Reconciling with My Deceased Mother

How do you forgive a parent for a wound so deep that you don’t know where to begin? This is a story about reconciliation with and forgiveness of my deceased mother: a story greatly aided by my reading of Marilynne Robinson’s 2004 novel Gilead and some divine intervention.

My mother loved music and singing. She grew up speaking Mandarin, and today we would call her an athlete: she was a dancer, a tennis player, and a bicyclist. My vibrant, dancing mother is a person I barely knew because her life was disruptured and captured by what was then called “manic-depressive illness,” now referred to as bipolar disorder.

Reading Marilynne Robinson’s book Gilead transformed my relationship with my mother. The novel is a first-person narrative by a Congregational minister named John Ames. As Ames contemplates the afterlife, he is consumed by questions of love; reconciliation; and forgiveness, including how to forgive someone for a wound so unfathomable that he doesn’t even know where to begin. His questions, reflecting both book-learning and a sensual love of life; his tentative answers to ultimate questions; and his rejection of a pedantic faith that tolerates no mysteries resonated with my own theology.

Although the character Ames is not a Quaker, this query from British Friends’ Faith and Practice resonates deeply with the plot of Gilead:

Are you open to the healing power of God’s love? Cherish that of God within you, so that this love may grow in you and guide you. Let your worship and your daily life enrich each other. Treasure your experience of God, however it comes to you. Remember that Christianity is not a notion but a way.

And so, with these ideas working within me, I was inspired to write a prayer of blessing and forgiveness to my deceased mother. Here is the prayer, which I first shared with some classmates at the Earlham School of Religion in a class on creative writing and prayer in January 2020.

Lately, I’ve started to ask myself this question, “What would someone do if they knew, incontrovertibly, from their baby toes to their bangs, that they were loved unconditionally?” How would such a person walk in the world, shoulder their burdens, and move on from trouble? If I could imagine that sense of assured belonging, perhaps I could move that way. And so, perhaps could you, if there were any troubles to move away from in the Afterlife. I believe this is the message of 1 John 4:16 [ESV]: “We have known and believed that God loves us. God is love. Those who live in God’s love live in God, and God lives in them.”

I know now how ill you were and had been for at least a decade before I was born. And Dad, bless his patriarchal soul, would have been absolutely no help at all. How overwhelming it must have been to find yourself unexpectedly pregnant again despite “the Change” and your despair as you watched freedom from the daily tedium of child rearing recede far into the future. With that in mind, I can comprehend your distance—like a star from another galaxy whose light grew cold before it touched me.

I do have a few happy memories of you—I’ll share the one because I believe it was a particularly happy day for you too. You were, to use a Spanish expression that you wouldn’t know, “in your sauce.” We went, you, me, and Dad, to the World’s Fair in New York City. As saccharine as it sounds now and despite all the awful cliches with colonizing overtones, I was completely enchanted by the colorful, singing dolls in the Small World exhibit—and I wouldn’t hesitate to guess that’s one reason why I chose international relations as my vocation. But the absolute best part of the day for you, as I recall, was taking me to the Fair’s re-creation of a Belgian village where we ate thick, crusty waffles with sweet, juicy red strawberries, slathered with the highest airy mounds of whipped cream that I had ever seen in my whole, entire six-and-three-quarters years of eating in this world. And you were laughing and smiling and happy, enjoying a moment together with me.

If there were waffles in the Afterlife, I could pray that you might enjoy one now. But eating one alone, however majestic the setting, misses the point entirely. I might, however, tweak my question, “How might a person move through the world if she were buoyed by a memory of sharing a heavenly Belgian waffle with her mother?”

