A Reflection on True Safety

Many Mennonite homes in Harrisonburg, Virginia, had guns in the 1950s. No, we were not worried about “personal protection,” as most of my neighbors never even bothered to lock their doors. But we lived on the edge of farmland and were surrounded by wonderful state parks. Like most of my male friends, I grew up owning guns and looked forward to hunting season in the fall. I was totally comfortable around guns. I had been taught gun safety by an older Mennonite neighbor before I was allowed to buy my first rifle. The first and most important lesson was to never point a gun, loaded or unloaded, at another person. Guns were to be used for target practice until one learned to use them accurately, and then for hunting, carefully following safety precautions so that one didn’t accidently kill a protected animal or injure another hunter. Our Mennonite faith taught us that personal safety comes not from guns and locked doors but from personal relationships that can be built, even with one’s enemy, through integrity, trust, and vulnerability.

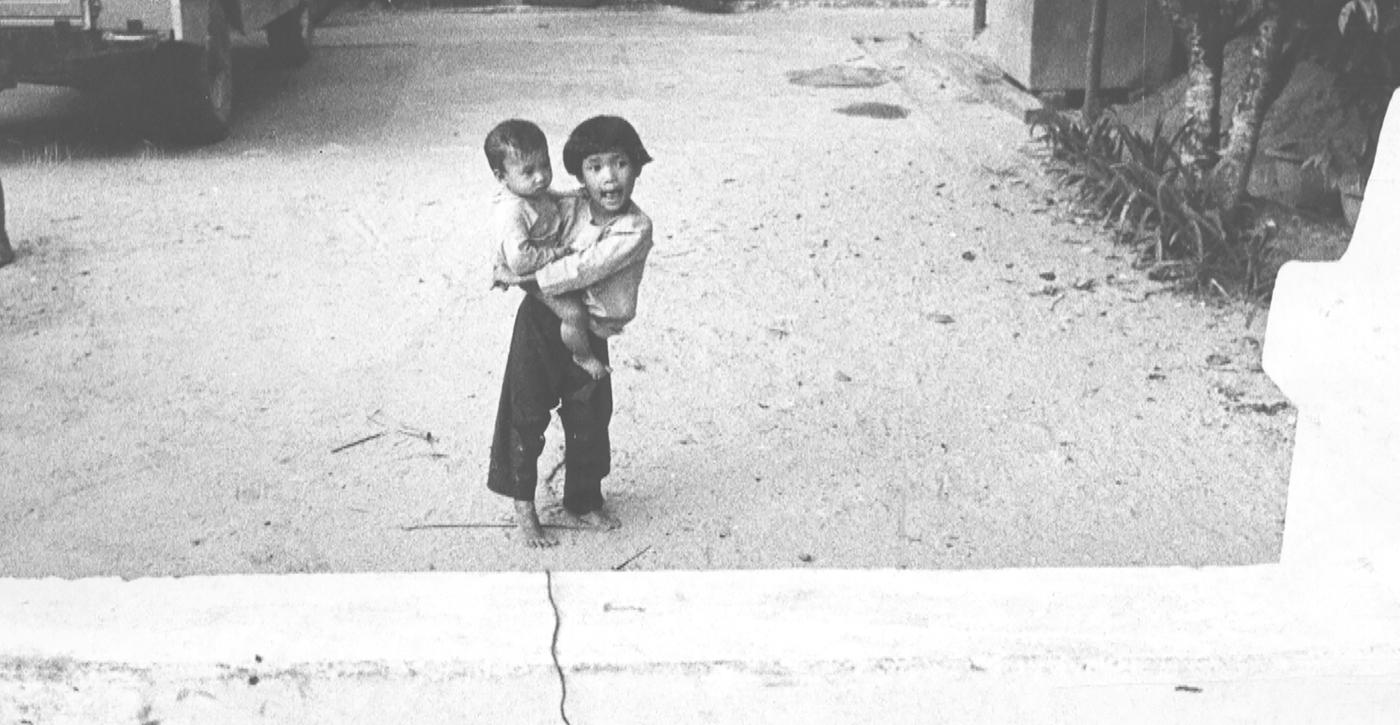

After graduating from Eastern Mennonite College (now University) in 1966, I filed for and received conscientious objector status. As this was the middle of the Vietnam War and men of my generation were being drafted and sent to Vietnam against their will, I felt it was only just that I volunteer to do my alternative service also in Vietnam but with the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC). MCC at that time was the director of Vietnam Christian Service (VNCS), which also included volunteers from Church World Service and Lutheran World Relief. I was assigned to start a VNCS unit in Tam Ky, Quang Nam, in central Vietnam where the heaviest U.S. military activity was taking place at that time. Our primary project was a literacy program that used 90 Vietnamese high school students to teach 4,000 refugee children how to read and write their own language after the schools in their home villages had been destroyed by the U.S. Air Force.

