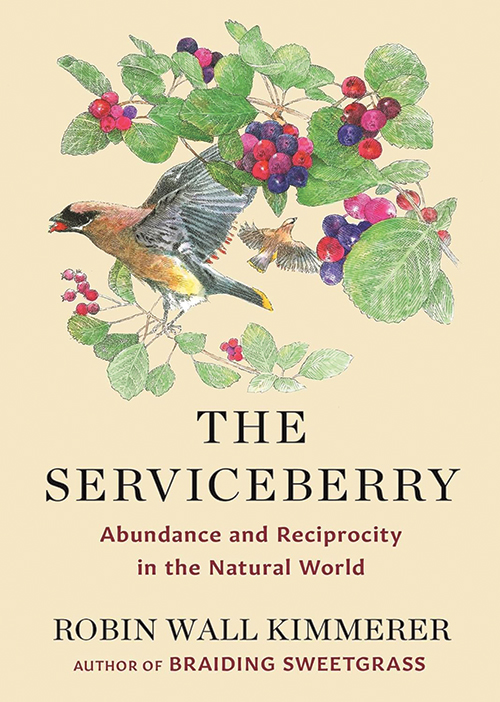

The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World

Reviewed by Ruah Swennerfelt

February 1, 2025

By Robin Wall Kimmerer. Scribner, 2024. 128 pages. $20/hardcover; $10.99/eBook.

This long-awaited third book from Robin Wall Kimmerer is a delight for all who appreciate learning about ecology and economy through the eyes and heart of an Indigenous person. Kimmerer, a botanist and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, is known to and appreciated by the many people who cherished her 2013 bestselling book, Braiding Sweetgrass. The Serviceberry is a hopeful book, an ecology book, an economy book, and a spiritual book. Instead of chapter headers, about a dozen lovely line drawings, by artist John Burgoyne, act as natural section breaks: a bee pollinating a flower, rain falling softly on plants, a little free library packed with books.

While gathering Serviceberries from the side of the road, Kimmerer wonders, can we learn from Indigenous wisdom and the plant world to reconsider what we value most? She explores how the economy of the natural world is one of abundance and reciprocity, and the Serviceberry tree, beloved for its fruits, for medicinal use, and for the early flowers as a first sign of spring, provides a good example. The tree produces loads of berries that will be eaten by birds, insects, humans, and other mammals. This is the tree’s gift of abundance. The birds spread the seeds after eating the berries, helping with the propagation of the trees. This is reciprocity in action.

Kimmerer imagines a system where resources circulate through communities, creating webs of interdependence that nourish both humans and nature. She provides many examples in contrast to the growth economy in which we dwell. She writes, “Eating with the seasons is a way of honoring abundance, by going to meet it when and where it arrives. A world of produce warehouses and grocery stores enables the practice of having what you want when you want it.”

Kimmerer explains how our economic food system creates scarcity rather than abundance and promotes accumulation rather than sharing. She explores how a gift economy works. The berry giver, the tree, and the receiver do not pass money for the exchange. It’s not hard to find gift economy examples in our lives. Potluck meals, clothing swaps, food pantries, and bartering are just a few. My relationship with the tree includes picking the berries and sharing them with others in pies and juices. If I buy the berries in the market economy, the relationship ends with the exchange of money, even though I may make the pie to share. But the relationship to the tree is broken. When we view the berries (or trees, water, or other items) as a commodity, there can be exploitation. She asks, how did we come to this broken relationship?

Throughout the book, Kimmerer considers how the commodity money economy has hurt people, financially and emotionally. To illustrate another way, she shares the story of a farming couple who invited neighbors to come and pick Serviceberries for free. When asked why, the farmer told Kimmerer that the offer creates relationships with their neighbors that might encourage them to come back to buy their pumpkins, apples, and other produce. The desire for relationships was the main objective; the resulting sales were secondary.

She points out that the Indigenous understanding of the gift economy has no tolerance for creating artificial scarcity through hoarding. If we shop only in the large supermarkets, we no longer support the small farmer financially and miss out on the rewarding relationships that were possible. Kimmerer recognizes that we have the ability to create our lives in imitation of the close-knit communities of old. And through the structures of the gift economy, we can extract ourselves from the cannibal economy that surrounds us. She writes convincingly:

I cherish the notion of the gift economy, that we might back away from the grinding system, which reduces everything to a commodity and leaves most of us bereft of what we really want: a sense of belonging and relationship and purpose and beauty, which can never be commoditized.

This little book (just over 100 pages) is like a beautiful poem filled with love, and it teaches us about an economy built on respect and relationship. It’s funny that Kimmerer says she doesn’t understand a lot about economics, but what she’s created in The Serviceberry is the best economics lesson I’ve encountered.

Ruah Swennerfelt is a member of Middlebury (Vt.) Meeting and is clerk of the New England Yearly Meeting Earthcare Ministry Committee. She also serves on the Third Act Faith Coordinating Committee and is a co-coordinator of Sustainable Charlotte Vermont. She and her husband are homesteaders on lands that once were home to the Abenakis.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.