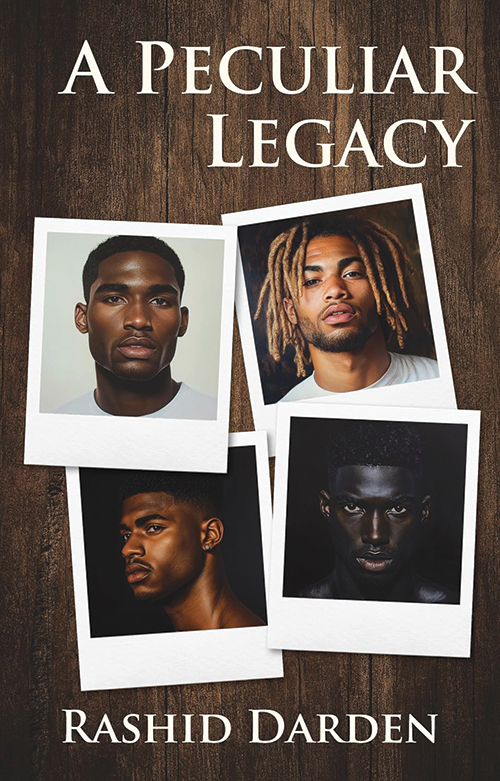

A Peculiar Legacy: A Novel

Reviewed by Abigail E. Adams

September 1, 2025

By Rashid Darden. Old Gold Soul Press, 2025. 192 pages. $15.99/paperback; $8.99/eBook.

This novel opens with news of the fatal street shooting of Gino, a young Black man. He is one of four friends from Slope, a small and tight-knit (fictional) Black neighborhood in Washington, D.C. The year is 2022. Gino moved to Slope with relatives five years earlier, escaping his mother’s violence. He flourished there; earned his GED; and worked toward a future with his girlfriend, Dana. Hours before Gino was shot dead, his mentor and the alternative high school program director helped him enroll in university. He planned to leave the corner drug-dealing that funded his hopes. The killer remains at large (no spoilers!), but other mysteries quickly emerge that will further engage readers, as author Rashid Darden, a Black Friend and award-winning novelist from D.C., unfurls the tragedy’s consequences.

Slope’s residents gather every Sunday morning on Slope’s main street for what appears to be worship in the manner of Friends. Every Sunday morning, able-bodied volunteers block the street with barricades. People bring out chairs. A teen recites the welcoming words that open Friends weddings and memorial services. People settle. Worship closes when neighborhood elder Miss Sandra shakes hands with those next to her. She invites all to Sunday dinner.

How did this faith community begin? And why on the street?

Not until further in the book is Slope’s worship connected to Quakers. Miss Sandra responds to one visitor’s inquiry: “I guess. I don’t know nothing ‘bout no Quakers, though. Ain’t no Quakers in Slope. Any church is alright with me as long as they are all about love.”

Like Gino’s murderer, the practice’s “peculiar legacy” remains unnamed until we the readers learn more about the relationships and lives grounded in Slope, including those surrounding the book’s third mystery and the title’s double entendre. Peculiar, known as “Peek,” is the youngest of the four friends. He submits consumer DNA test results and hears from a “cousin,” an older White woman in rural North Carolina. His elder, Pops, won’t tell Peek the family history behind this interracial connection. Peek grasps that it is a painful history for his Black Slope relatives, but he also hears the warm excitement of his newfound White cousin. Peek longs for his ancestral story.

Darden has written more than a mystery: he movingly portrays a community, the four young men, and others at the heart of this tragedy. It’s a portrait of D.C. beyond the mall, museums, and politics. Through Slope’s Miss Sandra, we learn that the neighborhood, a long-standing utopia for so many, was imperiled by 1980s crack, 1990s gang violence, and mass incarceration. Now she despairs, as she “sees” its young people as “ghosts” in a “graveyard,” pretending to be alive. A mentor warns one of the four boys, “Never be fooled by this city. You see Black folks and think you home. You ain’t home. None of this was built for you. It was built by you, but it ain’t for you.” Gentrification and displacement seem on their way to Slope when a gay professional couple buys a foreclosed house.

The new couple, however, join in the community’s worship. They, along with other neighborhood adults, step up to comfort and lift up the community’s grieving “ghost” youth. Darden details the many ways that Black men care for the young: fathers and grandfathers, men dealing drugs to secure their families’ living, the gay man who reaches for his estranged children, and the alternative high school director who ceaselessly champions his charges.

Another Slope resident, the detective Royce, theorizes that the Sunday meetings create a hallowed space in Slope’s center, in the street, and this is perhaps the reason it remained homicide-free. During one Sunday meeting, the book’s central tragedy reaches its climax, with love making the first motion.

I loved the descriptions of that faith community, its intergenerational worship and Sunday dinners. A similar warmth, respect, and joy drew me to Friends as a teen. I resonated with how Ziggy, another of the four friends, found “the silence. It might be as challenging as a Where’s Waldo? book, but in time, he always found the silence.” When Miss Sandra defines discernment as “those feelings inside her that were already so complete and powerful that God must have put them there,” I yearn for her spiritual confidence.

Throughout the book, we learn that many in Slope have experiences with Quakers through individual Friends, meetings, weddings, even Friends camp. White members of Friends Meeting of Washington (D.C.) come to worship in Slope and are welcomed. But Slope’s renewal, the answers to its mysteries and challenges, will not come from Friends, Friends testimonies, or historic examples but from the power of community members and allies joining together in their peculiar legacy.

Abigail E. Adams is a White Friend who worships with New Haven (Conn.) Meeting. She grew up in the D.C. area, returning for a young adult year to lobby with Friends Committee on National Legislation (FCNL) in 1988–89. She returns regularly to the city, including for service with FCNL.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.