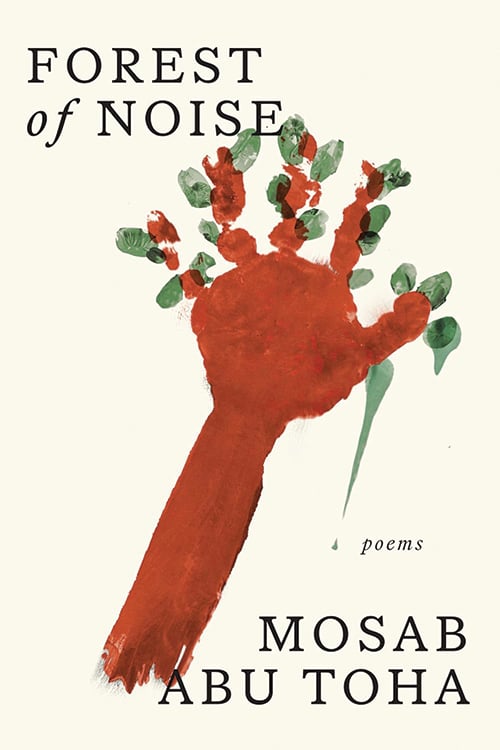

Forest of Noise: Poems

Reviewed by Catherine Wald

October 1, 2025

By Mosab Abu Toha. Knopf, 2024. 96 pages. $22/hardcover; $12.99/eBook.

Mother forgot the cake in the oven,

the bomb smoke mixed with the burnt chocolate

and strawberry.

This imagery from the poem “Thanks (on the Eve of My Twenty-Second Birthday)” speaks to me about the ordeals of life in Gaza more powerfully than would any statistic. It’s about ordinary people trying to do ordinary things—schoolchildren playing soccer, grandfathers dozing in the sun, a family drinking tea together—until they are interrupted by bombs or drone strikes.

Forest of Noise, Abu Toha’s second book of poetry, was named a New York Times Notable Book. His first, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza (2022), won the American Book Award and the Palestine Book Award. At 32 years old, he’s also won a Pulitzer Prize for his “Letter from Gaza” column for The New Yorker. Earlier in 2017, he founded the Edward Said Public Library, Gaza’s first English-language library; the building was destroyed by Israeli bombs in 2025.

Youth has nothing to do with depth of experience, Abu Toha stresses in “Younger than War,” the first poem of this collection. At age seven, watching bombs fall near his home, he says he was “decades younger than war, / a few years older than bombs.”

Born and raised in refugee camps, Abu Toha was able to come to the United States with his wife and three children partly because his youngest son is a U.S. citizen; Abu Toha was also offered a fellowship in the MFA program at Syracuse University. Still, he almost didn’t make it: en route to the United States via Egypt, he was forced away from his family at a military checkpoint by Israeli soldiers, stripped, beaten, and detained for two days. The poem “On Your Knees” recounts this event in spare language that doesn’t fail to express the terror of the situation.

Living a relatively safe life now, Abu Toha never fails to remind us of all he has not escaped: loss of home, country, relatives, friends, his own childhood, and his sadness that a grandfather’s early death meant the two never met. Too, there is the very real fear for family and friends who remain behind.

No matter how lyrical and tender Abu Toha’s language may be, there’s always a punch in the gut somewhere along the way. The poem “We Are Looking for Palestine” invokes “sea waves [that] lap against the shore . . . [and] glitter and dance with the fishers’ boats,” but it ends:

We no longer look for Palestine.

Our time is spent dying

Soon, Palestine will search for us,

for our whispers, for our footsteps,

our fading pictures fallen off blown-up walls.

In another poem, “My Son Throws a Blanket over My Daughter,” the poet’s four-year-old daughter, wearing a pink dress, gasps when a bomb explodes in her neighborhood. Her older brother, at the mature age of five-and-a-half, covers her with his blanket. “You can hide now, he assures her.”

This collection taught me much about the warm family ties, daily routines, and traditions of Palestinian life. I understood more deeply: not only about lives lost but about how deeply traumatized survivors are and have been for decades—by death, terror, and hopelessness.

Readers will be moved, educated, and perhaps galvanized by Abu Toha’s Forest of Noise, which reaches beyond the realm of political events to a far more human level.

Catherine Wald is a poet who lives in New York City and worships at Morningside Meeting.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.