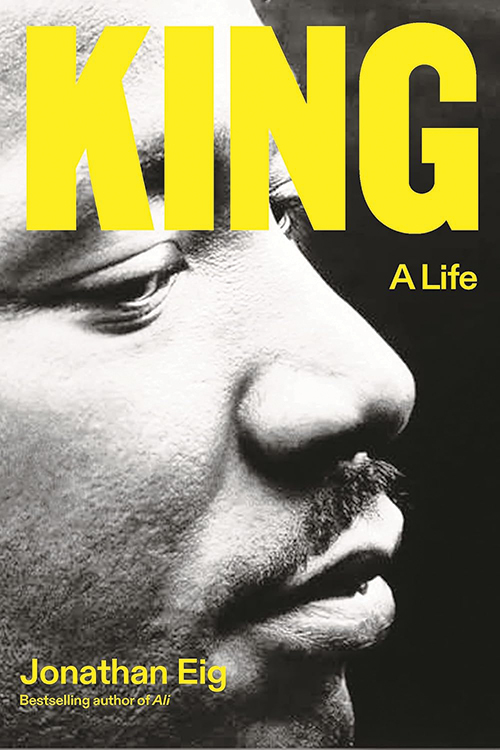

King: A Life

Reviewed by Patience A. Schenck

November 1, 2023

By Jonathan Eig. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023. 688 pages. $35/hardcover; $16.99/eBook.

This magnificent new biography of Martin Luther King Jr. takes advantage of two major sources: (1) a large number of recently declassified FBI files, allowing public access to hundreds of personal phone calls and wiretaps; and (2) there were people who knew, worked with, loved, and hated King still alive for Eig to interview. And interview them he did! He had literally hundreds of conversations with eyewitnesses to King’s remarkable life.

King grew up with considerable privilege as the son of the senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, the most prestigious African American church in Atlanta, Ga. After Morehouse College, Crozer Theological Seminary, and Boston University, where he earned a doctorate in systematic theology, he served for a while as junior pastor at Ebenezer; it was his father’s wish that he would eventually inherit senior leadership. King went his own way, but it took him a long time to outgrow feeling intimidated by his father.

When Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat in 1955, King was thrust, almost against his will, into leadership of what became the movement. He was still in his 20s, but his vision of the Beloved Community was well-formed and compelling: a calling.

We all know some of the major events in the South: the Montgomery bus boycott; dog and hose attacks on demonstrators, including children, in Birmingham, Ala.; beatings at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala.; and voter registration campaigns in Mississippi. As television broadcast these events into people’s homes, many Northerners demanded change in the South. Worried about the political ramifications of these events, President Lyndon Baines Johnson established a direct telephone relationship with King. With the president’s strong support, Congress passed major legislation: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in public housing and employment; the Voting Rights Act of 1965; and the Fair Housing Act in 1968. Johnson, however, was politically cautious. The FBI tapes reveal many conversations he had with FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

It is shocking to learn how passionately Hoover pursued King; he hated him. Tirelessly, he sought evidence that King was a communist (never found) and that he had sexual liaisons with many women (found and forwarded to his wife). As shameful as Hoover’s hounding of King was, the files are a great boon to historians.

Coretta Scott King was as committed to achieving racial justice as her husband was; in fact, their shared interest was one of the things that drew them together. An accomplished musician, Coretta often traveled to civil rights events around the country to sing. Mostly, though, she was at home with four small children. In the movement, as in the larger society, women’s ideas were often ignored.

When King turned his attention to the North, he encountered vehement racism. White Northerners might be willing to criticize the legally sanctioned segregation of the South, but many did not want their de facto segregation interfered with. At the same time, many Black people were becoming less willing to be nonviolent as the Black power movement materialized. These were times of anguish for King. He even had to be hospitalized for depression and exhaustion.

Meanwhile, he began to speak out against the war in Vietnam. This antagonized not only the president and Hoover but many of his colleagues and followers, who urged him to limit his comments to U.S. racial justice. But he continued to articulate the principle that had guided his life. He asked them to consider the perspective of a peasant in Vietnam and recognize that that peasant’s life held as much meaning and value as their own.

I confess to a couple of irritations: Eig says little about the importance of music in the movement, and, as a Quaker, I’m disappointed that he gave credit neither to American Friends Service Committee for being the first to print King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” nor to Bayard Rustin for the degree to which he educated King about nonviolence.

In the epilogue, Eig notes how little improvement there has been in the lives of people who live on streets and attend schools named for King. In those schools and elsewhere, his teachings have been trivialized. He points out that his dream is taught to every school child, but no textbooks contain his radical teachings.

What I appreciated most about Eig’s portrayal of King was that it enabled me to see King as a person, not an icon. He became unsure of himself, unable to see a way forward at times, and fearful of death. He was at times exhausted and depressed. And yet his understanding of the essential dignity and worth of every person remained solid. He never questioned that the Beloved Community could be gained, if at all, only by love and nonviolence. I finished the book with a heightened respect for him because his courage and steadfastness persisted in spite of his human imperfections. He found himself at the center of the movement, a position he had neither sought nor desired, and he gave all of himself.

Patience A. Schenck, whose life was greatly influenced by Martin Luther King Jr., is a member of Annapolis (Md.) Meeting and lives at Friends House in Sandy Spring, Md.

1 thought on “King: A Life”

Leave a Reply

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.

Thank you Patience for this moving review. It brought back a lot of memories for me. I graduated from Colgate Rochester Divinity School/

Bexley Hall/Crozer Theological Seminary in Rochester, New York. I was taught by some of the same professors who taught Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. It just so happened that I was in seminary with Dr. King’s nephew. When he graduated I had the honor of escorting Mrs. Coretta Scott King into the auditorium. But even more so than that I had the opportunity to spend twenty minutes alone with her. The President of the seminary asked me to take her into his office because she was being bombarded by television/ newspaper reporters and photographers. I spent time talking with her and offering my support of her efforts. It is a memory I will cherish for the rest of my life. Your review brings forth the humanity of Dr. King and sometimes we forget that he was just like us with all our faults. I too regret that the author did not point out the significance of the American Friends Service Committee because they contributed significantly to helping Dr. King in several ways. It was also sad to see that Bayard Rustin was left out as well. However, I am happy that the movie about his life has been released so we can put Dr. King’s efforts in a broader perspective and see the Quaker influence on his life. Well done!