Can the spiritual disciplines of early Friends help us through hard times in the 21st century? The very question of spiritual discipline is complex for contemporary Friends. For the most part, we do not hold up an expectation that Friends should have any spiritual practice except for attendance at meeting for worship. One rarely hears the term “spiritual discipline.” Some of us bristle at the term “discipline,” thinking of it as something administered by a teacher or parent rather than simply as a practice that develops proficiency. And among Friends “spiritual” can have a wide, and sometimes troubling, range of meanings.

We don’t talk with one another about spiritual discipline because of our general hesitation about telling one another what spirituality is and how to develop it. As a consequence we are often left to find our way alone, without support, guidance, or milestones. Many of us get stuck or lost, or find ourselves going around in spiritual circles.

Here in the early 21st century we are living in hard times that look as though they are going to get harder. Our country was attacked; we have been told to expect long-term war; the natural environment is compromised; the economy is unstable; jobs are at risk; retirement savings are shrinking; many people live without the basic necessities. If we are to face the crises of the early 21st century we can’t be going around in circles—we are going to have to help one another find a robust spirituality.

Our Quaker testimonies are demanding. What do Integrity, Equality, Simplicity, and Peace require of us? How can we build the spiritual strength and stamina to live up to these testimonies when we are challenged?

We know how physical strength and stamina are developed: exercise, practice, repetition, discipline. The same is true of spiritual strength. Many Friends, sensing this need to build up spiritual strength, seek disciplines outside Quaker practice. We may take up Buddhist meditation, or yoga, or chanting, believing Quakerism not to have equivalent practice that will hold us and carry us through hard times. However, I am discovering that our tradition does offer us calisthenics that can help us develop the strength and stamina we need to be a healing presence in a troubled world.

It may be that when we first encounter the spiritual disciplines of early Friends, we will have to get inside their language and translate it into terms that have meaning for us today. Some of early Quaker language is unfamiliar to us. Sometimes the words are familiar, but the meanings are different. Nonetheless, my sense is that the disciplines of early Friends are accessible to contemporary Friends. Not only can we understand them, I think we will find that they do not cramp Friends into narrow, sectarian beliefs; instead, they can strengthen each of us on our personal spiritual path.

This brief article lifts up five early Quaker spiritual disciplines for our times: retirement, prayer, living in the Cross, keeping low, and discernment. This is not an exhaustive list of the practices of earlier Friends, but a suggestive group that can be a starting place for building strong spiritual lives in supportive spiritual communities.

Retirement

Retirement may be the practice most accessible to contemporary Friends. Our meetings for worship are times of retirement. Walks in the woods or sitting by the ocean can be times of retirement, as can retreats extended over several days. Thomas Kelly wrote that we can be in contact with “an amazing sanctuary of the soul, a holy place, a divine center.” Times of retirement are the times when we pull back from the chatter and busyness of our outward lives, enter that amazing sanctuary, and allow our inner wisdom, the Inward Teacher, to rise up in us.

For early Friends retirement was a prerequisite for a life of faithfulness. Retirement was a daily discipline, sometimes many times in a day. We may think that at the pace of 21st-century life, there isn’t time for daily retirement, yet retirement is a basic building block for all other spiritual disciplines. We have to pause, let the static quiet, so that we can hear. Thomas Kelly reassures us that if we establish mental habits of inward orientation, the processes of inward prayer do not grow more complex, but more simple.

