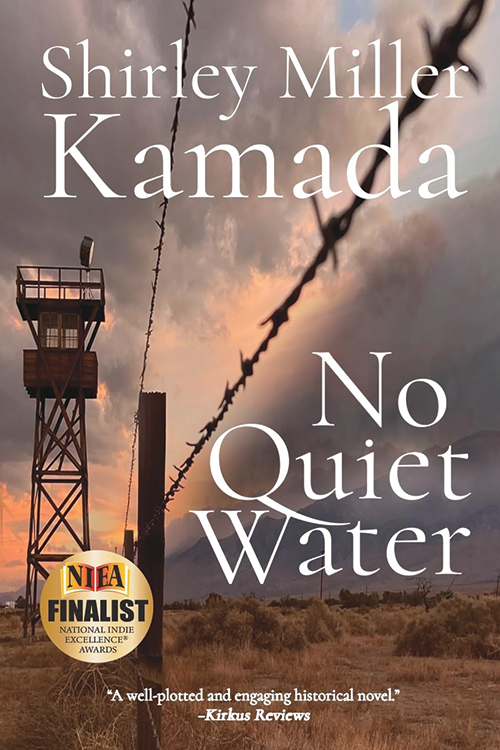

No Quiet Water

Reviewed by Judith Wright Favor

December 1, 2023

By Shirley Miller Kamada. Black Rose Writing, 2023. 356 pages. $23.95/paperback; $5.99/eBook. Recommended for ages 10 and up.

In No Quiet Water, Shirley Miller Kamada blends breathless writing with quiet lyricism in showing World War II hardships through the eyes of a Japanese American boy and his border collie, Flyer. The Miyota family grows strawberries on Bainbridge Island near Seattle, Wash. Ten-year-old Fumio and his father rise early to do farm chores, while Flyer watches nearby:

Flyer stood, muscles taut, ears erect, eyes fixed on Fumio, then headed straight for the chicken yard . . . Fumio and his father . . . [enter] the dark space between the coop and a stand of trees bordering the roadway. The pre-dawn world was quiet except for their footsteps on fallen pine needles and twigs.

While playing with his Quaker buddy and neighbor Zachary, Fumio hears a newscast announcing the attack on Pearl Harbor. Boy and dog hurry home to find Mr. Miyota sitting on the porch with his head down; when he looks up, they know “something terrible has happened.” Flyer’s report of that day uses all five senses: “The kitchen smells like dinner, but I am not hungry.” He provides physical comfort to Fumio, whose eyes become “shiny”: “I go into the living room, sit beside Fumio, push my head under his arm, and lean against his leg. He puts his hand on my head.” Flyer is a good listener: “The only noises are sighs and the beating of Fumio’s heart.” And a perceptive observer when Zachary and his parents arrive with homemade food offerings and unspoken empathy: “Zachary is on the floor beside Fumio with an arm across his shoulders like I have seen him do after a baseball game.”

Forced to leave their land and live at Camp Manzanar in Eastern California, innocent Japanese American families suffered bad food, racist indignities from armed guards, and squalid living conditions.

Fumio turned onto his side, trying to find a comfortable spot between the lumps in his cot. The straw in his mattress crackled, a stubborn stalk poked him in the shoulder. . . . Even in summer, nights were cold in the high desert.

Fumio ponders the absurdities of the politics behind war: “with the stroke of a president’s pen, people’s homes and families, entire communities, could be ripped apart.” Through letters, he and his family try to keep in touch with the outside world, and they learn of their neighbors’ advocacy efforts to oppose the unjust internment. Zachary’s father consults with a lawyer at American Friends Service Committee “to put right the bureaucratic tangle ensnaring” a friend of theirs who’s been labeled “a threat to national security.”

The trajectory of the book is unsettling, yet the story is emotionally satisfying. Quaker neighbors care for the Miyotas’ farm and for Flyer, who narrates throughout the war. The author conveys dog’s and boy’s voices with spare prose. “Fumio didn’t love Manzanar, didn’t like it, even. But he had made a few friends: Hajime, Mr. Miyatake. Even Sam wasn’t as bad as he had first thought.” Fumio looks for the positives in their terrible situation, such as forming new relationships and learning taiko drumming: “He would regret the loss of it.”

In 1943, the family is transferred to Camp Minidoka in Hunt, Idaho. Flyer’s arduous journey to Idaho, and his tender reunion with Fumio moved me to tears.

This is a terrific novel for Friends young and old. The author shines light between the lines in this moving testimony to the courtesy and grit of Japanese American citizens during one of the most grievous violations of civil rights in U.S. history. She does not name it as “a leading,” yet her decision to write this account feels to me like a leading because it demanded extensive historical research and took nearly ten years to complete. Her husband, Jimmy, was born in an Idaho internment camp, and readers get a bit of his perspective in the afterword, where she also honors his parents, Isao and Yuriko Kamada.

This is the author’s first novel. I hope she writes another. I’ll be first in line to buy a copy. More information is available on the author’s website at shirleymillerkamada.com.

Judith Wright Favor belongs to Claremont Meeting in Southern California. She attended Richmond Elementary School in Portland, Ore., during the 1940s. It is a bilingual school where classes are now taught in Japanese and English.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.