When the Allen’s Neck Clambake was organized 125 years ago on the third Thursday of August, a set of guidelines were handwritten in ink and framed and set within the great hall of the Allen’s Neck Meetinghouse on Horseneck Road in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

The site must be smooth and convenient.

One cord of dry hardwood in 4 foot lengths

One truckload of rockweed

One and a half tons of stones about the size of cantaloupe melon

All clambakes are not alike, they vary in menu.

Allen’s Neck always has the same menu. . . . . .

22 bushels Clams

30 pans of Dressing

200 pounds of Sausage

100 pounds Onions75 pounds Fish Fillets

20 large Watermelons

150 pounds Tripe

85 Homemade Pies

75 dozen Sweet Corn

50 pounds Butter

3 bushels Sweet Potatoes

Coffee

Milk

Special requirements-

A group of enthusiastic workers.

The clams must be culled and washed in fresh sea water in a boat at Horseneck Beach.

The sweet corn must be fresh and sweet-harvested the day of the clambake

The rockweed must be fresh and kept moist

Now the last and most important ingredient of all is to ask our dear Lord for good weather.

Clambake to feed 500 guests and 125 workers

The missive ends with a song “This was a real nice clam-bake.”

The tradition continues. However, today the Allen’s Neck Clambake is held under a grove of trees, and the soft-shell clams, quahogs, and fish no longer come from these shores. Meeting members originally set the date as a reliable time of year for the digging of clams and quahogs, the schooling of mackerel offshore, and the sweet corn harvest.

Nineteenth-century meeting members had quahog rakes and knew where and when to dig for the quahogs, which flavored the dressing, and the soft-shell clams for the bake. Today, many of the areas where the old timers used to dig are closed, contaminated, or altered. This is surprising considering the fecundity of the sea to offer up her bounty in the past. Historic photographs show a fisherman tonging for quahogs at South Wharf, and Friends Dave Ryder and Ben Gilley shucking scallops. Years ago the bay and estuaries were carpeted with eelgrass and bay scallops. Today the eelgrass beds are now sporadic and the bay scallops prove elusive.

The water quality in the shallows has been muddied by road and parking lot construction and the breaching of the Head of Westport upstream dams in the 1950s. Farm runoff; flocks of thousands of Canada geese; non-native cormorants; coastal development; and nitrogen and phosphorus washing from lawns, septic systems, and cesspools have provided fertilizer for invasive algae that has sealed the surface and shaded the eelgrass and killed the bay scallops.

Rotting algae carpet the estuary floor. Fast-moving boats stir up the shallow river and estuary like a blender. According to lifelong Westport riverman Chapin White, scallops spawn in the summer along with many estuary species of mollusk and fish. The larval bay scallops float with the currents for 48 hours before they settle down onto blades of eelgrass for safety from the crabs and other predators which lurk on the sandy bottom. There are thousands of boats registered in Westport and Dartmouth, not counting outsiders who use the boat ramps. Many of the boats have 200 horsepower outboard motors and can reach speeds of 40–50 miles per hour. According to Claude LeDoux, the turbulence creates wakes, scours the banks and stirs sediments. Any fragile species floating on the river or estuary surface is battered to death or smothered in turbid muck. Non-conservation boat mooring chains and buoys drag across the bottom re-suspending the rotting algal mud. Oil slicks can also be fatal to the newborn hatchlings floating in the estuarine algal soup. Some say that there are too many recreational boats on the shallow river and estuary to allow the shellfish and fish larvae to survive. The river and estuaries have changed.

The Westport River is slowly silting in. People with long memories, such as Alvin and his son Chapin White, Jim Pierce, Gus Gonet, and Claude LeDoux noticed the silting in of the streams feeding into the Westport River and the muddying of the river bottom. Buzzards Bay National Estuary scientist Joe Costa states that “the paving of the watersheds in the past decades has reduced the groundwater recharge and sped the volume of scouring runoff to feeder brooks, streams, rivers, and bays.”

It was not always this way: oysters, quahogs, clams, bay scallops, and surf clams allowed Alvin White to make a living on the river years ago. Alvin and Chapin would smelt in the earliest spring; set nets for the herring moving upstream; and fish for tautog, striped bass, bluefish, and swordfish in summer. They would oyster, clam, quahog, bay scallop, sea clam, crab, and eel year round; winter flounder in the bay; then frost fish and smelt in winter through the ice. A fisherman, if he worked hard, could provide for his family by fishing locally. Alvin worked seven days in the week.