A U.S. Army M-114 155mm howitzer in Tam Ky, Vietnam, in 1968. Photo by the author.

Vietnam was a total shock to my system. I had grown up feeling very comfortable and safe around guns that were being used responsibly by neighbors for hunting. Now I was in a country at war with nearly a half-million American soldiers bristling with guns designed for killing other human beings.

I learned a lot about protection and guns during my three years in a war zone. When I had visited Tam Ky to explore whether VNCS should start a unit there, I had been informed by the American officials that the only safe place for me to stay in Tam Ky would be in one of the U.S. government compounds. There were three options: the Military Advisory Command, Vietnam (MACV); the CIA compound; or the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) compound. All three compounds were heavily walled and guarded with land mines and machine gun posts.

I stayed in the USAID compound but soon realized that I could not remain there. Vietnamese were allowed to come into and leave the facility during the day, but at night, all Vietnamese (except prostitutes) were expelled, and Americans were not allowed to leave in the evening. I realized that if I was there as a Christian peace witness to the Vietnamese people, I could not live in a U.S. government compound where I could not interact freely with Vietnamese. When I returned to start the VNCS unit in Tam Ky, I and one other VNCS volunteer moved into one of the dorm rooms of the local Catholic high school, which the priest had built for students whose homes were far from the school.

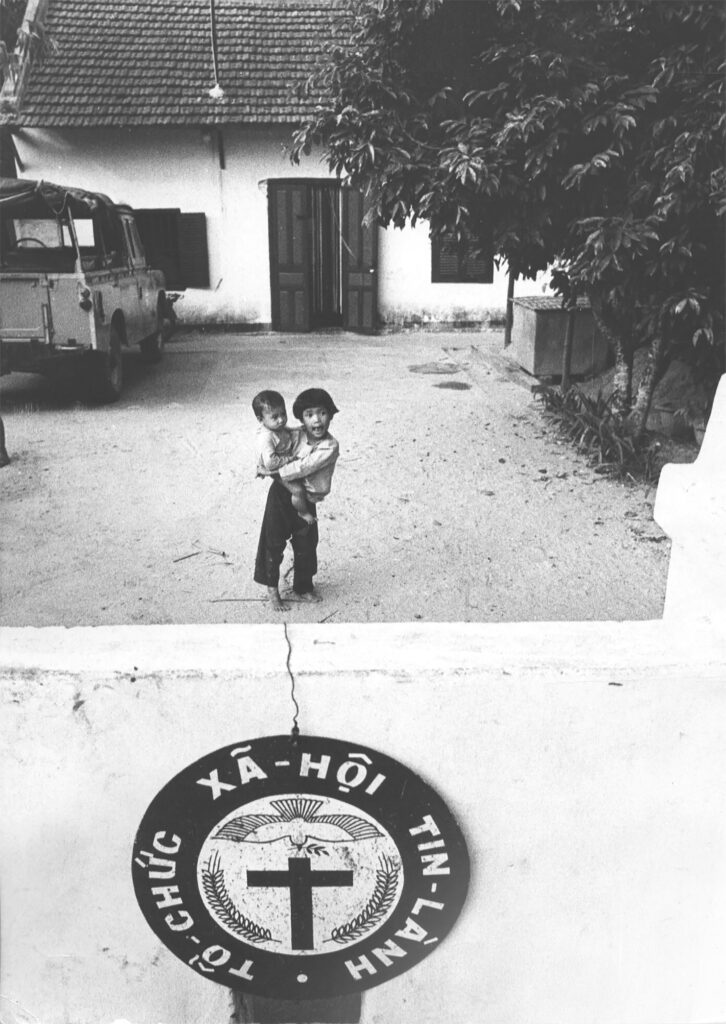

Unprotected wall around the Vietnam Christian Service house in Tam Ky, Vietnam, late 1960s. Photo: Mennonite Central Committee.

