It started with a despairing text from a friend at the end of 2021. She had just read the website of a guy running in our district—unopposed—for the county board. His website was all about gun rights, jury nullification, and armed resistance to the government. What to do?

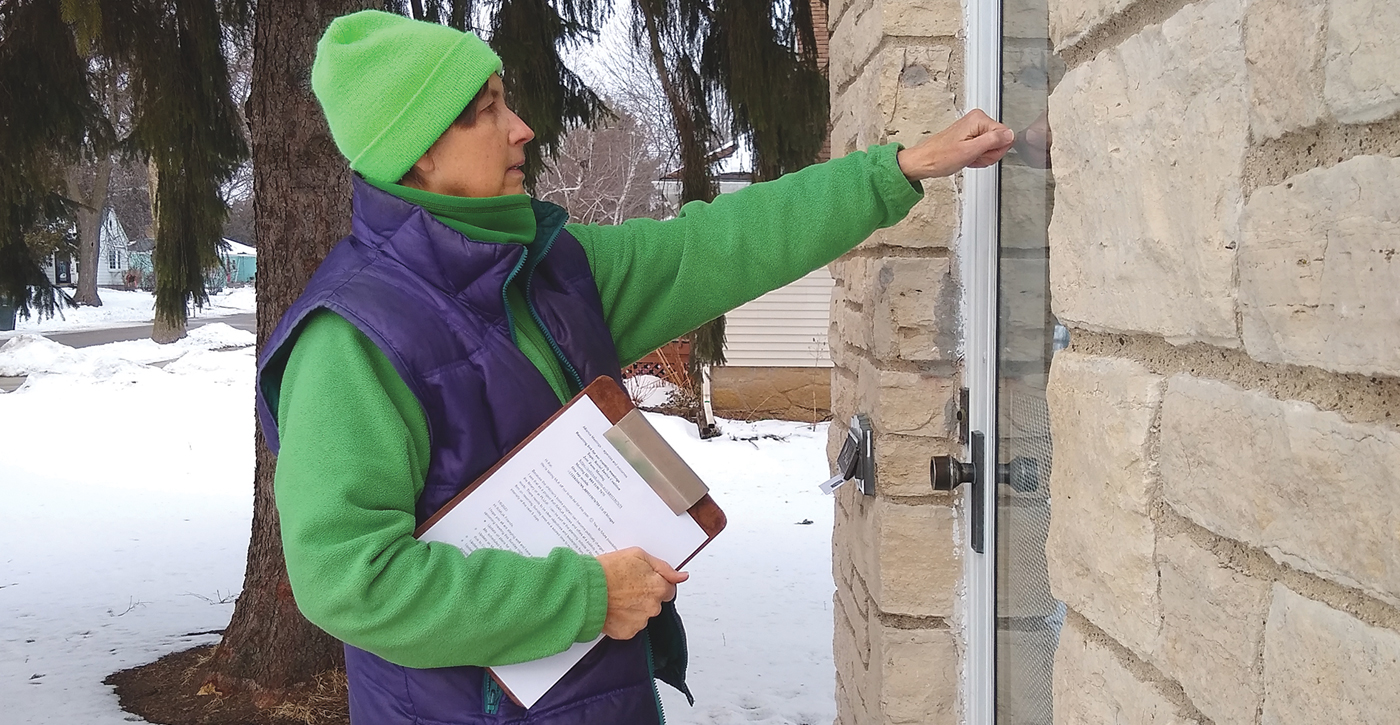

Over the next 24 hours, a thought found its way into my mind: Should I run? This improbable idea clung to me with a sort of static electricity; I couldn’t shake it. I asked my family to be a clearness committee for me, and within an hour, my husband was making a spreadsheet of contacts to reach out to, and my daughter offered to canvas for nomination signatures. On the last workday of the year, I picked up nomination papers to run.

At around 9:00 a.m. on New Year’s Day, in sub-zero weather, I knocked on the door of our former state senator, a rock-ribbed Republican, to ask for his signature. Understand: this was more than a little cheeky of me. Our last interaction had involved me demonstrating in his driveway against his support for Act 10, which gutted the teachers’ union and other public sector unions. But . . . he signed!

Lesson 1: Asking Republicans to support me gave me an unexpected chance to honor Republicans. The implicit message of my knocking on their doors was that I cared about what they thought, trusted our interactions had value, believed we had important things in common, and I considered at least some of our differences to be bridgeable.

Over the next couple of months, I went door-to-door throughout my small district of about 4,000, asking people what they thought about various county issues.

