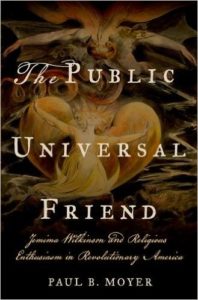

The Public Universal Friend: Jemima Wilkinson and Religious Enthusiasm in Revolutionary America

Reviewed by Paul Buckley

June 1, 2016

By Paul B. Moyer. Cornell University Press, 2015. 272 pages. $27.95/hardcover; $24.95/eBook.

By Paul B. Moyer. Cornell University Press, 2015. 272 pages. $27.95/hardcover; $24.95/eBook.

Buy on QuakerBooks

On November 29, 1752, a daughter was born to Jeremiah and Amey Wilkinson, a Quaker couple living in Rhode Island. They named her Jemima. Almost 24 years later, unmarried and still living at home, she fell ill, and over the next week, she steadily weakened. On October 11, 1776, she was reported to have died. According to accounts published later, her soul left her body and was taken up to heaven. At the same time, God reanimated her corpse to become the earthly vessel of a divine spirit who announced his name was the Public Universal Friend. You may not have noticed the gender change of the pronoun in the previous sentence—it was intentional. As a spirit, the Public Universal Friend was neither male nor female, but he insisted that his embodied form be addressed as male.

Paul Moyer has documented the subsequent life and ministry of the Public Universal Friend, who founded a new religious society, the Society of Universal Friends, and traveled in the ministry to gain new followers. Like several other new religious bodies in the post-Revolutionary War United States, he established a separate religious community on the frontier, and, like nearly every other such utopian society of those years, it failed to survive for long after the death of its founder.

If that was all this book revealed, I wouldn’t advise Friends to read it. But there is something more embedded in this text that we need to see and acknowledge. Quaker mythology revels in the deep roots of equality within the Religious Society of Friends. We rightly celebrate the fact that Quakers rid themselves of involvement in slavery long before other denominations, but it is only recently that we have also recognized that our spiritual ancestors were not also able to scrub out the racism so prevalent in the surrounding culture. Books like Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship by Donna McDaniel and Vanessa Julye have forced us to confront the limits of racial equality among Friends.

Reading The Public Universal Friend may help us to come to a similar understanding of how women were treated in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—by the wider society and more especially by our religious society. All too often, Moyer points out how possession of a female body interfered with work of God’s Messenger in the world. Worse for us, some of the most pointedly gendered criticism came from prominent male Quakers. It was one thing to proudly assert spiritual equality and defend a woman’s right to minister, but quite another to acquiesce to a woman owning property in her own name or being in a position of authority over men.

This is not to denigrate nineteenth-century Quakers for being people of their times. They were ahead of others and we should remember those achievements. But just as we have faced up to our past racial shortcomings, we need to see clearly the station assigned to women 200 years ago. This book provides a window into our past. If we are to know where we come from, we need to peer through it.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.