Eventually VNCS was able to rent a small bungalow across the street from the Catholic high school for our unit house. I will never forget the advice from the woman who rented us the bungalow. Mrs. An had explained that the National Liberation Front (NLF, or what the Americans called the Viet Cong, VC for short) would occasionally take over Tam Ky for a brief time. She pointed out that the house was only fenced in by a small four-foot wall, but told us we could add a steel gate, a few rolls of concertina barbed wire for the front and top of the wall, and a 50-caliber machine gun for the front yard to hold off the NLF until the U.S. Marines arrived to rescue us. No, I explained, that was not how we wanted to live. We never put a gate in that four-foot wall and everyone in the village knew that we had no weapons. Our only protection was a small sign that read “Vietnam Christian Service” (in Vietnamese) with a peace dove and a cross. The VNCS house was the only place in Tam Ky where Americans lived outside of a walled and guarded compound. I lived in Tam Ky for three years. The National Liberation Front took over the village (often for only a few hours in the middle of the night) about a dozen times. Each time the NLF entered Tam Ky, they attacked the heavily guarded MACV, CIA, and USAID compounds, but never attacked the VNCS bungalow, the one unprotected place where Americans lived.

I came to realize that most people in a war kill to keep the enemy from killing them first. When it was clear to everyone that we had no weapons and, in fact, could not even protect ourselves, we were no longer a threat: we were not feared; and many Vietnamese, on both sides of that war, became our friends.

My attitude toward guns has changed drastically since Vietnam. I have seen—up close and personal—the way military weapons destroy the human body. It astounds me that my country, or any nation, would allow civilians to purchase military-style automatic rifles like the AR-15 or the AK-47. These automatic rifles were specifically designed for war: to kill and or seriously maim people. Why would any government allow their sale to the civilian population, and why would any decent person want to own such a weapon? I am not philosophically opposed to hunting, and some of my brothers still hunt, but since returning from Vietnam, I have not been able to bring myself to reassemble my boyhood 22-caliber rifle, which I had carefully disassembled and stored before I left for Vietnam over 50 years ago. I do know, both from the Sermon on the Mount and personal experience, that true safety comes not from higher walls or bigger guns but from the refusal of weapons and hostility, which can enable trust and friendship whether with neighbors at home or enemies abroad.

Correction: a military historian informs us that the artillery in the photo is of M-114 155mm howitzer, which soldiers call “the Pig” and not a 105mm as we originally captioned it.

Thank you for sharing your story and perspective. More people who insist that firearms are necessary for self-defense need to read stories like this.

I personally am opposed to all guns, police and military included. As an ethical vegan, I do not condone hunting either. I hope that one day humans evolve into a truly peaceful species.

second amendment is unrelated to red herring references about hunting

it is in place as a deterrent to totalitarian domination of the common folk, the unhappy eventuality of all (or nearly-all) governments

if we can find a government without arms, we might be ok as a population without arms

(maybe could leave off shooting other species as well, at that point, but not holding our breath here)

your description of living peace in a war zone is persuasive; thank you

so far, i’ve managed to do the same, and retain some hope that existence itself is benign enough to allow for this

Doug Hostetter, you’re one admirable and compassionate SOB.

I was drafted into the Army and was in the country 1968-1969, and feel the same way you do now.

I get it (why people buy AR-15s); the power and thrill of firing an assault weapon in full auto mode is indescribable., but seeing the destruction they do to a human body puts me in your camp, against assault weapons being legal.

I don’t need to own any guns and haven’t touched one since leaving Vietnam.

Thank you for your story.