Surprise! It turned out I loved campaigning for a nonpartisan office! I had canvassed for the past 25 years for just about every Democratic sacrificial lamb running for anything in red east-central Wisconsin, but canvassing for myself, for a nonpartisan office, was totally different. First of all, I was talking to more Republicans and Independents than Democrats. Because I couldn’t assume agreement, I found myself talking less and listening more, feeling around for any common ground. Almost always, we found it. And then we would spin a conversation around that shared thing, and it would grow outward into a web of related explorations, and pretty soon there might be a whole bunch of things we could talk about. Most of my conversations lasted 20–30 minutes. Most of them were deeply satisfying.

Because I couldn’t assume agreement, I found myself talking less and listening more, feeling aroundfor any common ground. Almost always, we found it.

These conversations reminded me of a talk I once gave when I was a community organizer raising concerns about agricultural biotechnology. I had been invited to speak to a group I’d never heard of: the Beltline Optimists. I figured they must be some sort of diet club. I prepared a talk addressing the false promise of things like broccoli genetically engineered to taste like it already had cheese on it. (Yes, this was a thing, and this being Wisconsin, any vegetable not drowning in cheese was viewed with suspicion verging on alarm.) I got to the meeting, and was promptly served a large platter of steak and eggs for breakfast. Oops! This was not a diet club!

Who on earth were these people? I listened intently all through breakfast, read the Optimists’ Creed posted on the wall, and sounded out my table mates with an urgently interested flurry of questions. In the end, I threw out my prepared remarks and improvised a completely new presentation tailored to these good and earnest people. It was unexpectedly one of the best—or at least most rapturously received—talks I ever gave. (Okay, maybe optimists were easy to please.)

Lesson 2: The secret to having successful conversations across the aisle is to ditch my own agenda in favor of learning about theirs.

That’s what I did on doorstep after doorstep in my hometown of Ripon, and the conversations were as varied, surprising, and delightful as the world’s ideas on what constitutes a good breakfast. I came away from these canvassing shifts unexpectedly heartened. I even kind of fell in love with my community all over again!

But alas, it wasn’t all puppies and rainbows and chatting on front porches. Social media was . . . well . . . everything: powerful, dangerous, awful, delightful, compelling, and potentially a black hole for psychic energy. I was trolled repeatedly, and I also had a couple of “Facebook Angels” who responded with calm, kindness, and reason to a few particularly combustible souls.

While there were conflagrations I steered clear of, there were also individuals I reached out to personally, and surprisingly often these interactions went well. I offered to meet in person with a couple of serial trolls to hear them out, and a couple of them went silent after that. I also learned, less encouragingly, that some of my supporters were as intemperate as my trolls. The message I put out was: You will not love me better by hating my opponent. Please do not hate my opponent.

I invited my opponent to shake hands on camera and pledge our commitment to a positive campaign. We did, and posted the resulting picture on Facebook. It’s fair to say that in print, both of us mostly stuck to this.

But eventually I faced a difficult choice: whether to continue to focus exclusively on the positive reasons to vote for me for county board or whether to raise up some truths about my opponent. It was clear that many people felt pretty ho-hum about county affairs (in truth, so did I before I ran for office) and that the prospect of voting me into office was not electrifying. What was electrifying for moderate to progressive voters was finding out that my opponent was prepared to take up arms against the government and overrule juries, among other things.

Was the community well-served by a positive campaign that failed to address these issues?

I’m not sure I’ll ever have a fully satisfactory answer to that. I decided to express some of my concerns about my opponent’s positions, and have wondered ever since: was my decision to break my pledge a mistake, or was the pledge itself the mistake? Was the body politic better served by outing my opponent’s more extreme views (they were on his website, but surprisingly few people seemed to go there) or by sticking to a strictly positive campaign? Was there any “pure” action to take in these circumstances? Was purity even the right goal?

I do know this: there was a rabid Christian nationalist candidate who believed in executing gays; internet trolls making up outlandish stuff about me; an electorate that was by turns foaming at the mouth and apathetic; and me: scratching my head, praying, and not coming to clarity.

The closest I have come to clarity since then is that wading through this grubby situation was perhaps the price of getting involved in electoral politics.

Lesson 3: As English critic G. K. Chesterton once said: “Art, like morality, consists in drawing the line somewhere.” Where to draw it in these circumstances was murky, and experience so far tells me that I will have to live with such murkiness. I will not always have the luxury of certainty that I did the right thing. I also think that being unwilling to pay this price exacts a different price.