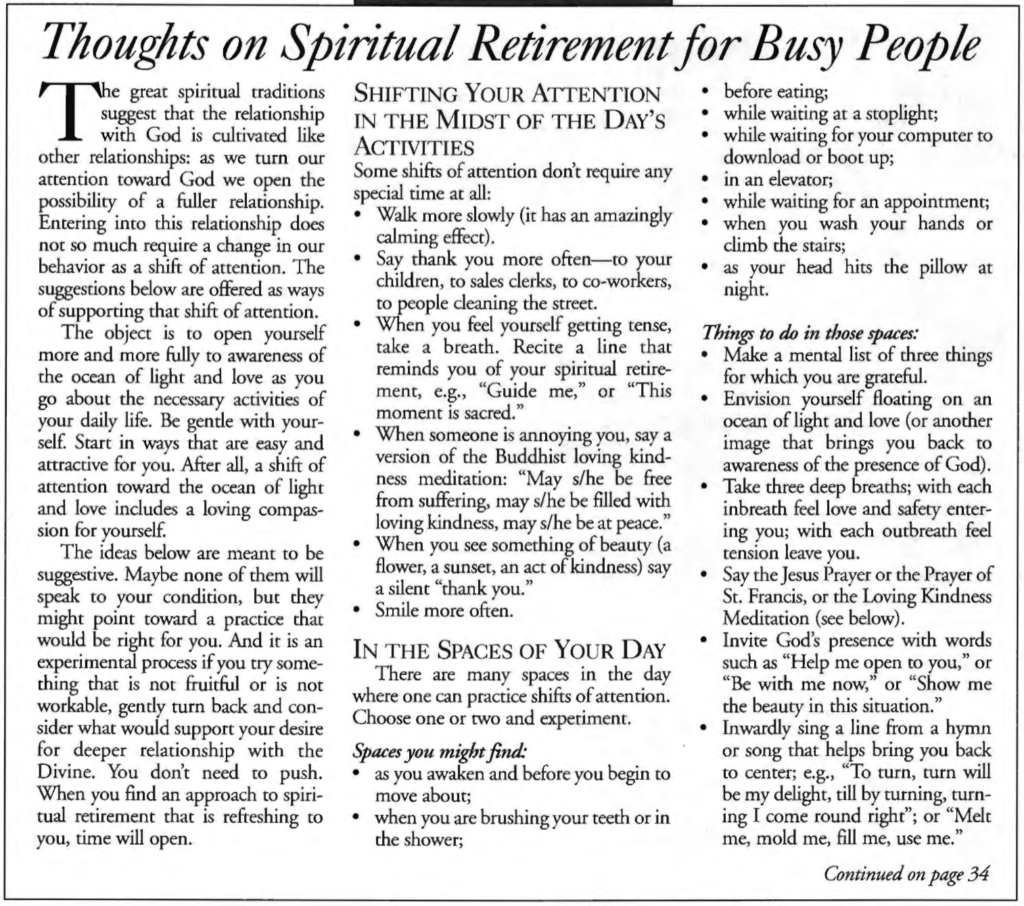

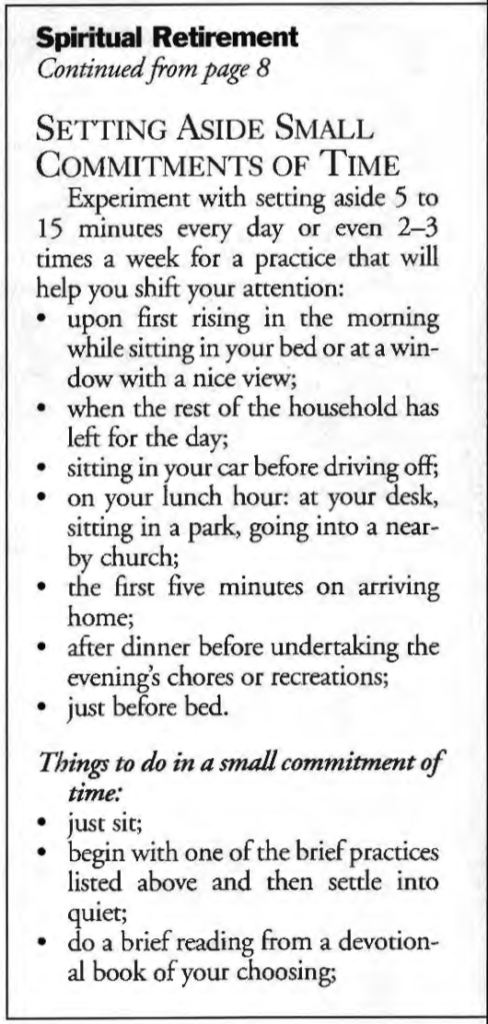

A couple of years ago I developed a two-page guide for members of my meeting on personal spiritual practices, “Thoughts on Spiritual Retirement for Busy People” (see sidebar). It suggests beginning with times of retirement that take no time out of your day. Sitting in traffic, waiting for an appointment, or waiting for your computer to boot up are wonderful times for briefly turning inward. From those small moments one can develop a habit of retirement that may effortlessly grow into more extended periods.

