Guided by the Inner and Outer Light

Whenever someone I am meeting for the first time asks, “Who are you?” or something similar, I’m tempted to say, “I am a spiritual being enjoying an earthly experience.” It’s a clever phrase, not original to me but one with which I’m generally comfortable. However, I recently realized that I’ve never thought deeply about what it means: that is, until a photograph from Duane Michals’s sequence The Spirit Leaves the Body (1968) caught my attention. I’ve long been an admirer of Michals’s work, and this sequence of seven photographs has become one of my favorites. But like the phrase about being a spiritual being, I had never thought deeply about the ideas implied by this sequence of photographs. My reflection on the photographs has led me to a better understanding of what it means to be a spiritual being and has enabled me to order miscellaneous ideas I’ve thought, read, and even written about over the years. My realization was like what happens when the last turn of a kaleidoscope brings all the chaotic pieces of glass into a beautiful and coherent pattern. It has also led me to a new understanding of the Quaker concept of the Inner Light and the purpose of silent worship, which I find truer to my experience and more helpful to understanding my spiritual journey.

The Photographs

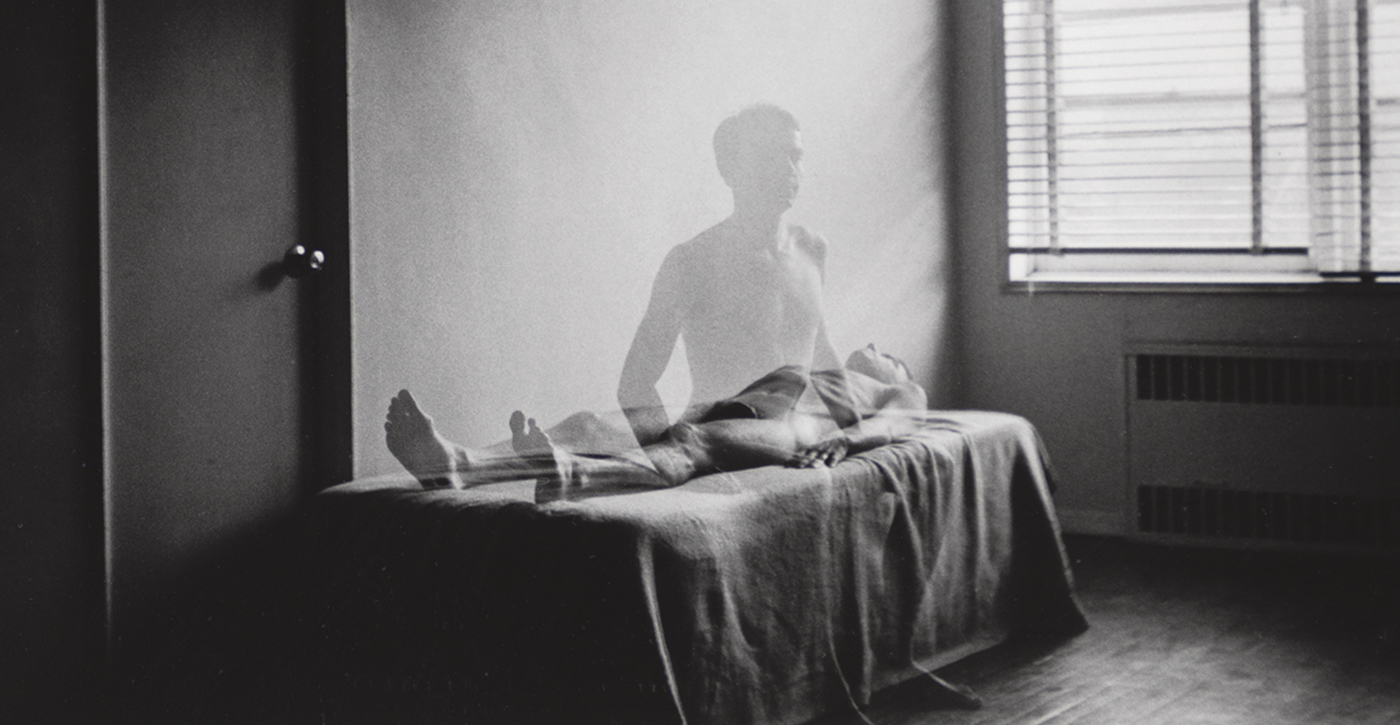

There are seven photographs in The Spirit Leaves the Body sequence. The first and last appear to be the same; they show the body of an adult man lying naked on a bed or a cloth-covered platform. In between these two are five other photographs that show the transparent figure of a ghost-like man superimposed on the image of the man lying on the bed. In the first, the transparent man is sitting up; then in the next, he’s sitting on the edge of the bed (my favorite photograph in the series and the one that prompted these reflections); then he’s moving toward the camera and becoming more transparent until he finally disappears. There is neither captions nor text, as there often is in other sequences of Michals’s work. We are left to figure out the meaning on our own.

The sequence suggests that each of us is composed of both body and spirit, a belief that permeates much of Michals’s work and one that I share. The question this particular sequence poses is this: Is the man in the first photograph alive or dead? You may not believe there is a Spirit at all, in which case this question is irrelevant. And even if you do believe, you may still think the question irrelevant: after all, when you’re dead, you’re dead; what difference does it make when the Spirit leaves the body? However, I think the answer to that question is key to how I view my life (and how to view yours) and how I view my death.

