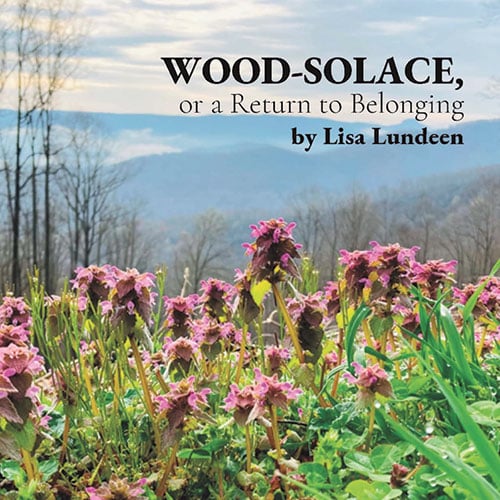

WOOD-SOLACE, or a Return to Belonging

Reviewed by Neal Burdick

November 1, 2025

By Lisa Lundeen. Plants and Poetry, 2023. 138 pages. $25/paperback.

At first glance, WOOD-SOLACE, or a Return to Belonging seems an odd title for a collection of photographs and poems. But once I realized that the keystone topic of the book is healing and what healing brings us back to, it makes sense. Nature is a source, perhaps the best source, for the process of healing, start to finish. The hyphen in WOOD-SOLACE unites the pieces and binds them together: the physical, the social, and then the spiritual. As Lisa Lundeen writes in her title poem, “I myself became part of the wood again, welcomed home as though I had never left.”

Lundeen comes from the “Quaker tradition of sitting in quiet, expectant waiting for the sacred to draw close.” A graduate of Guilford College and Earlham School of Religion, she lives in Greensboro, N.C., where she is a clinical healthcare chaplain. Her poems have been published in Friends Journal and other periodicals, including the poem “Plants and Poetry”—the title of which illustrates the intersection of nature and art, particularly the art of writing. This is an intersection Lundeen has long pondered, come to know intimately, and mapped in detail, but not so much as to prevent the rest of us from choosing which way to turn and marking our own pathways.

It’s hard to say which came first: the photos or the poems. That’s a chicken-and-egg thing. While a marriage of the two forms of expression, image and word, is not unique, in Lundeen’s imaginative ignition, that combination becomes more closely autobiographical than most. Whereas many poetry collections can be absorbed in any order, WOOD-SOLACE is most effectively traversed like a prose book: page by page, one after the other, in order. The sequence follows Lundeen’s roller coaster ride through life—up, down, up, down. The four section titles convey this ragged hill-and-hollow journey: Desolations, Ruminations, Consolations, and Celebrations.

Lundeen’s photography is centered in the world of botany. Her pictures—one per two-page spread, each opposite a corresponding poem—reveal the realities of the natural world, mostly as recapitulated in the continent of flowers but also via moths, honeybees, ripe apples, frothing brook waters, and spider webs: delicate yet resilient, hard and soft, tough but vulnerable. As we study these images, we realize they are us.

And so we begin with Desolations, in a hopeful echo of life’s phases to come with the poem “A Cry for Spring”: “I long for days of consolation / . . . and green bright petals . . . / Calling us into our own centers.”

The following accompanies a picture of a desiccated, shrugged-off snake skin on a slab of rotting tree bark:

I long to live in skin

That is just the size to hold my

Sinew, bone, and deep-down hopes,

Strong and smooth as I

Make my way through the

Undergrowth another day.

Most of Lundeen’s work is blank verse, but rhyme appears once in a while. A spiny saguaro cactus inspires the thought “If not peace, may my / worship bring release.” As we progress through the book’s sections and life ascends, her poetry becomes more rhythmical, more lyrical, more smoothly structured, and calmer. Consider these observations from “A Leading, My Child” in the section Ruminations: “A leading is what draws the oak from the acorn . . . what calls the caterpillar to spin a cocoon. . . . A leading, my child, gives you wings.”

As we near the final section, Celebrations, things are really looking hopeful: “A Few Instructions for Finding Your Way” advises: “Look through cobwebs / and dust for fresh shoots / of potential, opportunity.” Finally, in that section, all is well: “The Gift of Blessing Another” begins, “To bless another is to incubate their vitality” and ends, “To bless is to send out, to call in, to fling potential, to honor blossoming, to soothe and embrace.”

Quakerism is not here verbatim, but it infuses all of Lundeen’s work, whether it be photographs that demonstrate respect for all living things, regardless of how “correct” they look, or verbal allusions to light, simplicity, and openness. With often startling imagery, Lundeen urges us, whether dealing with the natural sphere or the human, to see “a relationship rather than a document,” and when we achieve this level of perception, “do you allow yourself / to burst into flame?” Read this book and you just might.

Neal Burdick’s poetry has been published in Friends Journal as well as vastly more obscure outlets. The poetry editor of the Adirondack Mountain Club’s magazine Adirondac, he attends Burlington (Vt.) Meeting.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.