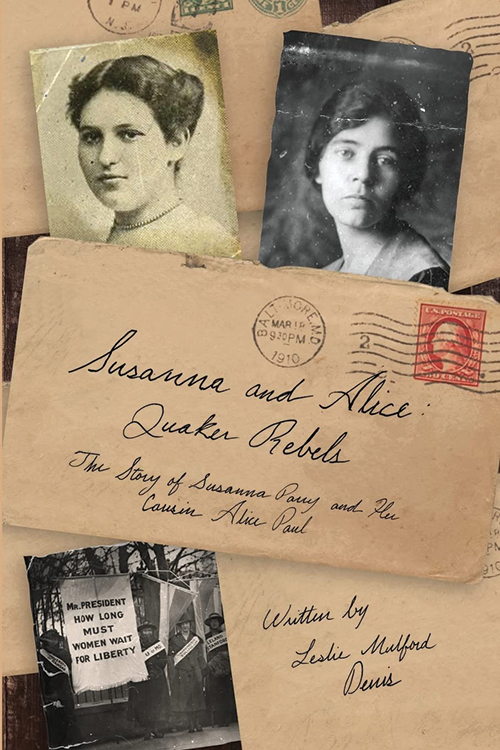

Susanna and Alice, Quaker Rebels: The Story of Susanna Parry and Her Cousin Alice Paul

Reviewed by Claire Salkowski

August 1, 2023

By Leslie Mulford Denis. Oxford Southern, 2022. 272 pages. $19.95/paperback; $9.99/eBook.

In our twenty-first-century world, it is hard to imagine life over 100 years ago during the Progressive Era, but that is the world we enter in this detailed volume about the life of two Quaker cousins: one who sacrificed dearly and had an enduring impact on women everywhere, and one who lived a quiet life, hemmed in by dictates of her conservative Quaker family in Riverton, N.J.

The story follows these revolutionary yet privileged “New Women” of the twentieth century, Alice Paul and Susanna Parry, cousins who were undoubtedly fond of each other and came of age at the turn of the century. Through the experiences of their early days at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, extensive European travels, work in the settlement houses in New York and England, and their subsequent education at the Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre in England, we see them embark on very different paths that continued throughout the remainder of their lives.

The story of these two cousins is told by the author, a descendant, through letters she inherited from her own contemporary cousin. The tattered box of forgotten letters was discovered in the recesses of the attic that had once been the family home of the spinster Parry sisters, Susanna and Beulah. Through the echo of a time long ago, the story of Susanna and her family, along with the exploits of her infamous cousin Alice, are revealed in the writings penned—many by Susanna herself—beginning in the early 1900s when both cousins began their college careers. The author describes in illuminating detail the life and history of that time while weaving in the story of Susanna’s and Alice’s life journeys, which overlap through their family ties but whose trajectories take off in very different directions.

While Alice found her calling as a radical suffragette who challenged the politics and politicians of the day, changing the world, Susanna quietly rebelled but was ultimately thwarted in a forbidden love for the college roommate she endearingly called “Wifie.” Brokenhearted, Susanna struggled through depression and later tuberculosis but ultimately found a way to carve out a life that included untold generosity and dedication to family and friends while remaining true to herself.

As a Quaker woman who came of age during the feminist days of Betty Friedan, I was humbled and awed as I learned about the concentrated study, hard-won victories, and personal suffering of the generations before me, and the single-minded dedication of Alice Paul who spent her entire life fighting for the freedoms and rights we women enjoy today. It was due to the courage and resolve of Alice Paul and her fellow suffragists, the “Silent Sentinels,” who picketed Woodrow Wilson’s White House and the Capitol, endured the rage of opposing crowds, and were jailed in atrocious prison conditions, that the Nineteenth Amendment was finally passed in June 1919 and ratified in August 1920. Thus women in this country were allowed to vote for the first time in the elections of 1920. Alice continued her fight throughout the rest of her long life, and although she authored the Equal Rights Amendment for Women and saw it passed by Congress in 1972, she never lived to see it ratified and subsequently defeated by its opponents when ratification failed by three states.

The story of these two Quaker cousins offers a rare glimpse into the history of a bygone age that produced some of the most important discoveries and hard-won rights that we blithely take for granted in present times. Through the lens of these two women’s lives, we have a chance to look back, learn, and remember how far we have come and recognize how far we still have to go.

Claire Salkowski is a member of Stony Run Meeting in Baltimore, Md., where she has been active and also attends the Northern Neck Worship Group from her creek home in Heathsville, Va. As an educator, administrator, mediator, and restorative circle practitioner, she worked both nationally and internationally and is currently semi-retired.

6 thoughts on “Susanna and Alice, Quaker Rebels: The Story of Susanna Parry and Her Cousin Alice Paul”

Leave a Reply

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.

I love the read so far! Ordered it as soon as I could! It is powerful to hear about how we got things done over 1oo and fifty years ago and we are still doing it! I thank you for this strong, affirming account of everyone being apart of the history that helped us see we are all a part of our history! It helps me hear about complex women in the world that were so much apart of getting us to where we are now and if we aren’t careful we could loss it all because of men of power or the men in Power!