The second chapter of Genesis tells us that God created a human being from dust and then breathed into this inanimate object, thereby bringing it to life. I understand that the Hebrew word for “breath” can also mean “Spirit.” So that implies that God transferred some of Its Spirit, Its likeness, to the human figure, and as a result, “there is that of God” in each person. Whether I literally believe that this is the way life began is not important; it’s the spiritual concept that interests me. If at birth (and I don’t want to get into a discussion of exactly at what point I mean), the Spirit gives life to the body, then what happens at death? Does the body wear out, collapse, and die, and then the Spirit leaves? Or does the Spirit leave of its own accord—or is it called back by God—and having done so, having removed the source that originally gave life to the inanimate body, does the body then die? If I consider myself to be a spiritual being having an earthly experience, the answer is clear: the Spirit leaves, and then the body, no longer needed, dies. Consequently, in the first photograph, the man is alive, and in the last, he is dead. This understanding is what gives rise to my concept of what it means to be a spiritual being and what that means about my life and my death.

Duane Michals, The Spirit Leaves the Body, 1968. Individual images 3.5″ x 5″, gelatin silver photographic prints. Used by permission of Duane Michals.

The Concept

The Spirit, being an aspect of God, never dies. It is eternal as God is eternal. It passes from one body to the next, from one lifetime to the next, and comes into each with a specific purpose and a plan to achieve that purpose. Both the purpose and the means by which it will be accomplished—everything from the selection of our parents to the events we will experience and the people we will come in contact with—are determined before birth and ingrained in our subconscious. Likewise the knowledge of how to make our bodies function, consciousness, and so much more is embedded subconsciously in our DNA and in other ways we have yet to understand. There are no coincidences; nothing we experience is accidental; everything is purposeful. But because the knowledge of our purpose and plan are in our subconscious, we do not remember them ourselves. Instead, we are given two guides: one is what we as Quakers refer to as an Inner Light, and the other—to be complimentary—might be called an Outer Light: similar to the “Light” we mean when we say we are holding someone “in the Light.”

Both are guides; both have been entrusted with all the details of our purpose and plan, but each guides us in a different way. The Inner Light helps us to recognize the people and events that will lead us along the path that will provide the most spiritual growth we can achieve in this lifetime. The Outer Light leads us to the circumstances in which those people and events will appear.

