The History of Laing School

The bold 26-year-old Cornelia Hancock came from rural Southern New Jersey and started Laing School in 1866 in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. At that time, she was probably one of a handful of Quakers in the Charleston area and in the whole state of South Carolina. She came, following her calling by God. A nurse during the Civil War, she had cared for soldiers during some of the biggest, bloodiest battles, including Gettysburg, the Battle of the Wilderness, and the Siege of Petersburg. When she landed in the Charleston area in 1866, one year after the Civil War ended, she probably stood out like a sore thumb. This was at a time when hostilities between the North and South were still very high. But Hancock was not about to be stopped by any attitudes about “Yankees” and “n— teachers.”

Quaker organizations were the primary source of funding for Laing School from 1866 to the 1940s. Cornelia Hancock ran Laing School for ten years, working closely with the occupying Union Army and the Freedmen’s Bureau stationed in the town for needed resources. She was a prolific letter writer, and from her letters, we learn about Black soldiers stationed in Mount Pleasant and aspects of life during Reconstruction in the area. The 160-plus year history of Laing is very rich and quite dramatic. Hancock was replaced by Abby Munro, a missionary from Rhode Island who ran Laing for 37 years. During her tenure, the school was heavily damaged by a hurricane, and then one year later, it was totally leveled by an earthquake. The Quakers, who never seemed to fail to meet the needs of Laing, financed the construction of a new school.

Left: Four Civil War nurses present at the fiftieth Gettysburg reunion. From left to right: Clarissa Jones Dye; Cornelia Hancock; Salome Myers Stewart; Mary O. Stevens. Middle: Cornelia Hancock (1840–1927). Right: Cornelia Hancock outside a tent at the Virginia hospital encampment in the winter following Gettysburg.

The school is named after Henry Laing of Philadelphia. Laing was a Quaker and an abolitionist. He was the treasurer of two Quaker organizations that funded the school (Friends Association for the Aid and Elevation of the Freedmen of Philadelphia; the Pennsylvania Abolition Society). In the 1800s and early 1900s, many of the teachers at “Freedmen Schools,” such as Laing, came from the North and were away from their homes and families. Henry Laing took special care of the school’s teachers, getting them the books, materials, and resources they requested. When he died in 1899, there was a very heartfelt memoriam in the school’s newsletter acknowledging him as a loyal friend and patron of Laing School.

During her 37-year tenure, Abby Munro initiated the Laing School Visitor, which was the school’s newsletter. Each month, she would list the names of people who had sent supplies or money to the school. The supplies would be shipped in barrels. For example, in November 1899, 36 barrels of clothing, school, and cobbling and dressmaking supplies were sent to Laing. In addition, $382 was sent to support the school. Several of the cash donations given were in the amount of one dollar. Most of these donations came from Quakers in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York.

The eight principals that followed Cornelia and Abby were one group of tough men and women: dedicated, persevering, and wonderful educators. They picked up the baton from those two ladies; never dropping it; and continued to run the race, oftentimes in the face of difficult odds.

Left: Abby Munro, 1846. Right: List of contributors to Laing School, November 1899. Abby Munro Papers 1869–1926. South Caroliniana Library Collections, University of South Carolina.

One of the more important aspects of Laing’s 160-plus year history is the great love and pride that the students and the community felt for this school. It served as a sanctuary for our ancestors as they faced discrimination, disappointment, violence, and seemingly insurmountable challenges. I went to a Laing School, as did my mother and my grandfather. As a child growing up in the Old Village of Mount Pleasant, I remember my mom, aunties, and the elders talking about Laing School. The laughter and fond memories that were a part of those conversations gave you a sense of their great love for the school. Today it is my cousins, my friends, and I who are having those conversations with the joy and the laughter. Our conversations continue to convey the love and the pride people have always felt for a school that was such a great blessing to Mount Pleasant for so many years. Laing School continues today as a nationally recognized, integrated middle school that focuses on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Laing’s story is unique, but it is also representative of the thousands of freedmen’s schools that were built after Emancipation. There was a very powerful movement of Americans who collaborated with the freedmen to build schools. The Quakers were very much a part of that movement. They had a very special relationship with Laing, but they were also involved in building and supporting many other schools, including historically Black colleges and universities.