To read about someone like me that grew up hearing I was less then because I was a women and also gay was upsetting while growing up and now hard to watch us on the verge of losing it all after we worked so hard to get equal rights? I am struggling with where I belong in the world at 62 and a friend sent me this link and I ordered your book as soon as I could! I started reading it and couldn’t stop but I like a physical book when I read something I know I am going to reread over and over again because I struggle with reading because of MS and double vision! Thanks you for this account of women history! I have 2 photos of the women protesting in front of the Whitehouse! I am happy to read their history in your book! Thanks again for bringing this to the for front!

Thank you so much for your kind comments, Debbie. I was called to write this book when I discovered in the letters that Susanna was not allowed to live her authentic life, or even talk about it openly. It broke my heart open to think of the countless women (and men) who have been silenced for the sake of so-called propriety. Susanna and Alice were, as New Women, different from traditional women. Brava to them, and all women, who dare to be different. Alice was iconic and at times very isolated in her struggle for equality. Susanna was at times very alone in her struggle for freedom of choice. It is not easy to be different. But difference is at the heart of beauty. Carry on.

And right you are that we should take care not to lose the rights so many fought so hard to obtain. Use your voice: demand equality and freedom of choice, and vote.

Again, thank you for your appreciation of the book about these inspiring women. I gave 8 years of my life to the writing of it, and if it has helped and encouraged you, it was well worth the effort.

I was so excited to see this article and find out about this book. That is, until I read a little farther and encountered the name “suffragette” and cringed. Anyone who has read and researched the history of women in the U.S. knows that they called themselves Suffragists, “ist” not “ette.” The “ette” came into being only as a joke against them from some newspapers. I can’t help but think that these fine, heroic women roll over in their graves every time some well-meaning person calls them ‘ettes” by mistake.

I, too, had a cringe reaction. My understanding is that the term suffragette was applied to British suffragists as a derogatory term and was adopted by some. It was not really used in America. So the term is ill applied to American women who worked for the vote.

See this from the National Park Service (NPS.gov):

Although we often see suffragist and suffragette used as though they mean the same thing, their historical meanings are quite different.

The terms suffrage and enfranchisement mean having the right to vote. Suffragists are people who advocate for enfranchisement. After African American men got the vote in 1870 with the passage of the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, “suffrage” referred primarily to women’s suffrage (though there were many other groups who did not have access to the ballot).

The battle for woman’s suffrage was in full force in both Britain and the United States in the early 1900s. Reporters took sides, and in 1906, a British reporter used the word “suffragette” to mock those fighting for women’s right to vote. The suffix “-ette” is used to refer to something small or diminutive, and the reporter used it to minimize the work of British suffragists.

Some women in Britain embraced the term suffragette, a way of reclaiming it from its original derogatory use. In the United States, however, the term suffragette was seen as an offensive term and not embraced by the suffrage movement. Instead, it was wielded by anti-suffragists in their fight to deny women in America the right to vote.

Please allow me to correct your misunderstanding, Ann Marie.

In her comprehensive review, Claire Salkowski rightfully calls Alice both a Suffragette and a suffragist, because she indeed was both. She was a Suffragette in England and a suffragist in the States. My book clearly distinguishes between the two. Alice even called herself a Suffragette when she trained in England as a member of the Pankhursts’ Women’s Social and Political Union: she “came clean to her mother about her involvement with the WSPU in a January 1909 letter: ‘I have joined the Suffragettes — the militant party…the ones who have really brought their question to the fore (amid) much comment and criticism.'” (page 120-21) When they left England and the WSPU to work for suffrage in the States, Alice and Lucy Burns “agreed that their tactics in the States would be less militant than those of the WSPU in England. Completely non-violent, they would be suffragists, not suffragettes.” (page 127)

To learn more about Alice’s dedication to suffrage in England and America, I encourage you to read my book. I worked hard to get my facts straight and present an accurate and detailed account of the Suffragettes in England and the suffragists in the States. I am certain no women have rolled over in their graves about it.

In her comprehensive review, Claire Salkowski rightfully calls Alice both a Suffragette and a suffragist, because she indeed was both, a Suffragette in England and a suffragists in the States. My book make this distinction clear. When she was a member of the Pankhursts’ Women’s Social and Political Union in England, Alice considered herself a Suffragette “and came clean to her mother about her involvement with the WSPU in a January 1909 letter: ‘I have joined the Suffragettes — the militant party…the ones who have really brought their question to the fore (amid) much comment and criticism.'” (page 120-21) When Alice and Lucy Burns left England and the WSPU to work for suffrage in the States, they “agreed that their tactics in the States would be less militant than those of the WSPU in England. Completely non-violent, they would be suffragists, not suffragettes.'” (page 127)

The book never refers to the brave women working for the vote in America as suffragettes. They were suffragists.