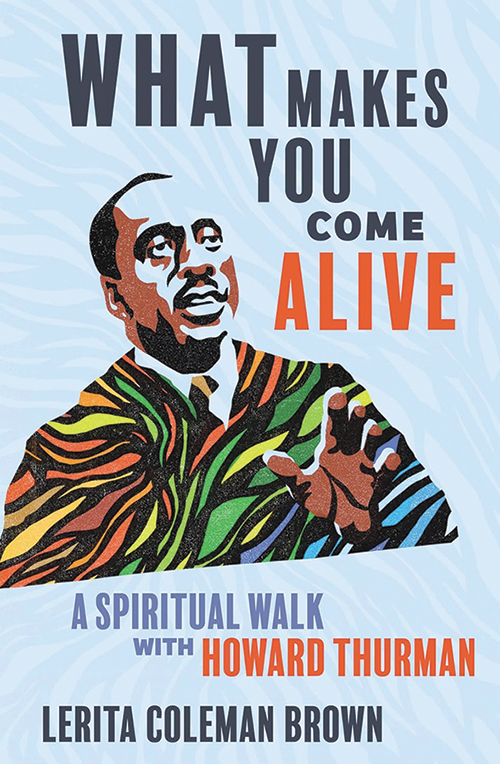

What Makes You Come Alive: A Spiritual Walk with Howard Thurman

Reviewed by Ron Hogan

October 1, 2023

By Lerita Coleman Brown. Broadleaf Books, 2023. 213 pages. $26.99/hardcover; $24.99/eBook.

Lerita Coleman Brown identifies deeply with the Black American theologian and mystic Howard Thurman. It goes back to when she read his 1949 book, Jesus and the Disinherited. It was a “game changer” of a spiritual text that offered her “a deeper understanding of Jesus’s liberating and transformative spirituality” and a “roadmap to a place of psychological and spiritual freedom for everyone.” As her appreciation of his writing grew, Brown self-selected Thurman as a spiritual mentor: “I stopped feeling strange for seeking silence, stillness, and solitude,” she writes. The connection she feels to his thought is always personal: “When I read about Thurman’s experiences in nature, my heart leaped,” she reflects in another chapter. “I had not been the only Black child to uncover God outdoors!”

In What Makes You Come Alive, Brown seeks to distill the essence of Thurman’s spiritual philosophy for a contemporary audience, and it’s a solid effort. Friends will take particular interest in her recurring emphasis on the semester Thurman spent at Haverford College in 1929, studying under the eminent Quaker mystic Rufus Jones. Although Thurman’s cultivation of a silent communion with the Divine began as a youth in Florida, well before his encounter with Quakerism, it was the time with Jones that firmly grounded his mystical pursuits. (That said, Thurman did not idolize Jones blindly, taking note of his indifference to any approaches to mysticism not grounded in Christianity and his apparent lack of concern for racial injustice in the United States.)

Though Thurman was formally positioned within mainstream Protestantism, as a Baptist minister and then later as the co-pastor of the interdenominational Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, the Quaker principle that continuing revelation is available to anyone willing to open themselves up to God was a cornerstone of his faith. Brown has a lot to say about the possibility of such encounters, and the way they can cut through the “ceaseless chatter” and “unrelenting distractions” of the modern world, if we’re able to quiet ourselves enough to notice Spirit’s presence and influence.

She leans particularly hard into the notion of divine influence, to a point where the spiritual begins to roll over into the magical. In the opening pages, Brown recounts how she went to a religious festival and mentioned to another attendee that she was there to speak about Thurman. That woman promptly dashes off, and then returns, offering Brown a portrait of Thurman that she herself had painted. For Brown, this is just one example of potential “sacred synchronicities” that suggest the possibility of ongoing divine intervention in our lives, on a par with the kind stranger who stepped in to pay an unexpected luggage fee that nearly prevented an adolescent Thurman from boarding the train that would take him to high school.

It’s a fuzzy line, to be sure. When Thurman knew that he wanted to meet Rufus Jones and study with him, was it really a “holy coincidence” that he accepted a speaking gig in Philadelphia, Pa., and met somebody who knew Jones and could speak to him on Thurman’s behalf, or was it just a case of Thurman creating opportunities for himself? In some ways, it really does boil down to what you believe. If you subscribe to the notion of pronoia, “the feeling that a force or divine presence is conspiring to help us,” you’re not just likely to interpret fortuitous circumstances as examples of Spirit’s subtle guidance in your affairs; you may find such incidents building upon themselves, to accumulative effect.

For Thurman, of course, this wasn’t just magical thinking. Though he drew on many influences, his vision of Spirit was firmly rooted in his Christian heritage and his belief that, in Brown’s phrasing, “the true message of Jesus centers on love, intrinsic worthiness, prayer, and the worship of the living God.” This vision, particularly its commitment to nonviolence, was a significant influence on Martin Luther King Jr. and other members of the Civil Rights Movement, and Brown firmly believes it has much to offer modern activists as well. Her vision of activism is expansive, encompassing “anything that helps to heal people and the world.”

It’s exactly the sort of inclusive approach one might expect from a book with a chapter subtitle encouraging readers to “recognize everyone as a holy child of God,” another notion most Quaker readers will find comfortably familiar. And it’s entirely in line with Brown’s overall take on Thurman, positioning him as someone who spoke to real-world conditions by emphasizing their divine underpinnings. Seeing how deeply she takes that message to heart, it’s no wonder how enthusiastically she claims Thurman as “my spiritual guide and companion,” finding joy “as his life and words lead me to the Light, to the Wholeness he knew.”

Ron Hogan is the audience development specialist at Friends Publishing Corporation and the author of Our Endless and Proper Work: Starting (and Sticking to) Your Writing Practice (Belt Publishing, 2021). He is a member of Flushing Meeting in Queens, N.Y.

2 thoughts on “What Makes You Come Alive: A Spiritual Walk with Howard Thurman”

Leave a Reply

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.

Hogan’s review of What Makes You Come Alive: A Spiritual Walk with Howard Thurman, by L. C. Brown, is an invitation to enter into Thurman’s religious experience. The next step to take in spiritual transformation is to become a servant-leader encouraging the other. Based on Joh 13:4, 5, I wrote in After the Fire A Still Small Voice, in the style of lectio divino, “Enabling the other to shine/ equipping recognition, identifying/ spiritual generosity, linking one to the other,/ especially forgiveness diminished nothing,/ confirmed, even uplifted common achievement/ to the apex of appreciative thankfulness.” This is what Jesus did. this is what Thurman did. Thank you for an excellent review.

The title alone is inspiring.