During the Civil War, 500,000 enslaved people ran away from southern plantations to freedom behind the lines of the Union Army. This flow of people into so-called contraband camps created an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. The Quakers played an integral role in providing relief for these newly emancipated people in those camps. The Freedmen Schools Movement was born in those contraband camps. Quakers were also fierce, determined abolitionists. After reading about their history, I have concluded that they were led and used by God to help a people gain freedom.

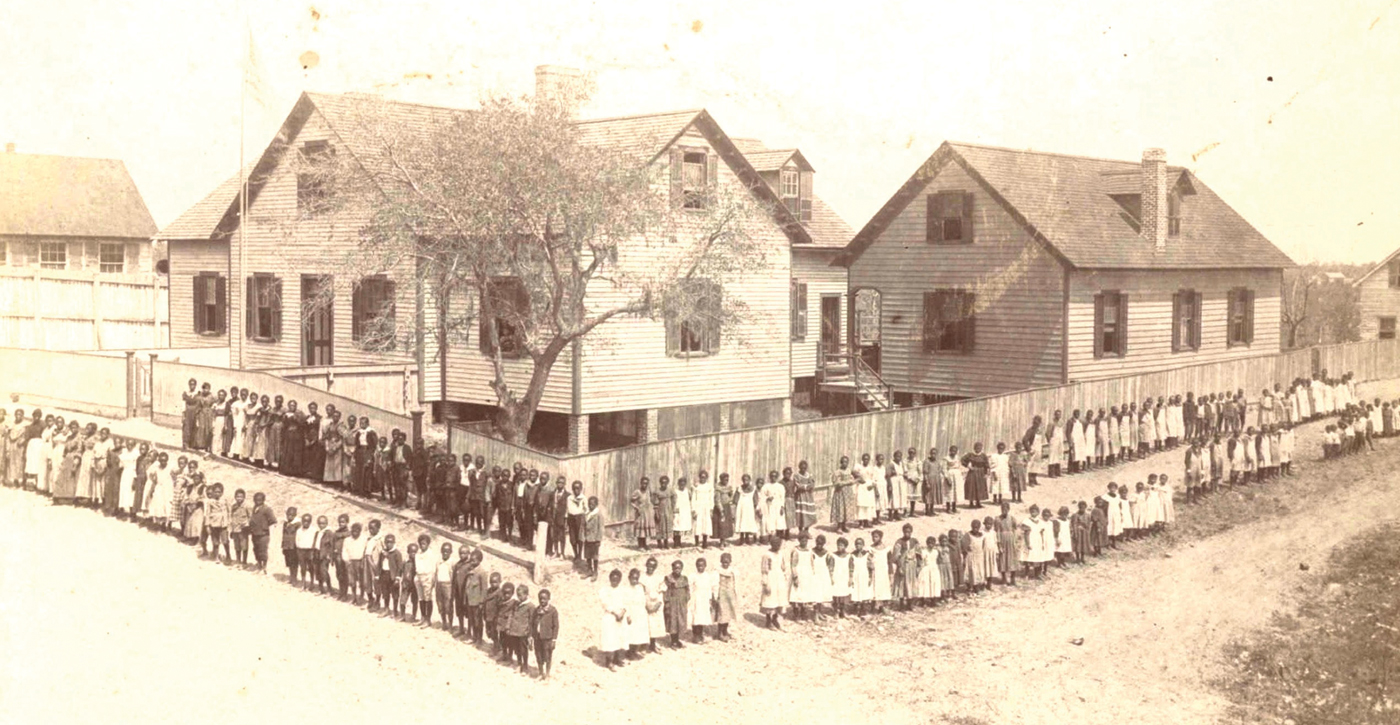

Left: Children in the schoolyard, taken between 1868–1886. Abby Munro Papers 1869–1926. South Caroliniana Library Collections, University of South Carolina. Right: Mirriam Brown, one of the three female trailblazers who led Laing School over the course of 160 years.

If you search for Cornelia Hancock’s name, you will see that she is known and celebrated for nursing soldiers during the Civil War much more than for starting a school in South Carolina. But to the thousands of descendants of the enslaved from the many plantations in Mount Pleasant, the legacy of what she started at Laing matters most. Most of the people from the old Laing School era are gone or are in their 70s. The last class of the old Laing High School graduated in 1970. The challenge now is whether the rich history of this school and other Freedmen Schools will be preserved.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.