When the Allen’s Neck Clambake entered into the 1940s and 1950s, Alvin and young Chapin traveled to Allen’s Pond on a moon tide. They barricaded a section of flats in the days when there were no regulations to stop the shell fishing, nor cormorants to foul the water. They started digging and, in the span of the tide, they collected 27 bushels of quahogs. Each bushel measured 32 quarts. Allen’s Pond was also habitat for bay scallops and oysters. Today, the pond has been fouled by the guano of hundreds of Canada geese and a colony of nesting cormorants that pillage the herring and other fisheries from bay to estuary to river, as they eat fish and eels and decimate the fisheries. Bay scallops were found at Allen’s Pond, Padanaram, and the estuaries of the western and eastern branches of the Westport River.

Ginger Pierce retells a childhood story of standing on a wooden bridge at Westport Point and watching the bay scallops swim by on an overcast night. The darkness was punctuated with hundreds of lights sparkling below the surface of the bay. At each opening and closing of their shells, startled bioluminescent organisms flashed a phosphorescent light that revealed the scallops’ 36 blue eyes staring back as the scallops swam through the bay. Dale Leavitt, a marine biologist and shellfish specialist at Roger Williams University, mentioned that scallops are sensitive to changes of salinity and turbidity and can migrate to more favorable conditions as a colony.

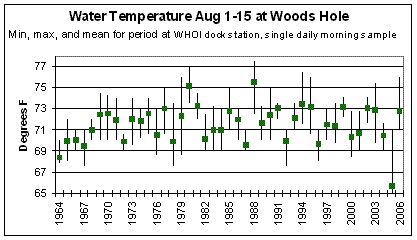

Years ago, I interviewed Gus Gonet who loved to follow the seasons on the shore clamming; quahogging; crabbing; scalloping; lobstering; and fishing for smelts, frost fish, blue fish, striped bass, and eels. His well-used tools speak to a life on the river, shore, and sea. Gus retold his fish tales as he held quahog rakes, wire clam baskets, eel spears, and frost fish lures in his weathered hands. Today, the smelt and frost fish no longer spawn in their natal streams. They have migrated to cooler waters and are functionally extinct in these waters. According to Brad Chase, a Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries marine biologist, the measurably warmer waters of Buzzards Bay may explain the absence of cold-water mackerel from these waters today. Mackerel can tolerate temperatures from 7° to 20°C (68°F). The average August water temperature for Buzzards Bay has exceeded this threshold since 1964 as graphed by the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program.

Climate Trends

The summer schools of mackerel are gone. Herring can tolerate waters to 10°C and can survive in 13°C water, but 20°C is lethal for sea herring. Smelt are even less tolerant of warming water and have abandoned Buzzards and Narragansett Bays. Global warming has affected the ocean’s temperature and marine biodiversity. Off the South Coast, temperature tolerant species and jellyfish are filling the void.

The summer schools of mackerel are gone. Herring can tolerate waters to 10°C and can survive in 13°C water, but 20°C is lethal for sea herring. Smelt are even less tolerant of warming water and have abandoned Buzzards and Narragansett Bays. Global warming has affected the ocean’s temperature and marine biodiversity. Off the South Coast, temperature tolerant species and jellyfish are filling the void.

In the past, many species of fish were overfished by foreign factory ships within sight of our shores. Sustainable fishery management was not a concern until the fisheries crashed in the 1980s and 1990s. Mackerel were decimated by domestic mid-water trawlers after the foreign fleets were phased out of U.S. waters in the mid 1980s. This stunted the population, but did not force an abandonment of off-coast mackerel migrations. The crash of mackerel, codfish, and herring were just three of the fisheries that were slow to rebound. There was a quandary how to codify the science with the policies to holistically protect the fisheries and their habitat. This evolved into marine-protected areas, seasonal closures for threatened species, and ecosystem-based management utilizing the trophic cascade principles. These questions are still being asked about how to manage the Atlantic fishery off of the coast. Mackerel are no longer on the menu for the Allen’s Neck Meeting Clambake. Yet tradition continues at the Quaker meetinghouse on the third Thursday of August.

Web Exclusive: Author video chat

Web exclusive: Photo gallery from recent clambakes

All photos in this gallery courtesy of the author

Web Exclusive: Allen’s Neck Meeting Clambake: A Fellowship of Friends

An article on the 2013 clambake by Joseph E. Ingoldsby.

I went to A N F M for 4 years or so in the 1980’s and 90’s. and then moved away from dartmouth. and i thank all the folks there for that time. yes, did volunteer at the clambake.

Hope to drop in next summer when I visit Dartmouth. I live in Prague now, and haven’t found any meetings.

p