The campaign, as it turned out, was considerably less bewildering than my first months of being on the county board. I had expected a deliberative body weighing possible courses of action, discussing the ins and outs of various policies, and hashing out compromises. Hah! Meeting after meeting involved an agenda dominated by mysterious and often trivial-seeming resolutions, which the board voted for unanimously with no discussion. None of the things I ran on seemed even remotely attainable; they simply had nothing to do with the business that came before us.

My platform included resilience in the face of climate crises and other challenges, welcoming all kinds of people, and sustainability. But it seemed like as a board we spent more time honoring local winning teams and overseeing lease agreements for the county hangar space than dealing with crucial local policy issues. And the committee to which I was assigned virtually never gets to make a decision because almost all the work we oversee is mandated by the state or federal government. Not much room for policy innovation there!

Lesson 4: A campaign platform is an exercise in fantasy fiction!

I ran because I wanted to make county governance better, but I found a different toehold: raising up the good work already being done! In this divided and distrustful time, might that be the more important role? Giving people a reason to believe in local government at all seems like a mission all by itself.

A year into the job, here is what I have figured out to do: I poke around and ask a ton of questions. I interview everyone and her sister. I ride along with sheriff deputies and cops—and feel mildly embarrassed at how much I like driving 120 mph! I tour the highway department and try out the controls of a snowplow and learn the finer points of road salting. I tour the nursing home and jail. I interview my constituents who have dreadful broadband access or who are upset about an upcoming highway project, and I lobby for them.

I also go to finance committee meetings, even though I’m not on the finance committee. They’re the ones who get to decide everything, and if they can get away with it, they do it out of earshot of people like me. They look crestfallen every time I come in—like it would have been such a fun good old boys’ party if I hadn’t showed up! Sometimes I try to challenge them, and I get shut down or shot down. So I keep on trying to learn as much as I can in the hopes that someday I’ll be in the right place at the right time with the right information or idea to make a difference.

Perhaps most importantly, I write a monthly column on county affairs for our local paper. I spend a lot of column inches raising up the good work of county employees. Most of this work—fixing roads, collecting child support, running the county jail, maintaining parks, holding elections—is genuinely nonpartisan. It also impacts our lives at least as much as what passes for governance in Washington, D.C. When I got home from my highway department tour, I talked about it for weeks: the insanely complicated snowplow cockpits, and all the stuff other counties hire us to do for them. I’m genuinely proud of our long-term care facility, our parks, and our economic support team, and I talk about these things with anyone who will listen.

And to my surprise, people are listening! Everywhere I go, people ask me questions about the county government: at parties, over a beer, in the supermarket, at the gym . . . wherever. People seem interested and invested. They care. They smile with pride when I tell them good news.

I ran because I wanted to make county governance better, but I found a different toehold: raising up the good work already being done! In this divided and distrustful time, might that be the more important role? Giving people a reason to believe in local government at all seems like a mission all by itself. And it’s a way into something in short supply these days: a sense of “we-ness.” We have an award-winning long-term care facility. We have some fabulous bike trails. We have a county health department that won multiple awards for its COVID response.

What could be more important in 2023 than knitting a corner of angry, divided Wisconsin back together into we-ness?

I get really positive feedback on my monthly columns. People tell me all the time how much they like learning this stuff. Sometimes Republicans say nice things or stick up for me. The other day one texted me to say, “It is refreshing to read about our government in action without a political bias.” Another recently responded to someone’s comment about hoping I would run for higher office (not a chance!) with, “I like you too much to want you to go through the Democrat-shredder that is Wisconsin’s Sixth Congressional District!”

In this place and in this time, this feels like success enough.

This was my favorite paragraph in your article:

“Lesson 1: Asking Republicans to support me gave me an unexpected chance to honor Republicans. The implicit message of my knocking on their doors was that I cared about what they thought, trusted our interactions had value, believed we had important things in common, and I considered at least some of our differences to be bridgeable.”

As a conservative Independent voter, I have given up any hope of fairness and understanding from Democrats. Your words gave me a small spark of hope, but I remain cynical. We now live in an era in which our Department of Justice fiercely pursues parents, pro-life activists and Donald Trump, yet ignores the activities of Hillary Clinton and the Bidens. Maybe someday we will all live in a better world.

Many thanks.

Thank you for this article. I’m based in Toowoomba, Australia and I will be running for local government next year. If I succeed, I’ll be one of the only quakers to hold office ever in Australia