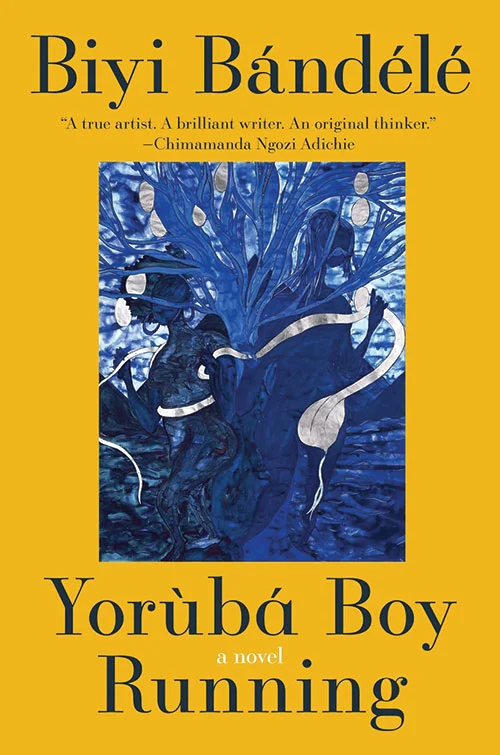

Yorùbá Boy Running: A Novel

Reviewed by Margaret Crompton

November 1, 2025

By Biyi Bándélé. Harper, 2024. 288 pages. $26.99/hardcover; $11.99/eBook.

“Àjàyí!” exclaimed my Nigerian friend Philip Omogbai, on seeing the photograph of the Reverend Samuel Crowther that appears on the penultimate page of this extraordinary novel. Friendship with Philip’s family had stimulated my interest in reading it. The book provides background for understanding about religious adherence, slavery, and the country we know as Nigeria. However, I would not have sought such enlightenment through a textbook. The lure for me was the enticing title Yorùbá Boy Running: A Novel.

The narrative is an imaginative biography of nineteenth-century Reverend Samuel Àjàyí Crowther (1809–1891). As a young boy, Àjàyí was captured, sold into slavery by Malian (Muslim) traders, freed, educated, converted to Christianity, and ordained. He was a brilliant linguist, became a missionary and abolitionist, and the first African Anglican bishop. He met Queen Victoria.

Nigerian-born Biyi Bándélé, who died shortly before publication at the age of 54, was a pioneering novelist, playwright, and filmmaker. Many narrative forms and traditions—including stories, songs, lists, uninhibited dialogue, and Crowther’s own eloquent writings—evoke the complexity of his subject’s life. Àjàyí is a man of faith, love, and grace in a world of violence, oppression, and explicit sexuality.

The first fast-moving chapters vividly present the boy’s life immediately before capture. Bándélé’s writing is as direct as the language of the drums: “Yorùbá was a tonal language; what they did with their talking drums was to perfectly mimic the tone and rhythm of everyday speech. There was no conversation too complex, no thought too difficult, to express with a talking drum.” Philip read aloud the Yorùbá transliteration of one drum dialogue, bringing both language and raunchy tale to life and reminding me of Chaucer’s storytelling pilgrims in The Canterbury Tales.

The title of the novel itself and part one, “Run, Àjàyí, Run,” refer to the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I in which a short ballet enacts the tale of Eliza. The original story in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin tells of Eliza, an enslaved woman escaping with her child. The phrase “Run, Eliza, run!,” shouted by the ballet chorus, represents the struggle for freedom.

While Eliza’s story depicts the struggle to run from oppression and toward freedom, Àjàyí constantly confronts challenges. Even when his life is threatened, he understands “there was nowhere to run to; he was surrounded. He stopped—he had no choice, really—and turned around to face the king. Better die standing.”

However, his greatest challenge comes not from an African monarch but an English religious organization. In his 80s and “blessed with unbroken health,” the bishop, Reverend Crowther, is forced out. The Church Missionary Society (CMS) sent what Bándélé calls “two operatives . . . both ravenously ambitious and fragrant with righteousness, to talk down to him and humiliate him in order to elicit his resignation from . . . his bishopric.” Bándélé doesn’t hold back in revealing their motives:

They were assassins and, like all assassins on a mission from on high, they struck without remorse. Their mission was an unqualified success; he resigned . . . and was instantly replaced in the post with a white man, their intention all along. It was the beginning of a wholesale cull of all traces of the African presence in positions of authority within the CMS in West Africa.

Àjàyí responds with courage and grace but suffers a fatal stroke. This scene reminds me of times white Quakers have failed Friends of Color throughout history. I think about nineteenth-century Friend, educator, and writer Sarah Mapps Douglass, for example, who experienced racism so blatant within the Quaker meetings of her day that she often wondered “in [her] own mind, are these people Christians?”

In response to his father’s ousting, Dandeson Crowther, Archdeacon of the Niger, removes the churches in his own jurisdiction from CMS control and founds the Niger Delta Pastorate Church, the first independent Church in West Africa: “‘I will have nothing to do,’ Dandeson said, choosing his words carefully, ‘with those who cannot see that all men are created equal before God. It’s a sin.’”

In his introduction, the Nigerian author Wole Soyinka writes: “We all knew the Àjàyí story, of course—right from elementary school”—I think of my friend Philip’s immediate recognition of him in the photograph. Soyinka praises Bándélé’s work: “The humanity hidden behind the unsmiling portrait . . . comes to life . . . combative, learned, warmly human, even with a touching sense of humour. It has taken a writer armed with a matching diligence to flush him out.”

Through Samuel Àjàyí Crowther, two great writers challenge us to learn and to confront assumptions and prejudice with humility, courage, honor, and grace. Run, Quaker, run to the bookstore.

Margaret Crompton is a member of Britain Yearly Meeting. Her publications include Children, Spirituality, Religion and Social Work (1998) and the Pendle Hill pamphlet Nurturing Children’s Spiritual Well-Being (2012). She has written and directed plays for a small drama group. Recent publications include poems and short stories.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.