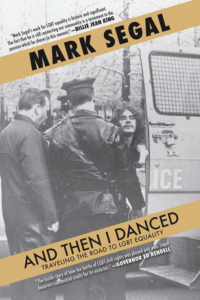

And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality

<h4><b>Reviewed by Mitchell Santine Gould</b></h4>

October 1, 2016

By Mark Segal. Open Lens, an imprint of Akashic Books, 2015. 320 pages. $29.95/hardcover; $16.95/paperback; $16.99/eBook.

By Mark Segal. Open Lens, an imprint of Akashic Books, 2015. 320 pages. $29.95/hardcover; $16.95/paperback; $16.99/eBook.

Buy from QuakerBooks

Just how bad was life for gay people in 1978? Mark Segal recalled that when his beloved mother died, he ran into his uncle Ralph at the funeral. This uncle had seen Mark quoted in the obituary as calling his mother “a gay activist,” and, once he verified that Mark had really said that, Ralph concluded: “Then maybe it’s good that she’s gone.” I can recall this as a time in which one could shock an entire cocktail party into petrified silence by uttering the words “gay” or “homosexual” aloud, and the stigma of having simply mentioned those dread words would then follow one for years, even sabotaging a career. And that was years before the international AIDS hysteria, a time when people were afraid that if they touched a gay man, they would be infected by an incurable disease.

Segal’s book has been described as part autobiography, part history lesson. He grounds the history with a moving glimpse into the lives of his struggling but dignified, and, in their own modest way, heroic parents. The historical sections recount Segal’s clever interventions to save America from its addiction to hate, and to empower strait and gay allies who were ready and eager to help but were just waiting for an opening. (I use the spelling “strait,” which has the connotations of being restricted, to reject the superiority automatically assumed by heterosexuals.) Time and again, Segal found a way to provide that opening in the vast wall of silence.

Segal was a poor Jewish kid from a Philadelphia housing project when he personally witnessed the famous riots of oppressed patrons at Manhattan’s Stonewall Inn, a gay bar, in 1969. Each Fourth of July, from 1965 to 1969, strategists such as Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings had been dressing in business formal to picket for gay rights in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, in protests known as “Annual Reminders.” They were out to convince Americans that gay people were respectable citizens who posed no threat to society. But Segal, shortly after his arrival in New York, joined the Gay Liberation Front, which adopted a radically different, in-your-face attitude, modeled on the nonviolent actions of the Civil Rights and Women’s Rights movements. Segal became known for “zaps”: stunts to draw media attention to that one topic which, for a thousand years, had been precisely defined as “not to be mentioned among Christians.”

Most famously, on December 11, 1973, Segal used a pass given to journalism students to visit the set of Walter Cronkite’s news program. He crept onto the stage, and blocking out Cronkite’s face, sat on the anchor’s desk, and held up a sign before millions of American viewers: “Gays Protest CBS Prejudice.” It was an electrifying turning point, launching Segal as a key spokesman for the movement and even turning Cronkite into a significant mass media advocate.

Segal went on zapping, against the dreary backdrop of identity politics infighting (an illustration of Gould’s Fourth Law: good usually spends more time fighting good than it does evil). In time, he pioneered the vital institution of the local LGBT newspaper, publishing the Philadelphia Gay News, and then helped to establish the National Gay Press Association. His book offers several insights into his behind-the-scenes collaboration with Pennsylvania’s progressive Jewish governor, Milton Shapp, and goes on to chart his steep descent into depression, even as he became more influential and successful—in the eyes of the world. Fortunately, friends were able to turn him around before he succumbed to his hidden demons. Much later—four decades after he got booted off a TV dance competition for dancing with a man—in a brave and clever “media zap,” Segal and his partner danced at a gay pride fest in President Obama’s White House. That zap gave the book its name.

Quaker readers may find all the celebrity stalking and name-dropping off-putting. It’s true that celebrity photos document the very social change Segal was called to serve; still, it seems that the author could be more aware of what is endangered by a journey from exclusion to the ranks of privilege—indeed, to the ranks of the gatekeepers. But strait and gay readers alike frequently report that they find in Segal’s anecdotes a rich source of inspiration for nonviolent actions on behalf of social change, and I do not hesitate to recommend it.

Given that Segal is proud of his Jewish heritage and many of his collaborators shared that heritage, the book calls to my mind unspoken questions about the example of Jewish community as a social force for innovation, nurturance, and leadership. As an outsider, I am fascinated by the possibility that the rest of society may have something of value to learn from the fruits of their solidarity. In any event, And Then I Danced proves that we need more Mark Segals.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.