Prayer

Prayer is a tough word for a lot of Friends; if you need to do so, translate it into a more comfortable word as you read along. Many contemporary Friends want no part of a practice in which one dials up God to make demands. Some Friends don’t believe in a personal God who is there to hear and respond. Others think that making demands is a poor way to enter into relationship with a personal God. They would get support from Teresa of Avila who wrote, “If we want the Lord to do our will and lead us just as our fancy dictates, how can this building possibly have a firm foundation?”

Prayer at its fullest is something more than importuning God. I have discovered that many Friends have practices that I regard as prayer in this fuller sense, though they may not consider them to be prayer.

For me, prayer is entering into relationship with the Other. If retirement is a time of going inward and contacting the Inward Teacher, prayer is entering into relationship with that which is beyond and outside. Even if we do not experience a personal God, many Friends find themselves in awe of the larger whole and of our interconnections with one another and the mystery of the universe. Prayer can be as simple as acknowledging that awe when we see a sunset or a newborn baby or a flower growing in an unlikely place.

Prayer can take the form of gratitude. Meister Eckhart is said to have written, “If the only prayer you say in your life is ‘thanks’ it would suffice.” Dag Hammarskjold expressed this in his Markings: “For all that has been, thanks; for all that will be, yes.”

Prayer may be lived out in our longings. Patricia McKernon, who has shared her music at Friends General Conference Gatherings, writes in one of her songs, “Your longing is your surest love of me.” Bill Taber, a teacher from Ohio Yearly Meeting, says that yearning (what we today might call longing for wholeness) was the underpinning of early Quaker seeking.

Contemporary Friends talk of “holding in the Light.” By this we may mean holding someone in loving thoughts while they go through a hard time—or perhaps we mean holding a vexing matter quietly in the back of our consciousness and allowing new possibilities to emerge. And we speak of seeking guidance or being open to guidance, perhaps from the Inward Teacher, perhaps from the wisdom of the universe.

Prayer expresses our hope and intention to enter into an awe-filled relationship with the Divine. An individual who becomes practiced in prayer can have the experience of sinking down into the Divine in which no words are needed.

Just the sincere act of trying to enter into a relationship with God can be transformative for the person praying. Through a discipline of prayer one can create within oneself an environment that is more receptive to God, more sensitive and more open to God’s presence in the world, and more receptive to and aware of guidance.

Whether or not we call it prayer, it is important to our spiritual discipline to recognize our place in the wider scheme of things. We are not the center. We can recognize that there is wisdom without as well as within, and we can salute the sacredness of other people and of the entire universe. Acknowledging this place provides a foundation for the disciplines that follow.

Living in the Cross

This term will sound entirely foreign to many contemporary unprogrammed Friends, and too Christocentric for some, yet the practice it represents is often found among us, even among those whose spirituality is not based in the Christian concept of the Cross.

“Living in the Cross” is to put our own will aside, and to submit to the guidance discovered through retirement and prayer. It means not to turn away from the suffering world, but to face even the suffering that we are powerless to alleviate. It means to allow the Light to shine into our dark spots and show us the way—and to follow that way even when we are tempted to take an easier path.

John Woolman continually looked to his way of living to discover the seeds of war and injustice. Living in the Cross requires that we discover the equivalent for us today of releasing our slaves or of giving up dyed clothing. Living in the Cross requires that we uproot those seeds from our lives and step outside the oppression and injustice of the dominant culture. In a recent retreat on “Being Quakers in Difficult Times,” Laura Magnani of Pacific Yearly Meeting taught, “If we have experienced a God-centered reality we can’t continue to participate in the empire-centered, First-World culture.”

This discipline is spiritual heavy lifting. It is not a discipline that leads to a cozy, comfortable spirituality, but to a strong, robust spirituality that faces suffering with courage and strength.

