A Vocational Discernment Project for Young Adult Friends

Quaker practice has many beautiful pieces of wisdom to offer young adults, and one way to share them is to create opportunities to experience that wisdom. Since 2020, we have been working on a vocational discernment program designed to do just that.

The young adults we have worked with have been hungry for specific support for learning to make strong decisions about their future: decisions that they feel good about. Each person is navigating their own path, which is filled with unexpected challenges, twists and turns, ways opening, and doors closed. In a world where we have access to an unprecedented number of strengths’ assessments, occupational tests, and advice on what we all should be doing, parsing through information and making sense of our next steps is tricky.

As millennials, we know this well. We are the generation of the side hustle; the spiritual “nones” (on surveys, those who mark “none” under religious affiliation); nearly insurmountable student loan debt; and the long-term, full-time unpaid internship.

The most magical moments in our workshop, the ones that have felt that we were clearly doing ministry, have come through conversations we have had with participants who had brought their full and complicated selves. We have had one-on-one meetings with participants who came up to us after seeking support and counsel. We watched as participants supported each other in new ways that emerged when they realized they could holding space for each other outside of our workshop! This type of connection made possible through Quaker practices is beautiful.

One way Quakerism can engage young adults is by sharing our tools, practices, and principles within the context of their seeking some goal. Our curriculum offers a pathway for this.

Left: Workshop at Friends Camp, June 2022. Right: Workshop at Beacon Hill Friends House, October 2022.

A Movement of Spirit: How the Project Came Into Being

We met in 2018 as young adult Quaker ministers. Jen had just finished a degree at Vanderbilt Divinity School, and Greg had just moved into a full-time ministry role. Over about two years, we supported each other through career and ministry discernment: learning more about each other, asking each other hard questions, and even commiserating about shared challenges.

At its core, our vocational discernment project comes out of what has been fruitful for us: community; learning, time and again, to trust our inner wisdom; and listening to that wisdom through noisy inner critics.

In January 2020, Jen took a new job as the program manager at Beacon Hill Friends House (BHFH), a Quaker center and 20-person intentional community (many of whom are young adults and not Quakers). Jen surveyed residents about what kind of Quaker programming they might be interested in, and the results were overwhelming: people wanted to know what Quakers had to offer about navigating work and careers.

So Jen brought this question to Greg because of the friendship we share and because she knew Greg had held a concern for campus ministry for a decade. At the same time, Greg had been wondering what introduction to Quaker practices and principles Quakerism had to offer college students. That December, we held a pilot workshop for house residents, which became the foundation for a BHFH-led initiative, which had additional financial support from the Forum for Theological Exploration (FTE) and the Lyman Fund. It was called the “Living Your Call: Vocational Discernment Program.”

With the help of young adult Quaker artist Joey Hartmann-Dow, we also crafted a 40-plus-page workbook to use as both part of our program and also functioned as a self-guided book for journaling and reflecting, which could be turned to throughout life.

As we look back now almost three years later, we can see the ways that Spirit was working through us and our experience as young adults to respond to a need in the world.

And way opened. At the time of this writing, we have led this workshop 23 times and had over 200 participants throughout the United States in Quaker institutions, including Earlham College; Guilford College; George Fox University; Haverford College; West Hills Friends Church in Portland, Oregon; First Friends Meeting in Greensboro, North Carolina; Quaker Experiential Service & Training (QuEST); Friends Camp; New England Yearly Meeting Young Adult Friends; Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Young Adult Friends; and for Friends Committee on National Legislation program assistants. We have also led presentations on our program for the Friends Association of Higher Education and the Quaker Religious Education Collaborative.

We have additionally run these workshops in non-Quaker contexts, including at Lewis and Clark College in Oregon and Lyndale United Church of Christ (Minneapolis, Minn.). Often, the setting was another religious congregation (or an interdenominational group) that wanted to share other Christian spiritual practices with its congregants, and they were curious about Quakerism and what it might open up for people.

Left: Workshop with Philadelphia YM Young Adult Friends, May 2023. Right: Workshop at George Fox University, February 2023.

A Framework Rooted in Quaker Practice, Widely Accessible

Why has this curriculum had an impact on such a wide audience, particularly young adults? We believe it comes down to three things: First, the language we use is accessible, focused on a subject meaningful to the participants’ daily lives. It is intentionally open to multiple perspectives and beliefs and can make room for folks to hear their own inner wisdom. Second, putting Quaker ideas quickly into practice gives people a chance to experience the Divine stirring within them. And third, we invested in making something beautiful.

When we began our vocational discernment project, we decided to begin with a funny icebreaker: We asked folks how they would have answered this question when they were a small child: What do you want to be when you grow up? The answers have ranged from quite normal (teacher, firefighter, parent) to dreaming big (astronaut, first woman president of the United States) to something only a child could think up (a fire truck).

We do this at the beginning to speak to a larger point: From the time we are small, the world around us lets us know that we need to have an answer to that question. In part, that’s one of life’s great questions. As we get older, we are asked this question over and over in different ways, especially at key points in our lives, such as graduating from educational programs or switching jobs. Furthermore, the job we have now might not be a core part of our identity as adults, even if it is a large part of our lives.

