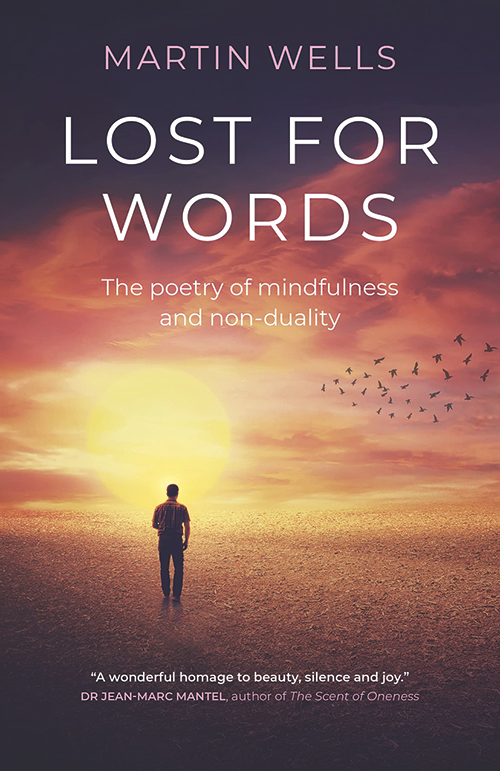

Lost for Words: The Poetry of Mindfulness and Non-Duality

Reviewed by James Foritano

June 1, 2023

By Martin Wells. Mantra Books, 2022. 104 pages. $14.95/paperback; $11.99/eBook.

According to the author, these poems just appeared daily on Martin Wells’s mental horizon during the COVID pandemic, and the author—a psychotherapist working for the National Health Service (NHS) in England and who had never before written poetry—hustled them into an open notebook. Serendipity!

I agree with Wells that they have a wit and point that explore a down-to-earth understanding of our human mental health, and he was wise to collect and publish them. Humor also abounds.

“The Caterpillar and the Psychotherapist” is a case in point. The patient, a very disturbed caterpillar, is convinced that a life change is leading him to a certain and disastrous breakdown.

Wells, having seen and guided patients through natural life changes before, is spare with words of guidance. The caterpillar complains vociferously through multiple sessions that the therapist is not doing his job. And the caterpillar feels both lost and abandoned by this neglect.

The therapist acts as he does because he doesn’t want to drown out the signals from the caterpillar’s own body and mind of a natural change foreordained by a unique evolution whose every twist and turn the caterpillar is best fitted to interpret.

Flipping through the pages, I find the title poem, “Lost for Words.” In another wise and concisely worded poem, “The Pugilist,” a poet/therapist, not at a loss for words, firmly yet gently counsels a patient whose heart and mind are still fixed in a two-fisted pose of defense in the face of a trauma now past but still lingering in echoes, potent echoes.

Rhyme comes intermittently like rain spattering the roof over this “pugilist’s” closed mind and heart, seeking to penetrate, by leaking or melting, solidly built but outmoded, unwanted defenses:

The heart so steadfastly protected,

safe but so alone.

Each beat infused with fear

and this must not be shown.

And such a yearning to be free,

to play another part,

allow another in

to the deepest regions of the heart.

In yet another poem, “The Stickiness of Ego,” Wells addresses not the patient but the ego in all of us that often divides us from our world by needless competition with our peers and/or fear of being without an anchor:

But you keep holding on—

or is it me to you?

Does fear creep into my soul

during freedom’s emptiness.

This emphasis on letting go of ego bears out the message in the subtitle for this collection: The Poetry of Mindfulness and Non-Duality. Again, Wells doesn’t beat us over the brow with the hard task of letting go of our ego or of our often-scattered attention span in a society and era that seems to nourish both.

Instead, the reader/seeker finds poems such as “The Olive Tree,” a short three-stanza poem in which an ancient olive tree speaks directly to all of us humans who have come over the years to its branches, its roots—not to mention its olives: “the same children that once climbed in me / became lovers at my feet.”

The olive tree wonders, charmingly, in the last stanza if it has ever come to our attention. And beckons: “Come, come closer.”

In this simple poem, the author—in letting the olive tree speak so compellingly—is himself now voiceless, but becomes a strong listener paying rapt attention to his own preaching in the book’s title: Lost for Words.

Martin Wells often reaches most directly to us by stepping aside and giving up his own ego but never his skills, wisdom, and compassion to help us chart a brave course—all our own—with a light of hope and inspiration leading the way.

James Foritano devours books on all subjects not only to set his course in life but to appreciate good writing and good thinking for itself. He also enjoys travel, writing poetry, and being outdoors. And he enjoys sauntering through any pleasant landscape, especially if it holds up traffic. He and his wife attend Cambridge (Mass.) Meeting.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.