Keeping Low

Here is another term that is foreign to our vocabularies, but we know the discipline and sometimes practice it.

To keep low is not to put ourselves above others but to know our own need to be reformed each day. To keep low is to be teachable and open to the workings of the Spirit—both in times of retirement, and in the lessons that come in our outward lives. To keep low is to be taught by everyone we meet: children, bus drivers, the folks who disagree with us in meeting for business, government officials.

We know this practice. It is at the core of Quaker business process. Keeping low says that we look for ways to learn together, to integrate our piece of truth with others’ pieces of truth. It is more exacting than compromise. It is the practice that can lead to miraculous moments when the Light of disparate bits of truth combines to illuminate a previously unseen path.

Even though we know this practice, we have trouble doing it. We can forget this discipline right in the midst of meeting for business, and we can really have trouble with it out in the world.

To keep low is not to be too sure we’re right but to seek the divine spark in those with whom we have strong disagreements, whomever they may be—including George W. Bush and Osama bin Laden. To keep low is not to proclaim our superior understanding of diplomacy, economics, or justice. To keep low means not letting our egos freeze us in an arrogant position, acknowledging that our position is flawed and that we are striving for a fuller truth.

The miracle of keeping low, repeated so often in Quaker lore, is its power of disarming our opponents with our compassion and willingness to learn. It is a critical and exacting discipline for those who would be peacemakers.

Discernment

This term has become common among Friends in the past several years. I remember that when I first heard it I thought it an awfully pompous way of saying “figuring out the right thing to do.” Since then I have come to treasure it as a spiritual discipline that requires the spiritual disciplines of retirement, prayer, living in the Cross, and keeping low.

First generation Quaker Isaac Penington wrote in a letter, “It is not the great and main thing to be found doing, but to be found doing aright, from the teachings and from the right spirit. . . . A little praying from God’s spirit in that which is true and pure is better than thousands of vehement desires in one’s own will and after the flesh.” Lao Tzu taught, “Do you have the patience to wait till your mud settles and your water is clear? Can you remain unmoving until right action arises by itself?”

Discernment is crucial in difficult times when we want to do something that will make a difference. In the frightening time building up to World War II, Thomas Kelly wrote of the “particularization of my responsibility in a world too vast and a lifetime too short for me to carry all responsibilities. . . . Toward them all we feel kindly, but we are dismissed from active service in most of them. . . . We cannot die on every cross, nor are we expected to. . . . The concern oriented life is ordered and organized from within. And we learn to say No as well as Yes by attending to the guidance of inner

responsibility.”

Strong, Supportive Spiritual Communities

Our work in the world is strengthened when it is nourished in the Quaker community. The teachings of those who have gone before lift up a standard for us to strive toward. Courageous and faithful people in our own meetings become models and mentors. Our meetings for worship call us to retire and attend to discerning guidance for our lives. Our meetings for business are a laboratory for learning to put our own wills on the Cross and to keep low and be teachable.

Clearness committees and oversight committees, at their best, embody deep spiritual disciplines. Meeting with the committee draws us away from our busy pursuits into retirement. Settling into prayer helps to open to the possibility of divine guidance. Keeping low is embodied in the very act of submitting one’s discernment to a clearness committee. And openness to the incisive questions of the committee can put one’s will on the Cross and produce an outcome quite different from what the person seeking clearness was expecting.

As we aid one another in discernment we grow closer to one another and to the Source. Not only is the individual strengthened, so also is the meeting. Mary Rose O’Reilley, a Friend in Minnesota, wrote, “If someone pays attention to that part of me that struggles to know God, my search intensifies. If someone believes with me in the amazement of grace, prays with me, and reminds me of God’s tenderness, I live more fully in sacred time.”

Can we pay attention to that part of one another that struggles to know God, bringing one another to the amazement of a grace that will give us strength and stamina for the times we live in?

George Fox seems to have known the heart of our times when he wrote: “Looking down at sin, and corruption, and distraction, you are swallowed up in it; but looking at the light that discovers them, you will see over them. That will give victory and you will find grace and strength; and there is the first step of peace.”

——————

©2003 Patricia McBee