Maple and Rosemary

Reviewed by Margaret Crompton with Bethan

December 1, 2023

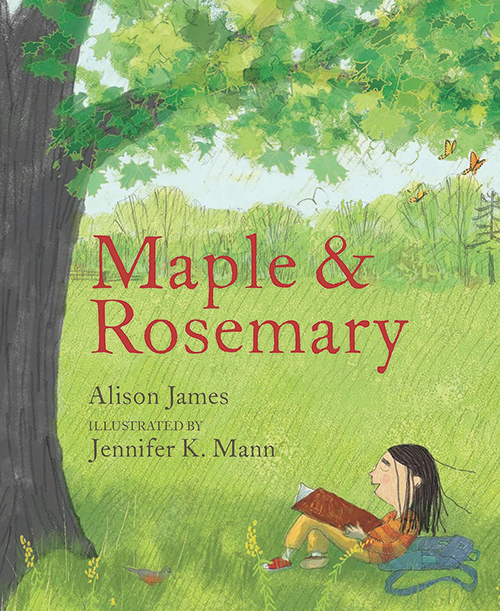

By Alison James, illustrated by Jennifer K. Mann. Neal Porter Books, 2023. 48 pages. $18.99/hardcover; $11.99/eBook. Recommended for ages 4–8.

Ten years ago, this newly built house looked onto a sloping patch of poor grass; behind was a fenced area of mud, peppered with builders’ rubble. The field beyond would produce two harvests before it too sprouted houses, including Bethan’s home. This summer, I harvested black currants from bushes intermingled with apples, and rosemary, sage, fennel, and bay. In the fall, a field maple will glow amid darker leaves of hawthorn, yew, and birch. Our yard is becoming a tiny, urban wood. No wonder I’m delighted to review this book about a tree and a child with my own young friend Bethan.

Maple and Rosemary by Alison James, a Quaker living in Vermont, tells the story of the long friendship between Rosemary, a lonely young girl, and the equally lonely tree, Maple. The clear text and vivid illustrations present Maple’s point of view: “Then one day something flew at her. It was bright and fast like a shooting star, but it had limbs, and it was raining from its eyes.” The reader is placed on a level with a robin perched on a branch of the leafy tree. The bird’s red breast and black head are echoed by an equally small figure with streaming black hair wearing a red top, as it races across the center of the adjoining page. “It” soon becomes “her”: Rosemary.

Maple’s view is represented as the reader looks down through the canopy. In one picture, Maple is in full-leaf, while Rosemary, foreshortened with a large face and minuscule feet, looks up and waves. Rosemary says, “See you.” “I’ll be here,” replies Maple. This scene is echoed later when the reader looks down through snowy, gray branches at Rosemary, now a teacher with smiling, brightly clad children, all waving and calling: “See you soon!” And Maple replies, “I’ll be here.”

Both Maple and Rosemary live through many changes. Rosemary, once the lonely, weeping child, gains confidence. She learns about such creatures as “leaf-eating caterpillars that turn into pollinating butterflies.” She catches Maple’s seeds (which Bethan calls “helicopters”) “spinning in the wind” and plants them. Next spring, “three young maples were shooting up. They were giddy and wobbled in the wind.” Maple grows old and drops a branch, which Rosemary uses as a walking stick: “As Maple grew taller, Rosemary grew smaller.” The snowy-haired woman sits on a chair reading to her leafy friend. Rosemary’s clothes are still the colors of fall.

Every word is intentional—often surprising—as in a poem. There are delicate landscapes of changing seasons: “Year after year, winter swept into summer.” These are followed by studies from bud to leaf-fall: “Leaves bloomed, burned, then fell.”

Feelings are represented with both verbal and visual impact. During Rosemary’s winter absence, Maple stands on a white field with a stark trunk and branches spattered by snowflakes. Her loneliness is intense: “Once you have a friend, you know what you are missing when they are gone. Maple wanted the winter to cover her with snow and never ever melt.” These strong images led Bethan and me to explore friendship, feelings, and loneliness.

Like Rosemary and Maple, we could teach each other. Bethan investigated intriguing aspects of art techniques and explained digital paint. She described the pictures as “realistic in a cartoon way,” which we related to an anime style. As a schoolgirl herself, Bethan suggested that Rosemary decides to become a teacher because she has enjoyed teaching Maple. With my social work background, I thought Rosemary wanted to ensure that other children would never experience her lonely unhappiness.

Bethan’s mother, Alison, works with young children. Like us, she recommends the book. I’ll give Bethan the last word: “I like best that it’s different from the tree’s point of view,” and she quotes from the jacket flap: “Together they form a bond as real as roots.”

Margaret Crompton, a member of Britain Yearly Meeting, wrote the Pendle Hill pamphlet Nurturing Children’s Spiritual Well-Being. Recent publications include poems, short stories, and plays. Bethan writes poetry. She has also contributed to the reviews of Desmond Gets Free (FJ May 2022) and Room for More (FJ May 2023).

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.