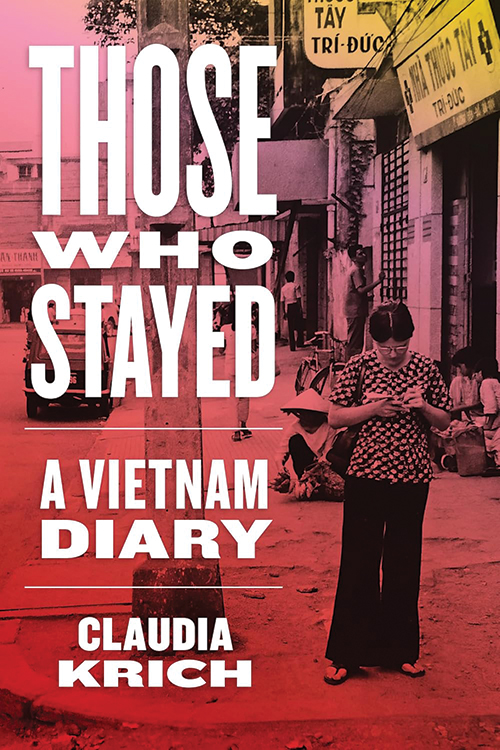

Those Who Stayed: A Vietnam Diary

Reviewed by Robert Levering

October 1, 2025

By Claudia Krich. University of Virginia Press, 2025. 304 pages. $34.95/hardcover or eBook.

Quakers are well-known for our peace testimony. For many Friends, this testimony translates into refusal to participate in war or making war, as well as active opposition to wars. In both world wars, Quakers played outsized roles in helping civilians impacted by the carnage. In 1947, American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) and the British counterpart, Friends Service Council, were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their relief work.

Less well-known is AFSC’s humanitarian work in Quang Ngai province during the Vietnam War. Quang Ngai is one of the poorest areas of the country and the scene of some of the heaviest American bombing and intense fighting. My Lai, where in 1968 U.S. troops massacred hundreds of civilians, is located only five miles from where AFSC operated a medical clinic and a rehabilitation center for amputees, many of whom were children who had stepped on landmines or unexploded bombs. The government provided prosthetic devices for military amputees but nothing for civilian victims.

Though I’d heard of the Quang Ngai project, I had no idea how dangerous and heroic AFSC’s work was before I read Claudia Krich’s account in Those Who Stayed. Krich, who while “not raised Quaker” says she “was attracted to active pacifism as a sensible philosophy,” and her husband, Quaker Keith Brinton, were codirectors of the AFSC program in Vietnam from April 1973 to July 1975. At that time, I was on AFSC’s national staff and was organizing nonviolent protests against the war. I naively—or more accurately, arrogantly—thought that humanitarian work was sort of a cop-out, not as crucial as the work those of us were doing in the streets. How wrong I was.

The 30-page prologue, “Before Sài Gòn,” provides background context and details challenges AFSC staff faced while in Quang Ngai. Although U.S. ground troops had left Vietnam by early 1973, the war raged on. The villages in Quang Ngai were typically controlled by the South Vietnamese government during the day but after dark by the National Liberation Front (NLF), which was also known as the Viet Cong. AFSC staffers were constantly reminded of the ongoing war and frequently heard gunfire and bombings.

Three of the staff were abducted by NLF soldiers when they inadvertently ventured into NLF-controlled territory. Convinced of their neutrality, their captors released them after 12 days. Rick Thompson, a Quaker draft resister, died in a plane crash en route to Quang Ngai from Saigon, where he had traveled to deliver two patients for surgery. Krich tells stories of coping with repeated robberies, a flood that inundated their clinics, and dealing with corrupt government officials and drunken soldiers.

By early April 1975, Krich and the other AFSC staffers realized they could no longer remain in Quang Ngai. The North Vietnamese Army was overrunning city after city to the north and would soon reach Quang Ngai, and so she and three others left for Saigon. The 22 chapters of Those Who Stayed contain her dated journal entries (supported by letters and other firsthand sources) for the three months she remained. This includes an account of April 30, when North Vietnamese Army tanks took over the Presidential Palace marking the fall of Saigon—or the liberation of Vietnam, as viewed by the victors.

Krich and her AFSC colleagues were among the very few Americans or Westerners who were in Saigon to witness these events. Her book is especially valuable because she was fluent in Vietnamese and interacted with a wide variety of people, including soldiers of the conquering army. In general, these soldiers and the political cadres who became officials of the new government behaved politely and respectfully toward the populace. Krich’s account demonstrates that the frequently repeated American and South Vietnamese government predictions of a “Communist bloodbath” proved to be overblown propaganda.

Krich does not, however, write as a cheerleader for the new government. She recounts the scary final days of the war and frustrating dealings with newly installed and often disorganized government officials. She also tells of an avaricious landlord, thefts of their bicycle and cameras, trials of getting around the city and obtaining food, and a betrayal by a former clinic worker. She also conveys the joys and fears of ordinary Saigonese as they face a new world: one without war and a corrupt regime but with an unknown new administration. It’s a fascinating story that is told engagingly and entertainingly.

I visited Vietnam for the first time this spring and was especially disturbed to see that the Vietnamese are still coping with the legacy of what they call the American War. For example, 17 percent of the land is still uninhabitable—and will be for decades to come—because of the massive U.S. bombing campaign. And people, mostly children, are still losing limbs because of unexploded bombs or are suffering from the effects of Agent Orange. My group visited two facilities that are carrying on the work of healing the wounds of war that was performed by Krich and her AFSC colleagues half a century ago. That is a legacy that we as Quakers can look to with pride.

A member of Santa Cruz (Calif.) Meeting, Robert Levering was a full-time organizer with American Friends Service Committee and other peace groups during the Vietnam War. He is the executive producer of The Movement and the “Madman,” which premiered on PBS in 2023 and is now streaming on Prime Video.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.