So how should people balance having a purpose in life with the facts of our lives? We don’t pretend to know the answer to that question for each participant. Instead, we lead by being unabashedly human. We share our own stories, not as advice to be like us but to demonstrate vulnerability as a way to help others to share their stories. We are honest and hold space for young adult participants to name the reality of their lives and to be held and heard. We don’t use jargon, and when we do use a term that folks might not know, we explain it. We sometimes offer contrasting perspectives! We also encourage folks to translate what we say into words that meet their own worldview: So if we talk about God or Spirit, we invite young adults to hear it in their own personally significant religious language.

We define “vocation” (a term that comes from the Latin vocare, meaning “to call”) in a broad way: that to which you are called. This vocational resource is far from discerning whether one may be suited to a career as a spiritual director, an accountant, or a bakery owner. Instead, it provides young adults with a spiritually grounded toolbox that can serve them in discerning their calling in life as they and as their lives change. We aren’t called to any one specific thing for the duration of our lifetimes, and our vocational discernment aims to meet that reality.

All of these pieces—keeping the language accessible, focusing on a subject rather than specific beliefs, and creating space for multiple beliefs and perspectives—contribute to a meaningful experience for young adult participants.

So how is this curriculum Quaker-rooted? And how do we use Quaker practices? A distinctly Quaker approach to anything is particularly hard to define. Quakerism, in its founding principles and values, is a religious approach that is decentralized, non-creedal, and focused on the interior experience of God/Light/Spirit, however you may name that which is bigger than yourself. The diverse audience of Friends Journal likely knows this well.

For us, Quakerism at its core holds that every person has that of God in them, and every person has unique gifts and skills that can make something manifest in the world. It’s our practice to sink down and listen for our inner wisdom to guide each of us, and one of the best ways to do that is in community with others. We can support each other by helping ourselves to go deeper in listening to our own guide.

The difficulty in defining Quakerism is both a challenge and a gift; it opens doors to conversation and is therefore advantageous to this project. In its inherent doctrinal-agnostic ethos (jargon we do not use in the workshop or workbook), young adults from many different spiritual backgrounds (or no spiritual background) are welcomed into the fold. Many young adults have left their traditions or seek wisdom elsewhere as a result of theological harm (something both of us know too much about from personal experience). This lack of doctrine broadens the scope of who can benefit from a workshop or retreat grounded in Quaker practice.

In our workshop, however, our participants learn more about Quakerism through doing than through deep study. We do provide a simple Quaker framework, and we tailor it to what the audience needs. Most often, we spend some time speaking about a guiding quote from George Fox: “Let your lives preach.” He wrote this in an epistle that exhorted early Friends to live holy lives and not to hide their light, referring to Matthew 5:16. In more recent years, these words from Fox have been popularized as “Let your life speak,” thanks to the Quaker author Parker Palmer’s well-known book with the same title, published in 1999. Letting our lives speak, we highlight their concepts, applying them to whatever context a person is in. For example, we may talk about the term “preach” for audiences that are very familiar with the concept as well as to folks who bristle at the word. We speak to those feelings and try to help the audience hear our point in their own language.

And our point is this: the word “preach” is powerful. There are two main differences between the quote from Fox and the quote from Palmer. The first difference we talk about is the use of the plural. Fox uses the plural “lives” while Parker uses the singular “life.” When we let our lives speak/preach, we inspire others to let their lives speak/preach; it can be and is contagious. The second difference between the two is Fox’s use of “preach,” while Parker uses the word “speak.” Greg feels especially called to preach, and when he preaches, he talks about his deeply held beliefs. We ask the workshop participants: What would you want your life to say about your own deeply held beliefs? What would your life preach about what you hold so dear? This message resonates.

For the rest of the workshop, the Quaker pieces come alongside key activities for the participants. We help participants listen to their inner guide by having them respond to prompts for listening to themselves and naming their desires and strengths. We have folks talk about their experience of answering prompts, rather than the answers, to root that knowledge in their bodies. We have participants create a query (borrowing from an exercise developed by Callid Keefe-Perry of New England Yearly Meeting) for their time in the workshop, which can serve others by allowing them to participate in their discernment, which we define as thinking deeply about something in relation to what you hold most dear. This can allow each participant room to know there is not one right answer. Participants take part in a shortened form of a clearness committee, so each participant can go deeper in their discernment by being held in community—a process that they can use time and again as these questions of vocation surface.

The participants notice these gains and have shared feedback with us. For example, someone wrote, “It’s so refreshing to be in a space of uplifting and warm community. It’s easy to forget that these spaces exist, and it’s lovely and encouraging to remember goodwill among people and that we all share so many of the same questions.”

Another wrote:

I am taking away a renewed appreciation for awareness of and the ability to practice patience. In practices of sharing silence, asking the same question of my heart multiple times and listening to others, I was reminded just how slowly my own ideas and callings can shift and emerge. I’m taking away a direction to look and move as I approach future steps. I’m taking away any number of exercises, for myself and my spiritual companions, and a familiarity with new language and framing for being in these conversations with others.