How it does this, I do not know, but that it does this, I am certain from the experiences of my own life. I know I have never made a decision about any aspect of my life. All decisions have been made by some outside force, by the unexpected influence of people and events that appear by “coincidence” in my life at just the right moment and are really messengers sent to guide me on my way. My task is simply to recognize and accept the guidance I am given and follow the paths on which I am led without necessarily knowing why or to what end. (If you think this idea is crazy, look at your own life. How many decisions have you actually made yourself; how many have been determined by the unexpected and “coincidental” influence of other people and events?) But both Inner and Outer Light are merely guides. We are free to follow or reject their guidance as we please; the only consequence is that we will have to try to learn those lessons again in another lifetime.

The Purpose

In a general sense, the purpose of each lifetime is simply to advance along the path of spiritual growth. You might say it is analogous to the experience of being a student in school. You start in one grade and gain knowledge (one lifetime), then take the summer off (death), and then return to a higher grade (next lifetime) where you learn higher knowledge, and you proceed along this alternating path until you have mastered all the subjects and graduate. What are we as spiritual beings learning in these successive lifetimes on earth? I believe we are learning to perfect our spirit’s ability to love all creation unconditionally. Earth is our school, our learning laboratory, and the pleasures and desires of material existence are the deliberate means chosen by us before birth to help us develop the strength to overcome self-centeredness. Each aspect of our life provides a different kind of learning experience to enable us to perfect our ability to love unconditionally in all circumstances, with all people, and under all conditions.

We are given two guides: one is what we as Quakers refer to as an Inner Light, and the other—to be complimentary—might be called an Outer Light: similar to the “Light” we mean when we say we are holding someone “in the Light.”

The Inner Light and Silent Worship

All this brings me back to the concept of the Inner Light and the significance of silent worship. Historically, and even today, turning to the Inner Light for guidance is a core concept of Friends, almost as if that Light only comes on when we turn to it for assistance. But this is a misunderstanding; the Light is always on; we are always being guided in the direction of spiritual growth by both an Inner and Outer Light. There is no need to ask for guidance. The problem is we are so distracted by our own concerns, our own needs, and desires that we are not sufficiently awake and alert enough to see or recognize the guidance we are being given, except in rare moments. Our task is to remove these blinders, to awaken, which is the way Buddha described himself to the first person he encountered after his enlightenment.

The purpose of silent meeting for worship is to help us do exactly that: to learn to turn off the distractions; the constant self-absorption we have with our own ideas, needs, and desires; and to awaken ourselves to an awareness of the presence of God in our lives. When we can do that in meeting for worship, we often hear a message from within or from another person that gives a new insight. But to hear that message, we must be awake and alert: undistracted by our own thinking. We must give up our “own willing,” as Isaac Penington said, and be willing to accept the guidance we are given: the paths the Light illuminates. As I wrote in an earlier Friends Journal article (“Wait and Watch,” FJ June 2006), meeting for worship is about spiritual practice; it is an opportunity to learn how to be awake and alert so that in our daily lives the unobstructed Inner Light is able to help us recognize, hear, see, and accept the messages that come to us through the people and events that the Outer Light brings to guide us on our way. Rumi expresses this beautifully in the poem “The Guest House,” the last verse of which is “Be grateful for whoever [or whatever] comes, / because each has been sent / as a guide from beyond.”

Death

Death is not to be feared. Death is neither an end nor a final going home to God. It is a temporary visit, a brief summer vacation, before the spirit returns to the learning laboratory of earthly life to undertake the next lessons that will eventually lead it to perfection, to graduation: to merge with the Divine Intelligent Energy of the Universe (my definition of the word “God”) and to new non-earthly experiences likely to be more wonderful than we can imagine.

Well said.

Thanks for reading my article in Friends Journal and taking the time to add a brief comment. If you would like to see more of my spiritual writing take a look at my website. http://www.johnandrewgallery.com. If you see anything there you might like to read let me know and I’ll be happy to give you a discount on a purchase.

Peace be with you.

John

What a great piece I have read, it has resounded my thinking on Spirit matters.

Thanks.

Thanks for reading my article and taking the time to comment. All the way from Kenya — wow!

Peace be with you.

John

http://www.johnandrewgallery.com

This piece brings with it such peace. Thanks