Am I a “young Quaker”? What does it mean to be one of these, and what’s the relationship between being “young” or “relatively new” to Quaker participation? When I participated in a mentoring program in New York Yearly Meeting almost two years ago, I was a “seeker,” and my partner in the program was a “mentor.” In a practical and helpful description, the program’s organizers loosely defined these terms as young adult Friends (YAFs) and “experienced” Friends respectively (even they placed this adjective in quotation marks). While walking in long circles around the park on phone calls with my fantastic mentor, attending workshops together, procuring coffees, and meeting up at delicious spots, we shared our mutual confusion with the terms. She relayed her confusion about what specifically made her a mentor in the relationship, and thought about the ways she approached the program as a seeker: learning from the experience of the program and learning from a new friend.

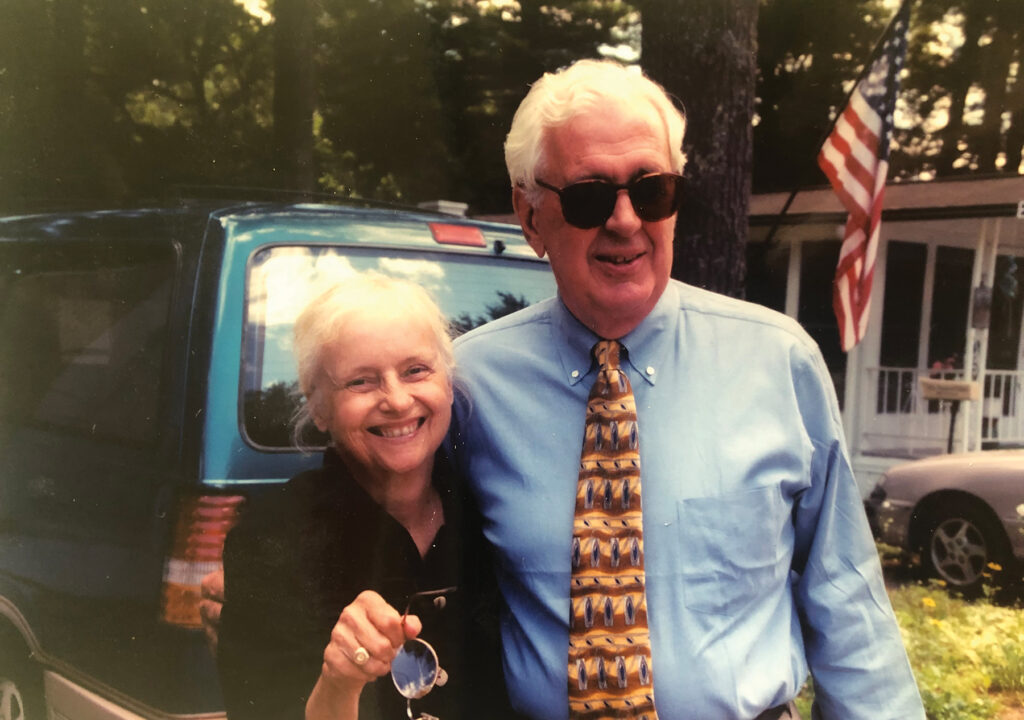

Another way I’ve come to understand what it is to be a young Quaker is not from who I am now but who I was in those days of long ago: that is to say, when my grandparents were my “grandparents” and I was a young “child.” During that time, my grandparents brought me to a strange, brick building with wood floors and cloudy glass-paneled windows. There they’d say hello to their friends and have coffee but only after an infinite span of unresponsive motionlessness. I remember that my grandparents Jan and Harry sat on either side of me, and I can recall the warmth of their arms, the weight of their silence, and my grandmother rummaging in her bag for a folded piece of notepaper and a pen. I’d slowly unwrinkle the notepaper and pass time by doodling. I’d come to know this place as “meeting” and that their friends were, in fact, their friends, but also Friends.