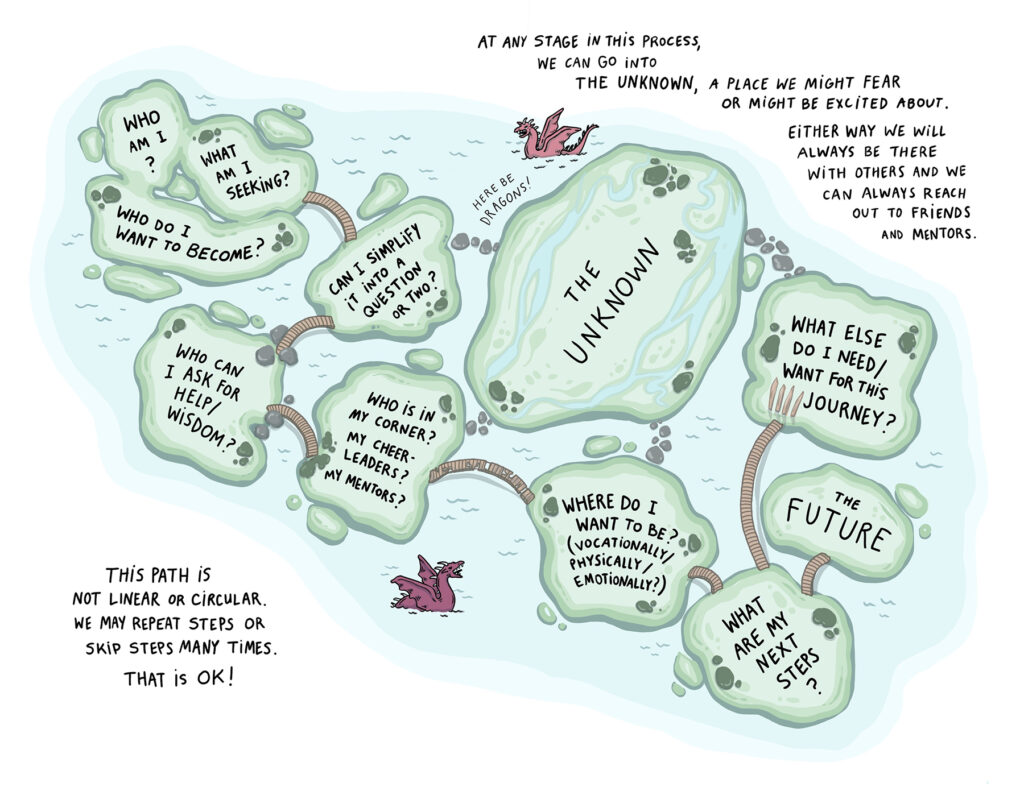

Vocational discernment is not always a linear path. Sometimes vocation feels like two steps forward and one step back, or even like a spiral. What works for one person does not work for another, and discernment is a lifelong process. God will continue to use and lead us in different ways throughout our lives. To teach these truths, we developed a non-linear or circular map of vocational discernment that Joey Hartmann-Dow made into a beautiful piece of art.

The map’s concept is that discernment is a series of islands that contain questions we can linger on for a while. There are bridges between the islands, including some that are precarious, which symbolizes the systemic and structural pitfalls that are a part of life and very much a part of the vocational journey. The biggest island on the map is not a question but “the Unknown,” because you never know where the journey will take you.

Close to the Unknown Island are the words: “Here Be Dragons.” Some early mapmakers would put these words on their maps of uncharted territory as a type of warning that there could be danger in these places. Yet for us, putting this label on the map was an invitation, because dragons are magical, mythical creatures. The unknown can be scary, yet at the same time, it can take us places that we could never imagine. This has happened to both of us in our lives. This map and the artwork throughout the book are not just concepts to think about but are visual aids to discernment that stick with you.

How do we see this as part of the framework for welcoming young people into Quakerism?

Each time we have run this workshop for young adults, participants have been curious about Quakerism. Our overall goal with these workshops is not necessarily to create new Quakers but to give people, especially young adults, tools to help them find their calling now and to discern future steps/callings. Our framework is Quaker because we are Friends, and these practices are what have been helpful in our own lives. However, through teaching Quaker principles and allowing time for young adults to try out Quaker practices, we are still spreading Quakerism to young adults and inspiring others to live out their calling.

Although we are specifically interested in vocational discernment, this is only a part of the bigger question of young adult engagement: What does Quakerism have to offer? How can Friends do that well by creating the containers and spaces that allow Quaker practices and principles to show—rather than tell—people the value of Quakerism? How can Friends invite people into the experience?

We believe that Quakerism has a lot to offer the world, especially young adults. We want to continue to offer opportunities for folks to experience the pieces of Quakerism that have been life-changing for us. Perhaps Friends can explore more offerings like ours to help folks experience what Quaker practice can do for their lives.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.