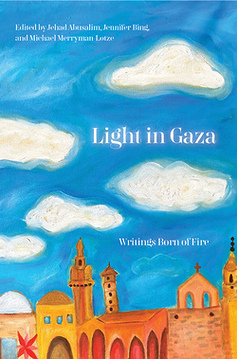

Light in Gaza: Writings Born of Fire

Reviewed by Max L. Carter

October 17, 2023

Edited by Jehad Abusalim, Jennifer Bing, and Michael Merryman-Lotze. Haymarket Books, 2022. 280 pages. $45/hardcover; $24.95/paperback; $9.99/eBook.

A plaque in a classroom at Earlham School of Religion where courses on the Bible are taught states, “Context is everything.”

In his poem “Harlem,” Langston Hughes asks, “What happens to a dream deferred? // Does it dry up / like a raisin in the sun? . . . // Maybe it just sags / like a heavy load. // Or does it explode?”

I was reminded of these quotes when I learned of the assault by Hamas on Israeli targets earlier this month and Israel’s retaliation. Quaker peacemaking asks the question, what are the seeds of war, and how may they be removed before they sprout and grow? In other words, what is the context out of which the current cycle of violence emerged?

And what might those deferred dreams be that led to the result of an explosion? Certainly for Israel it was the shattered dream of a military and intelligence operation that afforded a sense of security and safety. What was it for Gaza?

Light in Gaza is an antidote to many misconceptions about Gaza as it helps explain the context out of which the current explosion has occurred. Along the way, it describes what chef Anthony Bourdain, himself, found during the filming of his Parts Unknown cable show in Gaza in 2012: “Regular people doing everyday things . . . but robbed of their basic humanity” (paraphrased from Bourdain’s acceptance speech for an award from the Muslim Public Affairs Council).

Three American Friends Service Committee staff members who have worked on issues of Palestine and Israel for a combined total of more than 50 years have skillfully gathered and edited essays by 11 Gazans that explore far more details about life in the Strip than media sound bites provide. The purpose of the anthology is to show how Gaza is typically described through an oppressive occupier’s lens as it attempts to erase the history of the occupied. As the contributors reveal the reality of an ongoing Nakba (“Catastrophe”), they seek to break the intellectual blockade of Gaza, just as activists continue to seek an end to the physical blockade imposed on it.

I once asked an Israeli soldier about an assault on Ramallah that I witnessed, wondering why there were more than 50 armored vehicles and hundreds of soldiers for an operation to blow up one uninhabited apartment. He responded, “Everything like that is meant to be a statement.” In a chapter on growing up in Gaza through several Israeli assaults, Refaat Alareer describes how the violence and targeted killings made such statements, and what the impact was of losing more than 30 family relatives through Israeli attacks since 2001. Yet as a professor of English literature in Gaza, he taught Jewish characters in Shakespeare sympathetically.

Asmaa Abu Mezied’s chapter presents the realities of everyday life in Gaza that counter the dominant narrative, and contrasts the myth of “a land without a people for a people without a land” by describing Palestinians’ rootedness in the land and the flourishing agriculture they have practiced. Shahd Abusalama gives a history of the more than 530 Palestinian villages destroyed in Israel’s creation and describes the ongoing confiscation of Palestinian land and spread of settlements as a continuation of a settler-colonial project that Palestinians have a right to resist—as much as Ukrainians have the right to resist Russian occupation.

Salem Al Qudwa’s chapter explores the implications for structural design of buildings given constant attacks and the difficulty of getting materials. Suhail Taha shares about the creative ways Gazans deal with Israel’s control of two-thirds of the Strip’s electricity and the darkness that prevails when power is available only four hours a day. Nour Naim writes in her chapter about Israel’s use of artificial intelligence to control Palestinians and how Gazans themselves could utilize AI in their own resistance.

