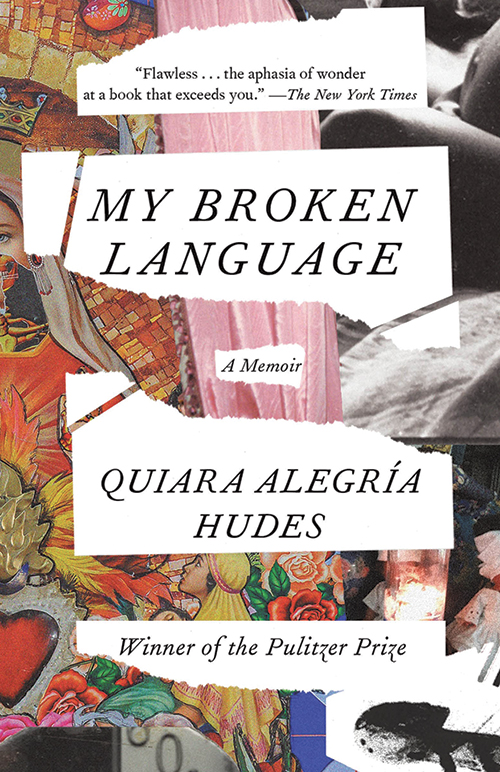

My Broken Language: A Memoir

Reviewed by Carl Blumenthal

April 1, 2022

By Quiara Alegría Hudes. One World, 2021. 336 pages. $28/hardcover; $18/paperback; 13.99/eBook.

Here’s what I wrote in “Worship for a Dummy” for the Brooklyn (N.Y.) Meeting newsletter:

After 20 years of speaking in Meeting for Worship, I realized in 2012 that my messages were coming from the bottoms of my feet, not the depths of my soul. That’s when I took a vow of silence. I’ll take my blessings off air, as callers do on talk radio—the ones who listen rather than sermonize.

This hasn’t helped me center down any better. I look around at Friends meditating without distractions, wishing I could do the same. If I were a pearl diver searching for divine treasure, I would come up empty-handed every time.

In her memoir, My Broken Language, Quiara Alegría Hudes (whose book for Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical In the Heights gained a Tony nomination) describes similar struggles to center down in a meeting for worship she attended at Central Philadelphia (Pa.) Meeting when she was a teenager.

But then she is shaken by the Spirit and shares her memory of a visit with her mom and pop to seaside caves in Puerto Rico where they encountered Taíno petroglyphs: “Here was Boriken before empire, before crucifix, gunpowder, or smallpox and maybe before English or Spanish. Here was the way Taínos spent their time: carving the numinous world in stone.”

So, what were the chances that the daughter of an Afro Rican mother and Jewish father would find her way to Friends? (Well, how likely is it that I, a Jewish guy, would have three Quaker girlfriends and marry a lapsed Catholic-Lutheran in the meeting where I was an attender?) Hudes grew up in a Philly Puerto Rican neighborhood; went to a magnet high school where she rubbed elbows with young Friends. Her mother, Virginia Sanchez, worked for American Friends Service Committee as an ambassador to teens of color. Although she never became a member, Hudes married Ray Beauchamp in the same meeting she attended.

Hudes’s possession by the Spirit at Quaker meeting is one of four epiphanies in the book. The other three are like epileptic fits in which she has no memory of what she wrote: for an essay test in high school; a playwriting exercise at Brown University; and half of The Adventures of Barrio Grrrl!, her first production.

Undoubtedly, having witnessed her mother’s possessions as a Santería/Lukumí priestess had something to do with these youthful “initiations” because, once Hudes found her voice as a writer who incorporates elements of these rituals in her plays, the epiphanies ceased.

Her memoir ends before she became famous, not just for In the Heights (she also wrote the screenplay for the recently released movie), but also part of a trilogy, Water by the Spoonful, which won a Pulitzer Prize and was based on her cousin’s experience as an Iraq War vet. In fact, her dozen plays and musicals have autobiographical roots that can be unearthed in My Broken Language.

While the title refers to her shame that she is more fluent in English than Spanish (as well as shame that, after graduating from Yale in music composition, she failed to make it as a rock star), it is ironic because Hudes’s language is as rich as the soil in her mother’s plant garden, and music is often in the background, if not the foreground, of her dramas. My Broken Language is so filled with psychological, spiritual, social, and political insights that any page chosen at random is enthralling.

In addition, she thrives on conflict. Like many of her plays that consist of short scenes in which incongruous actions are juxtaposed, her memoir contains 35 chapters in four parts, proceeding from childhood when her parents split and her “invisible” high school years to her time at Yale and Brown Universities, the academic refuges that taught her to embrace her Boriken American fate.

She especially embraces her female relatives who move two steps backward into poverty, addiction, and death for every step forward Hudes takes. Only someone who is empathic about her family’s and community’s pain would question her own sincerity while celebrating others’ resilience.

That she is lighter-skinned than her kin is one example of her relative privilege. That her dad’s sister, who worked with the Big Apple Circus’s orchestra, taught her piano is another. And that her self-taught mother convinced Hudes to become a professional writer is a third.

That White Friends were imprisoned for our beliefs before we enslaved Hudes’s ancestors and then became abolitionists proves—as does My Broken Language—imagination and Spirit form a bridge between who we are and who we want to be.

Carl Blumenthal is a member of Brooklyn (N.Y.) Meeting and was an arts reporter at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle for 15 years. “Worship for a Dummy” is one essay in Carl’s A Quaker’s Guide to the Cosmos that you can get for free by emailing [email protected].