As I grew up, I felt that my grandparents’ friends and the Friends of this meeting were my friends too, and the lessons I learned there began to shape my values, ones that I still hold closely to now. They attended a meeting in a town called Crosswicks. It is surrounded by central New Jersey farm fields and has houses sprinkled around three roads that cross and merge, running alongside the Crosswicks Creek, which slithers out toward the Delaware River. As of the 2020 census, Crosswicks hosts a population of around 850 people. In Crosswicks’s center, the roads intersect in such a way to surround an open, square field of grass. Bordering this area, there’s the town library; a post office; a community center; a small Methodist church; and further down the street, a firehouse whose duties have recently been incorporated by neighboring Bordentown.

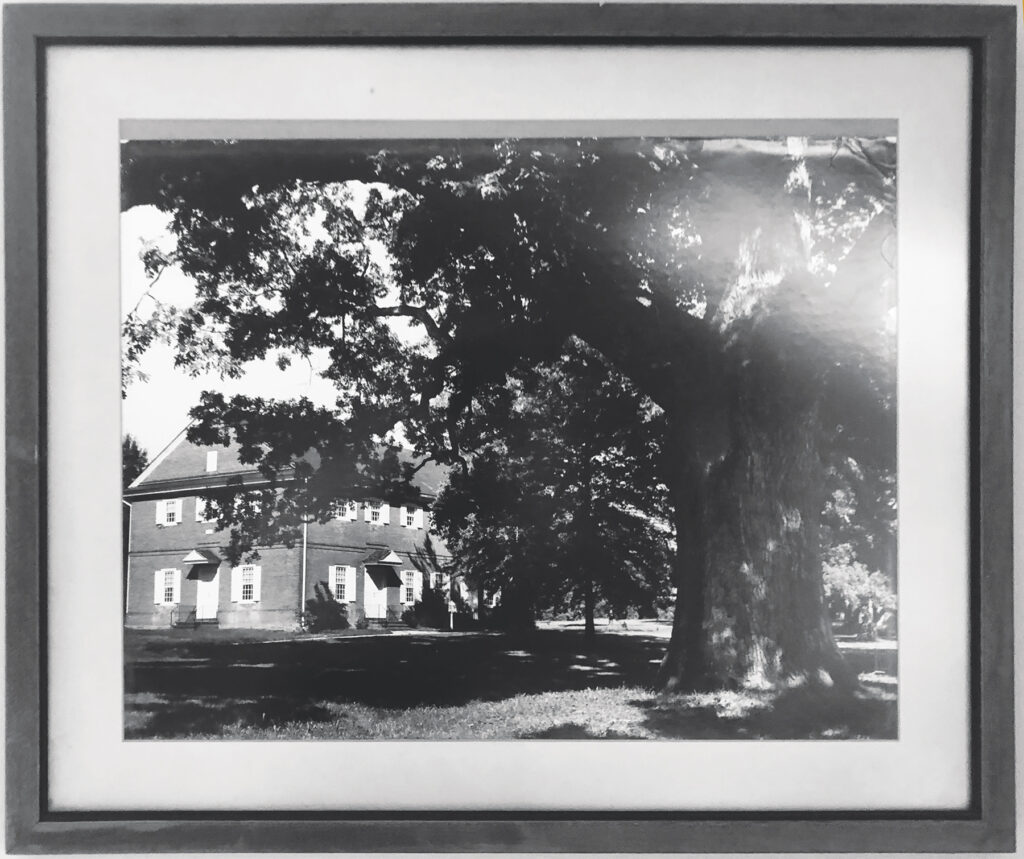

However, in the very center of the field is a statuesque building, textured with an orange-red brick exterior, symmetrical paned windows with white shutters, and stately trees punctuating the bright lawn: this is the Crosswicks Meetinghouse. The first minutes of the meeting date back to 1684. The brick building that stands today replaced the original wood meetinghouse, and it opened amidst the backdrop of the Revolutionary War. In fact, during the war, as British forces moved from Philadelphia to Jersey, a skirmish occurred in Crosswicks, and a cannonball crashed into the bricks of the meetinghouse’s second floor. A black rupture in the facade is still visible today.