Mosab Abu Toha writes about the devastation of his university in the 2014 attack on Gaza, how both Israel and the Palestinian Authority ban books critical of their policies, and how Jewish author Noam Chomsky sent books to replace those destroyed in the assault. Dorgham Abusalim recounts in detail living through the “fifty-one dreadful days” of the 2014 attack, even capturing one of the Israeli strikes on his mobile phone; watching it years later, he’s overwhelmed “with the fear I felt for my life and for my family.” Yousef M. Aljamal’s chapter explores travel restrictions as “continuing Nakba” and how the “Oslo Accords, the so-called peace accords,” led to a fragmentation of Palestinian community.

In his chapter, Israa Mohammed Jamal shares personal stories of the ethnic cleansing in 1948 and his own childhood trauma from the assaults on Gaza. Basman Aldirawi presents three possible scenarios for the future: (1) no solution and a continuation of the status quo, (2) a two-state resolution that would continue to impose restrictions on Palestinians’ lives, and (3) one democratic state in which Gazans are able to live like anyone else. In light of the current response by Israel to the Hamas attack, the fear is that a “solution” will be a wholesale destruction of Gaza and trauma that will last for decades for both Gazans and Israelis. Already there is talk of how this war may push Israel finally to accept some form of a two-state solution simply to “separate” from Palestinians. Unfortunately, the option of a one-state solution now looks more remote than ever.

Gazans living like anyone else. It is what Anthony Bourdain found in 2012 that the people of Gaza could be—if not robbed of their humanity. Context is, indeed, everything. And, yes, if dreams, hopes, and aspirations are deferred, they explode.

Max L. Carter is the retired director of Friends Center at Guilford College. His book Palestine and Israel: A Personal Encounter (Barclay Press) chronicles his long association with Quaker work in the Middle East. He is a member of New Garden Meeting in Greensboro, N.C.

4 thoughts on “Light in Gaza: Writings Born of Fire”

Leave a Reply

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.

The root of the problem seems to be that after WWII, the UN (allied forces) forced Israel into Palestinian lands, apparently without paying for the lands. The backwards tradition of stealing land by force rather than mutual consent of buying land continues to cause problems like Ukraine. Another challenge is clear global definitions of what is the least-force needed, and when do military actions shift from defense to offense. Ultimately, stronger traditions of forgiveness (without being requested) amongst both Jews and Muslims would also help tremendously.

I would like to feel more sympathetic, but I’m afraid the events of the past weekend have left me shocked and cold. Do not the Quaker values of peaceful resistance apply to the Palestinians? Why do liberals always make excuses for terrorism when it is directed against Israel? Funny that you have posted no articles decrying the antisemitic demonstrations on American campuses this week and the threats made against Jewish students. The hypocrisy is hard to believe.

I commend you efforts to bring to light the life of ordinary Palestinians in Gaza. However I am both distressed and disappointed by your inaccurate presentation of the context of these events and as a Jew and a pacifist with many years of Quaker education I am particularly troubled by your biased view of “the context out of which the current cycle of violence emerged.” Does that context not also include the clearly stated aims of Hamas to kill all Jews with no distinction between civilian or soldier and their aim to annihilate the Jewish state ?Are not the centuries old history of antisemitism culminating in the Holocaust or the war initiated by Arab countries to prevent a Jewish state in 1948 also part of the context out of which this cycle of violence emerged?

Blair R

Let’s accept, for the moment, the proposition that Hamas’ stated intent of killing all Jews and dismantling the Jewish state justifies Israel’s killing of Hamas members whenever and wherever they find them. If that’s the case, then out of the 4,300+ Palestinian children who have been killed by the Israeli military’s assault on Gaza over the last month, how many should we say were likely to have been members of Hamas whose deaths are morally acceptable?

(Note that, at the moment, children represent nearly half (roughly 43 percent, to be slightly more precise) of the total Palestinian deaths; that percentage is likely to fluctuate as more civilians in Gaza die.)

Or perhaps we don’t believe ANY of the dead Palestinian children were members of Hamas, but that a certain amount of collateral damage in the killing of Hamas members is regrettable, but understandable and acceptable. I can’t imagine what that certain amount would be, but 4,300 dead children in the space of a month seems rather high, perhaps high enough to call the entire methodology of the Israeli military into question.