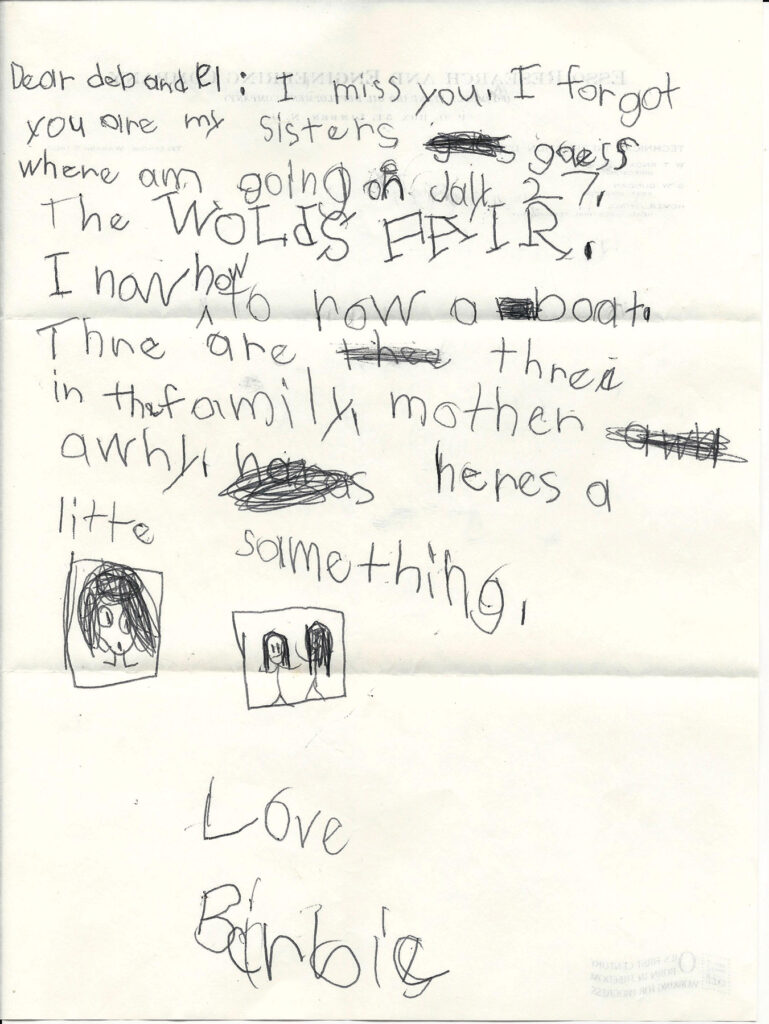

Returning home from class after reading my prayer of blessing and forgiveness, my inbox contained an unexpected email from my sister Deb that included a scan of a letter that I had written as a child and did not remember:

Dear Deb and El, I miss you. I forgot you are my sisters. Guess where [I] am going on July 27. The WORLD’S FAIR. I know how to row a boat. There are three in the family. Mother. Anyway (?) here’s a little something: [drawing of myself], [drawing of two big sisters]. Love, Barbie

I had written to my two big sisters, who were away at camp in the summer of 1964, to tell them I missed them. “I forgot you are my sisters.” The World’s Fair on July 27 was announced in all caps and an extra special font. The next day in class I told other students about this synchronicity. “Synchronicity is the secular word for it,” a fellow student said.

In her book In God’s Presence, theologian Marjorie Hewitt Suchocki talks about prayer engaging us in a relationship with God in which the nature of the enterprise has to take into account the world as it actually is. Inter-relational prayer is a way of working with the world as it is to create a world that “reflects something of God’s character.” An example of this is to pray for healing when death is certain and the spiritual healing that takes place cannot hope to restore a dying body. Prayers for healing, for example, are always constrained by the reality of mortality.

At the same time, with prayer, spiritual healing is possible for the dying and for those who will survive the death of a loved one, even when the restoration of physical health and well-being is not possible. Even death does not pose an insurmountable barrier to blessing and reconciliation. Nor does death heal the wounds of a fractured relationship.

My decision to write a prayer of blessing and forgiveness for my mother was an effort to locate where healing might happen. It has not always been possible for me to think of my mother, who was so shaped and constrained by bipolar disorder, in a positive light, even after her death. As a mother now myself, it is both easier and harder for me to imagine her condition and what her mental illness meant for her child’s life. Inspired by Marilynne Robinson’s language in Gilead and feeling a link to my maternal Congregational heritage, a prayer of reconciliation for our relationship seemed doable. In that prayer, it made sense to remember my mother at her best—during a day together at the World’s Fair.

My sister told me in her email that she had been thinking for a while about scanning that letter and had finally managed to get around to it that morning. My written prayer and the receipt of the letter from my childhood self the next morning feels like closing a circle that I never expected to close.

Robinson begins her novel Gilead with John Ames musing that the dead know everything there is about being dead but choose not to share. In the world in which my mother knows everything there is to know about being dead but is not able to share, I experience the mystical visitation from my almost seven-year-old self as an affirmation that my memory of that happy, intimate moment with her is both real and sacred. Words that might be empty or meaningless may later turn out to offer new insight into a relationship. In 1964, the word “mother” stood alone, isolated, and disconnected in that letter. Today, the word “mother” standing alone feels like an opening to her and from her. How could it be that this opening would occur right as I was praying about forgiveness in that relationship, and that the opening would arrive in the context of a letter looking forward to the very day in which my mother was wholly present with me? “Synchronicity,” as my classmate said, “is the secular word for it.” It is also evidence that God is love.

Thank you for this beautiful healing story!

Thank you for your essay, for this vivid story of God and synchronicity. Your essay resonates with my own prayer work in healing my relationship with my late mother, who suffered mental illness. I love that your forgiveness of your mother, and then the letter from your young self, formed a sort of call and response!