A Quaker Witness in the West Bank

This past April, I visited Ramallah with a group of eight people from the United States and England who assembled with the common goal of serving as a Quaker pastoral presence for the Ramallah Friends School (RFS) community during these difficult days.

While there our team was invited to attend a presentation by several RFS tenth-grade students who had recently completed a collective project on cultural mapping in the West Bank of Palestine. The assignment introduced the students to the research techniques of cultural mapping, a methodology that involves identifying and documenting the tangible and intangible cultural assets that exist within a local landscape. Four teams of students had been dispatched to four small villages in the countryside around Ramallah. The project involved observing what life is like in the villages and, most importantly, talking to the people who lived there, with the goal of helping them to uncover and recognize the resources in their villages. In my view, the assignment also helped the young students grow and develop their own identities as world citizens and as Palestinians.

At the presentation, four different students reported on the visits of the teams to each of the four villages and summarized their findings. One of the presenters began his report by saying something like this: “In this village, the Christians and the Muslims are the same; there is no difference.” He did not elaborate on this statement, and I was not totally sure what he meant. I would not have been surprised to hear that the two groups simply avoid each other, that there is a constant low-grade dislike of the other’s religion, or that the main goal of each group is to change or convert the other. I heard none of that in the young man’s presentation, and I wanted to know more.

After the presentation ended, I had the opportunity to talk with the young man, whose name was Waseem. He told me that the first people their team spoke to in this village were the priest, an Orthodox Christian, and the imam. The basic message they heard from each of these religious leaders was, “We are friends! We spend time together! Our congregations do things together! We celebrate each other’s festivals!” This was really good news to hear. In many cases where different religions are involved, the report could have been the exact opposite.

I told Waseem that I had been thinking about the Quaker testimonies, especially the testimony of equality, and how I think equality seems like a foundational principle or the gateway to all the others. Without a sense of the inherent worth of others, without recognizing our shared humanity despite different backgrounds and opportunities, without seeing that of God in every person, what kind of peace can people build? How could people create true community? And how would integrity be affected by an imbalance of equality?

The young people at RFS live in a land under occupation where equality is out of whack. In just the last 20 years, a high wall that currently spans 288 miles has been built between the West Bank of Palestine and Israel. In the last 30 years, checkpoints have proliferated. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, between the West Bank and East Jerusalem alone, there are 13 checkpoints; only three of these can be used by Palestinians who hold West Bank IDs and Israeli-issued permits, which are difficult to obtain. Besides walls and long lines at checkpoints, there are other kinds of movement barriers scattered throughout the West Bank that make travel slow and difficult.

Over 600,000 Israeli citizens currently live in settlements within the West Bank, but they do not come to Ramallah to shop. The settlements are interconnected by very nice highways, so the residents can move easily around the area and travel quickly to larger places, like Jerusalem, and they use quick checkpoints. Palestinians are not allowed to use these nice roads, and the roads themselves are part of the movement barriers because places to cross the roads are limited.

In addition to the daily reminders that equality is far from reach, many Palestinians have experienced other forms of injustice, and there is a lot more violence against Palestinians in the West Bank than most people realize. For me, the following often came to mind: “The situation is worse than I thought.” World opinion about the Palestinian predicament depends on people of the world helping to shift the narrative, and we are living in a critical moment.

Gaza City is a mere 51 miles (calculating by a straight line) from Ramallah. The ongoing horrors taking place in Gaza are on everyone’s minds all the time. I heard one person say that he has never been more concerned about what could potentially happen right there in the West Bank.

Our team met Father Fadi Diab, the rector of St. Andrew’s Anglican Church. He told us that in Ramallah, they do not have enough programs dealing with psychological well-being or with trauma. He said that young people often ask with strong emotion, “What can we do?” Then the realization hits them that they can do nothing. Fr. Diab went on to say: “Hope is how you change yourself. Working with or helping someone worse off than you is a powerful act to help you deal with the rage in you. Hope is not something you think, but something you do.” He then said we should all orient ourselves toward constructive—not destructive—actions. These are the only means to help us in these times.