Perhaps the centrality of the meeting’s presence in this town of Crosswicks, the mythos of its bricks reaching back into the centuries, the cannonballs and soldiers (who during the Revolutionary War encamped in the meeting with the understanding that they were to vacate on Sundays while services were held), the figures of the past it held, and my childhood visits in this space all contributed to reach deep and hold my imagination.

I liked the weight of the history: how over the hour of worship, it conjured a sense of community and imagination of others’ lives—the sense of not only the immediate presence of others sitting on the meeting’s benches on a given day but the intangible presence of those who had sat there before.

An edition of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s Faith and Practice, published in 1955, once was stationed at my grandmother’s desk but has since been inscribed to me and lives on my bookshelf in Brooklyn, New York, where I’ve lived since 2021. Under a section titled “Queries Addressed to Members on Worship and Ministry,” a question is put forward:

Remembering the peculiar tenderness . . . for the children, do you exercise a loving and watchful care over the young people of your Meeting? What ways do you find helpful in awakening religious experience among your children?

In the next section, the book advises that the first of the main responsibilities for overseers, a position of dedication to taking a personal interest in the welfare of each member of a meeting, is the care of young people. To do so, it counsels:

Overseers should foster influences which tend to promote the religious life of the children and young people of the Meeting, whether members or non-members, and should give them an understanding of the principles and practices of Friends. . . . Young people often desire to be used in the life of the Meeting. Older Friends should recognize this fact and do what they can to satisfy this desire.

I find this guidance to be true to the experience I had of those who were older reaching out to and welcoming me. The book’s blue hardcover is cracked at the corners, the pages brittle, but this gift itself is evidence of this exercise of care from older folks imparting, passing on, and conveying the ideas they’ve come to understand.

Harry’s wall.

As a child, I felt something powerful about the silent stories that seemed to charge the air during Sunday mornings, a shared vigor that circled from one person to another to the spirit of the whole. A sense of concentrated cognition was perceptible and instilled this very desire “to be used in the life of the Meeting.” I wanted to find out more about the weighty presence I noticed the adults moved with, the integrity they held in their communication. I observed my grandmother serve as the clerk of the meeting for years, and I wanted to emulate the mischievous, captivating, joyful spirit of leadership with which she addressed the meeting. I wanted to be friends with her fellow Friends; share updates; and answer questions on school, dance, activities, and plans. My relationship with Quakerism sprang from my family’s history, and my continuing participation in it was set in motion by the interest, care, and guidance given to me by those who were older.

From life as a young, young Quaker to what I suppose now is a “young Quaker,” changes have happened. I’ve moved out of childhood, experienced my first home that I live in alone, graduated from college, started a career: all activities difficult for me to visualize coming to fruition when I was that young, young Quaker. Some things are the same. I still feel so close to who I was when I sat in Crosswicks Meeting, searching: sometimes restless; sometimes creative; sometimes calm, open, and appreciative of being cared for. I still tend to pass an hour of worship by listening to sounds and looking at the patterns of light hitting the floor. Other things are different. I no longer consider a Sunday meeting as a feat of endurance but as a welcome pause from a stressful week and page-long to-do lists. These days, trying out post-school life in one Queens and two Brooklyn neighborhoods, it’s been a while since I’ve been back to the meetinghouse in Crosswicks. A meeting in New York City brings different sounds to pay attention to: sirens and conversations and clanking through an open window. My grandparents are still alive in my mind and spirit but no longer next to me at meeting, sharing the warmth of their arms as we sit in rich stillness together.

How can we think about young without relation to old? In addressing questions around the engagement of young people (such as how to foster a sense of spirituality in them), it’s important not to focus on the young exclusively. Instead, remember that it’s the relationships and dialogue between all members of the meeting that allow for the life of the meeting to be rich with ages, experience, and shared time. It’s the relationship to the past, the shared ideas, and the spirit of the community that naturally enable the engagement of new and interested people. Feeling welcomed and cared for by those who have insights and the experience is more than enough to shine some light for anyone who is seeking something.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.