardboard boxes, and Marilou taught me to kick the boxes across the floor rather than try to carry them. We invited meeting participants to return to us any books they thought the library should keep and take home any they wanted. Interestingly, only in the peace section were books frequently returned.

I wrote a statement of purpose. It started: “The purpose of the library is to enrich the life of the meeting by giving members and attenders, including newcomers, access to Quaker and Quaker-related books and materials. We focus on books that are not easily available elsewhere.” It described the subjects we thought should be included and wound up: “We want the library to be a welcoming space with materials attractively arranged. We want to be mindful of avoiding information overload and of the Quaker value of simplicity.”

Meeting for business accepted it without a quibble—a good boost to my Quaker confidence.

Pat had worked in the library with Lovell before I did, had resigned, and was now interested in coming back. This made us a committee of three, which turned out to be a good number. Pat hated to see books discarded, so she took on the task of finding new homes for them at nearby monthly meetings, George Fox University, or the public library’s book sale.

We developed criteria for choosing new books from the reviews in Western Friend and Friends Journal. Is it written by a Quaker? Is it about Quakerism? Is it about a subject of interest to our meeting? Does it fill a gap in our collection? Is it likely to be available at the public library? We bought them from QuakerBooks of Friends General Conference.

I thought we were moving in a good direction. Other Friends told me they agreed. There didn’t seem to be anything we could do, however, about the unwelcoming, unattractive little room.

Then, with perfect timing from my point of view, the meeting started planning a remodeling project that would incorporate the library into a large open space composed of the kitchen, the children’s program room, and the living room. Some decisions were contentious, but once we reached unity, Charles and Bob (our volunteer coordinators for major meetinghouse maintenance) hired a contractor.

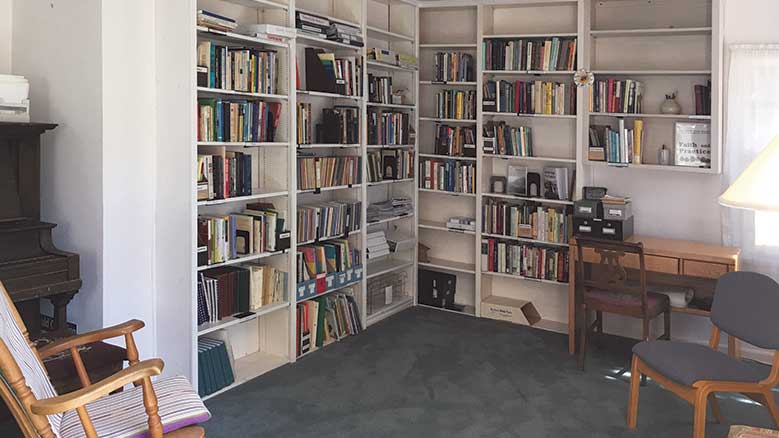

The contractor and his team hung lots of plastic sheeting and knocked out walls; they installed baseboard heating and new ceiling lights; they laid new carpeting. Once the plaster dust had cleared, the space was large and airy with natural light from windows on the two long sides. Bob and Charles built new adjustable-height shelves for the library along the back wall and one of the side walls. The library space had been transformed, and was ready for further transformation by the library committee.

The handwritten notes in the envelope had clearly been important 20 years ago, but it seemed unlikely that anyone would ever want them again. We took them home for our recycling bins.

We unpacked the books and decided where to put them. For the sake of simplicity, I suggested that we combine biography and autobiography, making it easy to find books about, say, William Penn. We separated out books on peace, and had two half-shelves for justice and the environment. I added a half-shelf for simplicity. We created a shelf of books for newcomers.

We combined two small sections—meditation and prayer—into a single half-shelf section, and we returned the children’s books to the children’s program. We set aside a space to save two years’ worth of Western Friend and Friends Journal issues—but no more. We looked briefly at the piles of papers and the manila envelopes with, for example, “Apartheid talks, 1985” scrawled on their fronts. The handwritten notes in the envelope had clearly been important 20 years ago, but it seemed unlikely that anyone would ever want them again. We took them home for our recycling bins.

I took on the “general religion” section myself. I changed its name to “world religions.” I felt it was useful, even important, to fill out this shelf, since the meeting had participants from many different religious backgrounds, participants who’d volunteered and lived in countries with a range of religions, and participants with limited perspectives outside of Christianity. It took a lot of research on the Internet, at the public library, and at Corvallis’s sole Jewish congregation (where the Rabbi was very helpful) to choose books on world religions, but the process was interesting and educational for me.

I bought so many books on Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and all the rest from our wonderful downtown independent bookstore that they gave me for free a big coffee table book on world religions, full of lovely photographs.

In 2013, I reported to meeting for business that the library was attractive, well-organized, and easy to use. We’re still working on it, of course: adding new books, orienting newcomers to the clipboard sign-out system, and dealing with miscellaneous debris that people sometimes park on empty sections of the shelves. There’s no question, however, that the library has been transformed. It’s out of hiding, up-to-date, and contributes to the life of the meeting.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.