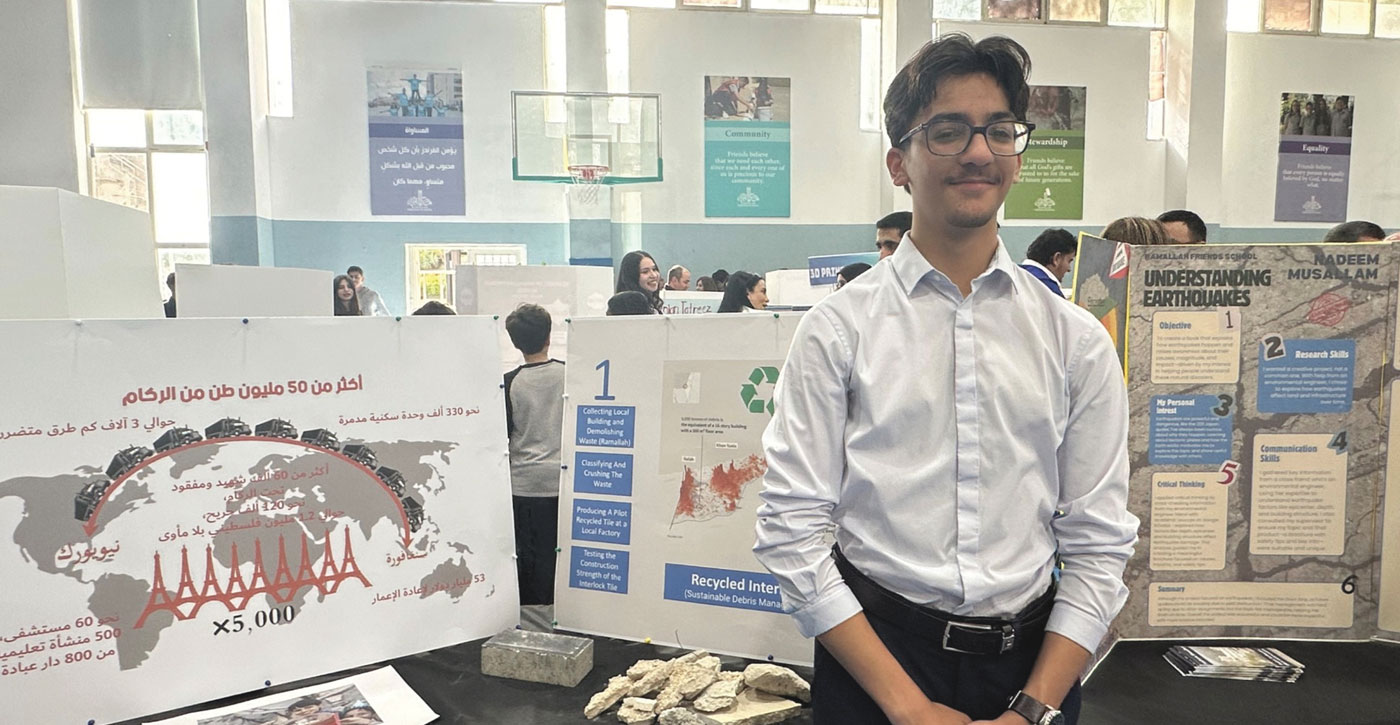

I met students who are also growing hearts of compassion for others. In addition to the collective project of cultural mapping, each of the tenth-grade students also had an individual project. These were on display toward the end of our time in Ramallah. One young man named Zaid had a chart based on data from the UN estimating that as of December 2024, there were over 50 million tons of debris from nearly 70 percent of structures that had been damaged or destroyed in the Gaza Strip. Zaid proposed that the debris be crushed further and recycled into new interlocking bricks that could be used to rebuild Gaza after the war ends. I was deeply moved by that conversation. Among the dozens of other student projects, I noticed that quite a number of them also had helping people in Gaza in mind.

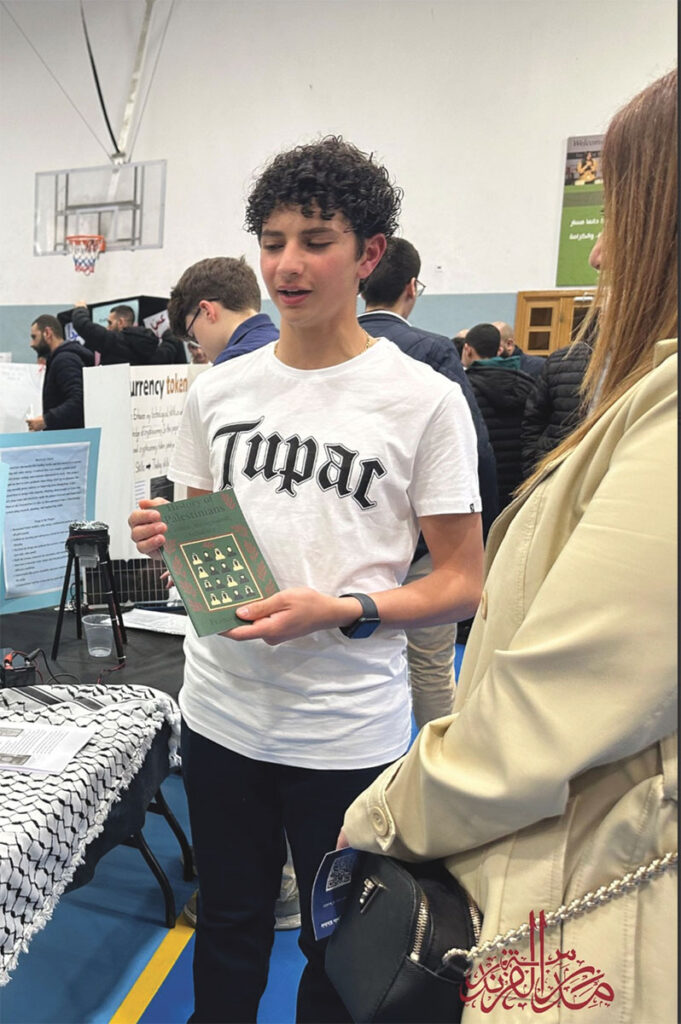

Another student, François, wrote a booklet featuring profiles of Palestinians who have made an impact on the world, from educator and activist Edward Said to rising singer Elyanna and many others. At the beginning of the booklet is a poem by François addressed to his fellow Palestinians in Gaza, whose lives have been devastated, “But Whose Light Remains.” It ends with words of solidarity: “In Resilience, / In Love, / And In the Longing for Liberation.”

Our friends in Palestine face uncertainty about the future, as well as daily indignities related to living under occupation. Despite all this, we encountered young people who were moving full speed ahead, forging for themselves the hopeful and happy futures they long for and that they deserve.

I am frequently brought back to the thought of the friendship between the priest and the imam in that little village, and their two congregations celebrating each other’s festivals. It’s a small picture of the world we long for. There are so many things in life that are beyond our control. This example of acceptance, friendship, and joy reminds us that there are also a lot of things that are entirely under our control and that can make our world a better place.

Thanks for this. My prayer is to have fairness to humanity in West Bank that the wall can be dpne away spiritually.

Thanks Cliff Loesch. The small village integration can light the world.

Did none of the ‘illegal’ 600,000 Jews live within the Ramallah Friends School’s tenth grade project area?.