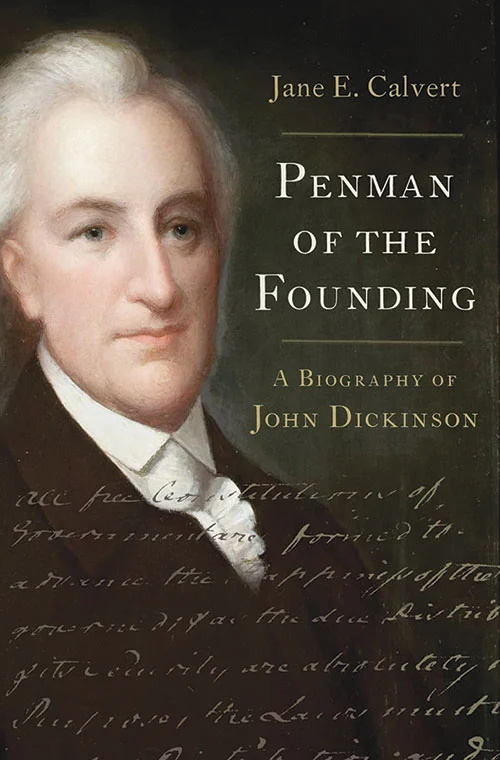

Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson

Reviewed by Signe Wilkinson

November 1, 2025

By Jane E. Calvert. Oxford University Press, 2024. 608 pages. $35/hardcover; $23.99/eBook.

The Fairhill area of North Philadelphia is generally known for its dense, mostly rundown housing; poor residents; and its crime and drugs. Three hundred years ago, it was a lush part of William Penn’s “greene country towne” and the area where John Dickinson (lawyer, statesman, prolific polemicist, and Pennsylvania’s president from 1782 to 1785) built his family’s estate.

In a new biography, Penman of the Founding, author Jane E. Calvert has resurrected Dickinson’s reputation as one of early American democracy’s most brilliant, influential, and now almost unknown founders. Calvert, a professor of history at the University of Kentucky, is currently the foremost Dickinson scholar, having studied him for over two decades. She is the founding director of the John Dickinson Writings Project, which since 2010 has been working to assemble and publish the entire corpus of Dickinson’s political and legal works.

Dickinson was born in 1732 to a wealthy Quaker father and enslaver of people who worked their huge plantation nearby the shores of the Chesapeake Bay. He was liberally educated by private tutors at home in addition to being schooled in the Bible by those who thought that, “Though God was infallible, men were not. The teachings of the Bible, therefore, were not to be viewed too narrowly.”

Friends Journal readers will be interested in why Dickinson never managed to become a Quaker even though he was born to wealthy Quaker parents; married a Quaker; and followed many core Quaker tenets in his business, politics, and family life. In various ways, he put Quaker ideals into action more boldly and constructively than most of the birthright Quakers who largely stayed out of the politics of the day.

Calvert writes that Dickinson was a religious dissenter: dissenting from Quakers. “Although raised as a Quaker and deeply religious in Quakerly ways, he disliked organized religion.” He rejected some aspects of Quakerism and felt that “[j]ust because someone dressed plainly or used ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ did not, alone, make him a good Quaker, obedient to God’s will.”

He did, however, bring his Quaker beliefs into his growing participation in colonial politics. In the face of tightening British control, Dickinson wrote:

We claim our rights from a higher source [than British law], from the King of kings, and Lord of all the earth. They are not annexed to us by parchments and seals. They are created in us by the decrees of Providence, which establish the laws of our nature. They are born with us; exist with us; and cannot be taken from us by any human power, without taking our lives.

The 1765 Stamp Act followed by the British Townshend Acts, both of which infringed on the colonists’ liberties, spurred Dickinson to start writing his wildly popular series of essays under the pseudonym “the Pennsylvania Farmer.” Calvert writes that Dickinson’s own experience with Quaker governance on the model of monthly, quarterly, and yearly meetings led him to think something similar could work for civil government. Not everyone agreed. Thomas Paine, in his usual calm, well-reasoned prose called Quakers “a fallen, cringing, priest-and-Pemberton-ridden people.” (“Pemberton” was a reference to Dickinson’s wife’s politically powerful cousins.) Despite Paine’s attacks, Dickinson’s Farmer essays were widely read throughout the colonies and throughout Europe.

By 1777, Dickinson was ahead of his time on slavery: becoming the first of America’s founders to begin freeing his enslaved persons with a conditional manumission; he manumitted his remaining enslaved persons unconditionally in 1786. In his 70s in 1805, he was still “impatient” for the end of slavery, Calvert writes, but others had by then become more outspoken. On this and other moral issues of the day, Calvert writes of Dickinson, “time and again he risked reputation, fortune, life, and limb by speaking truth to any power placed over him and by fully enacting his principles in his public and private life.”

Today, Dickinson is mostly forgotten. Philadelphia area Quakers are, however, unknowingly carrying on his ideals. A hearty group of Friends has been working for over 30 years in Fairhill, now a poverty-stricken North Philadelphia neighborhood. The nonprofit Historic Fair Hill cares for the historic Quaker burial ground where Lucretia Mott and other Quaker reformers are buried; they clean surrounding blocks, tend community gardens, and volunteer in local public schools.

John Dickinson would approve.

Signe Wilkinson is a member of Chestnut Hill Meeting in Philadelphia, Pa. She served for seven years on the Board of Trustees for Friends Publishing Corporation. In the 1990s, she helped to clean and restore the badly deteriorated Fair Hill cemetery.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.